The artist’s current exhibition at Sfeir-Semler Downtown, entitled Stray Salt, examines the manipulation and politicisation of mythology through a contemporary lens.

Continuing on from her exhibition representing Lebanon at Venice Art Biennale 2024, Mounira Al Solh returns home with a new show. This exhibition marks the second chapter in the artist’s ongoing investigation into the construction of national narratives and the reappropriation of mythology, told through a female-centric perspective that unfolds across sculpture, film, paintings and textile works.

The project delves into how these historical myths – often reinterpreted or borrowed by Greco-Roman society to fit a more Western-centric narrative – still hold relevance to contemporary society, often traversing war, catastrophe, misogyny and migration.

While her Venice show explored the myth of Phoenician Princess Europa’s abduction from the shores of Tyre in south Lebanon, Stray Salt unpacks the journey of Queen Dido of Tyre (also known as Elissa), who fled her tyrannical brother and founded the Phoenician city of Carthage in modern-day Tunisia. A few new artworks continue the story of Europa, drawing comparisons between the stories of both women.

Al Solh begins by looking at the story of 80 women who fled with Dido, and through advantageous marriages expanded her clan and populated Carthage, creating a new city. Western historical myths and stories label these women distastefully, but Al Solh offers a more nuanced reading of events. “In the exhibition, you will see colourful paintings of what I call ‘Elissa’s Girls,’” she tells Canvas. “Western history labelled them as prostitutes and wrote a biased history about Phoenicians. They accused them of sacrificing women, children and animals, due to the discovery of jars filled with bones, but it was never really proven. It was simply known that many at that time practiced sacrifice to please the gods.”

“Some historians even pretended Phoenicians didn’t exist, and if they did, they deemed them unworthy to write about since they sacrificed children,” she adds. “They would say, for example, that they sacrificed their women in specific rituals, offering them as prostitutes who had to please men. In my paintings, those accused women take back their will playfully.”

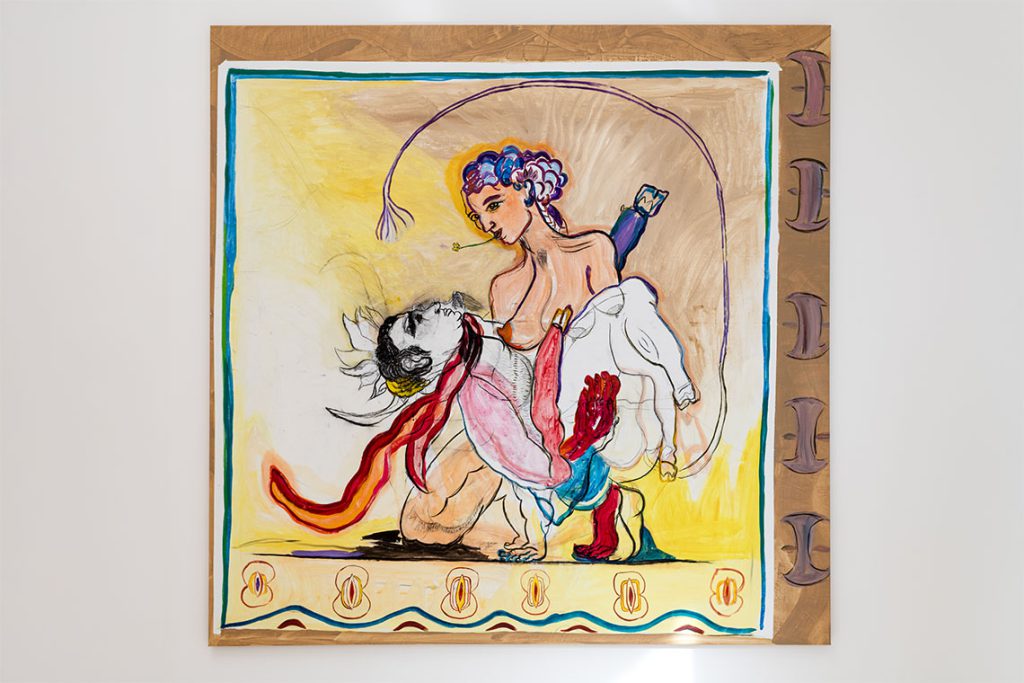

The paintings celebrate the female figure and women as the givers of all life, styled somewhere between Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus and Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde. The paintings attempt to reframe the role of women through the centuries as the fundamental catalysts that purposely enacted great changes, rather than passive figures that events simply ‘happened’ to, in turn allowing these sweeping stories and myths to unfold.

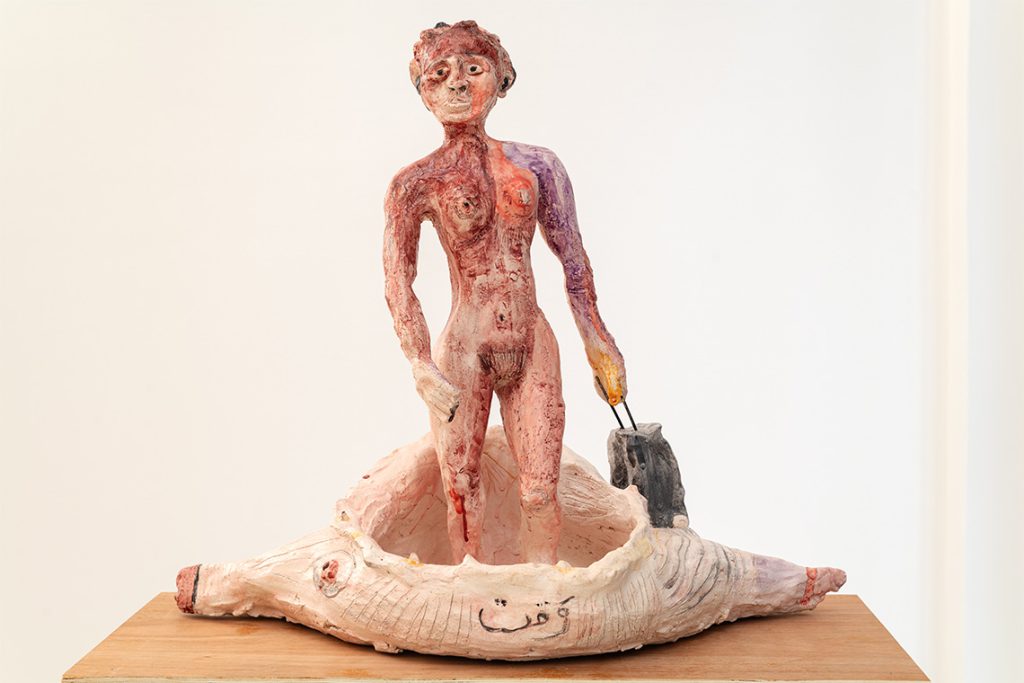

Also echoing Venus emerging from her seashell is the glazed ceramic sculpture Intemporal (2025), which responds to the Lebanese Emigrant Statue, created in Mexico in late 1979 by Ramis Barquet. Numerous replicas have since been placed worldwide, including a monumental version installed at Beirut’s port in 2003. The original statue by Barquet was commissioned to honour the Lebanese emigrants who fled the 1975–90 Civil War and earlier hardships, seeking peace and prosperity on other shores and in turn creating entire subcultures that thrived, boosted local economies and brought new skills with them.

Al Solh’s sculpture gazes at the viewer from the gallery’s window front, this time depicting a nude female traveller instead of a traditionally garbed male figure, standing in a shell-like boat named ‘Waqt’ (‘time’ in Arabic) and trailing a modern suitcase behind her in a celebration of women emigrants across history who have helped build entire communities.

Image courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery Beirut/Hamburg

Despite exploring different topics, the artworks are all threaded with motifs found on antique mosaics, bas-reliefs or Phoenician lettering with depictions of boats or female figures, all the while keeping to an earthy colour palette derived from the natural pigments and hues used by the Phoenicians.

In one of the larger works on canvas, When the Season of Sorrel Comes (2025), the artist combines yellow natural pigments and Phoenician red to reimagine Europa. Instead of being abducted by Zeus, here the princess cradles the half-human-half-bull god in a stance that negates the ‘damsel in distress’ narrative.

In the centre of the gallery space, a wooden fishing boat nods to Lebanon’s ancestral links to the sea: a source of sustenance, of economic boon and a passageway all at once. It carries a flat TV screen with Al Solh’s newest video work, Two Airplanes and the Luggage (2025), in which an animated cartoon video shows Europa fleeing over the water, abandoning her suitcase and the bull – an intrinsic part of her story – to escape bombings. Al Solh whistles, hums and buzzes the score herself, mimicking birds chirping, war planes and explosions.

“[The wooden boat] is a symbolic representation of Elissa’s exile journey to Tunis,” she explains. “It creates a parallelism with the story of the Lebanese people, especially after the port blast in 2020. I remember seeing people all over the streets trying to find a shelter, a place to escape to.”

Nearby sits The Pyramid of Heads (2025), a textile painting that looks at the story of the Assyrian King Salmanazar III, who was known for his cruelty, piling up heads of rebellious citizens in the shape of a pyramid. The Phoenicians, and other states in the region, were plagued by his invasions.

“Phoenicians had to pay many tributes to the powerful and changing ruling empires in the region; not only the Assyrians, to whom they had paid tribute in everything from cedar wood and olive oil to textiles and the like,” Al Solh says. “The Pyramid of Heads was painted when the Israeli war was raging on our region and on Lebanon. I could not distinguish anymore between the old past and what was happening at present in our region. The inclusion of the Baalbek Temple pillars – the largest Roman Heliopolis in the world – warns about our currently endangered heritage sites that are not depoliticised when conflicts arise.”

Other smaller works make up the rest of the exhibition, such as four hand-embroidered cedar cones – representing a rare species of Lebanese cedar, in which both male and female parts are present in a single tree, making it reproductively independent. Ceramic masks, tied to rituals and painted with crying faces, and a set of embroidered red sea shells, echo the paintings of Dido’s girls. In the coming months, Al Solh plans to create a film about the story of Dido, to be filmed in various ancient sites connected to the tale, similar to the one she created about Europa.

Other chapters, also rethinking the myths of Phoenician women, are in the work. In Stray Salt, Al Solh continues to highlight moments of violent rupture, from ancient myths to current tragedies and conflicts, connecting past and present through themes of exile, loss and injustice that are keenly relevant to our troubled times.