Unceasingly questioning and analytical, the artist leaves no stone unturned in his search for a real sense of truth and reality.

Wael Shawky doesn’t trust history. In fact, he has said he doesn’t believe in it. His work, spanning film, painting and sculpture, is known for dissecting not so much the documentation of history but its narrative fabrications, the interlacing of myth and fact in stories woven by nation states and those with power and influence. “I always say that my fascination is in analysing societies in transition,” he says. He ascribes this interest to his childhood in Mecca during Saudi Arabia’s 1970s oil boom. Although he was born in Alexandria, he spent his younger years flitting between Egypt and Saudi, where he witnessed the seismic shift in the latter’s economy and society. “This was the time of the Bedouin man driving a Cadillac,” he recalls.

I caught up with the artist as he was triangulating the cities of Alexandria (where he is working in his studio on post-production for a new film, I Am Hymns of the New Temples, 2023), Jeddah (for his participation in the first Islamic Arts Biennale), and Dubai (a transit hub he sometimes visits with family and where we meet). The artist recalls Mecca as “rough, even sometimes aggressive”, where a tribal culture at times chafed against the “new capitalism of America”. In parallel, the holy city was uniquely cosmopolitan, with pilgrims from around the world gathering, many setting down roots illegally. Putting his drawing skills to use at a young age, Shawky became the go-to artist as a student: “I think I was responsible for all the drawings at the school. This is weird, but it’s real – as a kid, I thought all Egyptians knew how to draw. Because I was the only Egyptian in school!” he laughs. He returned to Alexandria as a teenager, a “terrible phase”, as he puts it, filled with “crazy, stupid fun” that almost derailed his artistic career path. Eventually, with a push from his mother, he enrolled into the fine arts programme at Alexandria University and never looked back. Trained as a painter, he ventured into film while pursuing his MFA at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, where he has another studio.

Shawky’s works have been exhibited at the KW Institute, Serpentine Galleries, Tate Modern, MoMA PS1, Sharjah Art Foundation, Mathaf, M Leuven and Castello di Rivoli, among others. He has also participated in the Venice Biennale, Sharjah Biennial, documenta, Istanbul Biennial and Desert X AlUla. Across his practice, he scrutinises what he calls the “dream of development” that he sees as pervasive in societies. “It is a dream to be higher, in money, in social class, and even in going to heaven. We all experience it. It’s not greed. It’s desire.” This dream or desire becomes the driving force for war and expansion, for transformations from nomadic and agrarian societies to industrial and urban ones. At the same time, the artist questions how conflict and change are remembered and retold, embedded in memories and identities.

His much-lauded film trilogy Cabaret Crusades (2010–15) demonstrates this varyingly – first from a matter of perspective, recounting the medieval religious conquests in the Middle East from the Arab side, then warped by representation, with marionettes as actors reciting lines in classical Arabic, at times accompanied by Bahraini sea songs. With each film, the characters become more zoomorphic, starting with 200-year-old marionettes from the Lupi family collection in Turin, then ceramic ones made by French craftsmen, and in the final film, murano glass marionettes with creature-like faces. Shawky spent five years gathering maps and reading various texts to develop the films, as well as producing the ‘actors’ and accompanying music.

Often, the marionettes are displayed alongside the films behind a glass display, where they stand mute and stripped of their personalities on screen. Shawky sees this as the “truth”, a reminder that narrative is constructed and directed by the human hand.

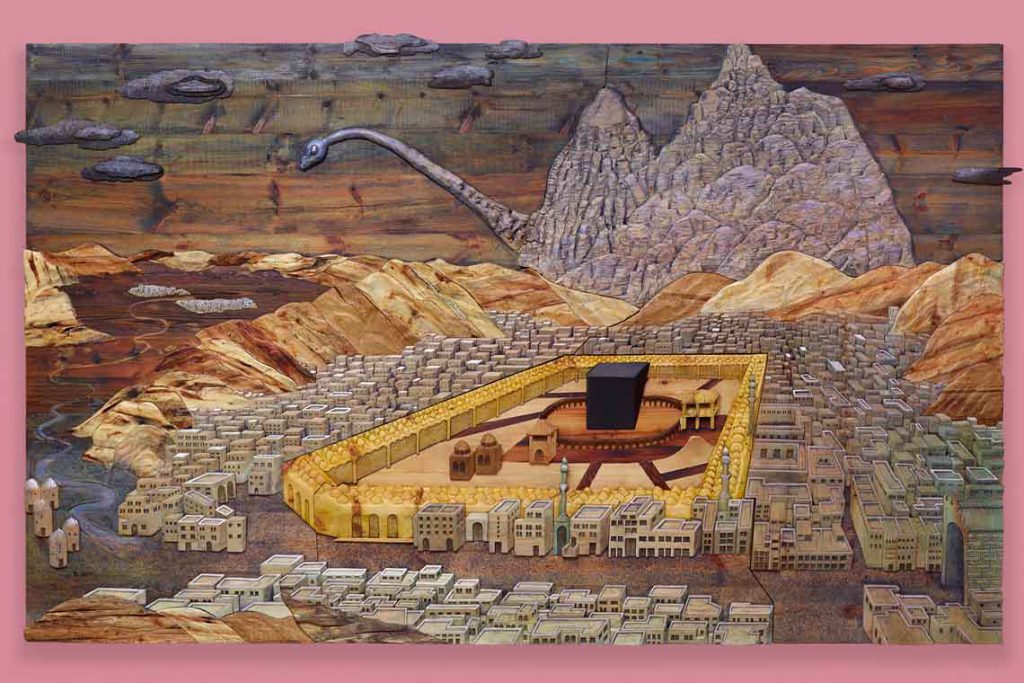

For The Gulf Project Camp, shown at the Lisson Gallery in New York in 2019, Shawky filled the space with bas reliefs and drawings, as well as a crenellated structure and sculptures in the centre. True to Shawky’s themes, the works reflect on the development of the Gulf region from the 17th century, with a focus on the landscape of Mecca, for which the artist researched old maps, miniatures and panoramic drawings. Historical accuracy is replaced by fantasy as Shawky inserts his distinctive hybrid monsters into the scenes. Particularly striking, the reliefs highlight the rugged terrain of Mecca’s surrounding mountains which, in the present day, are now covered by buildings. One work entitled The Gulf Project Camp: Carved wood (after ‘Hajj (Panoramic Overview of Mecca)’ by Andreas Magnus Hunglinger, 1803) (2019) renders the Kaaba and its setting empty except for a lone dinosaur looming over the city in what could be a predatory or protective stance. In one sculptural piece, a prehistoric creature slovenly carries the Al Haram Mosque complex on its back, evoking the common fiction of crude oil coming from dead dinosaurs.

Such beasts have become a part of Shawky’s visual language, although the artist cannot pinpoint their exact origins or inspirations. “It’s difficult for me to understand where they come from, but I’m sure they have a source,” he says, adding that he sees elements of influence from the painters he admired as a student, such as Francis Bacon, Joseph Beuys, and towards the more abstract, Gotthard Graubner and Gerhard Richter. His current show with Lisson in New York, entitled Isles of the Blessed (ended 13 January), marks the artist’s return to painting. Produced in his Philadelphia studio, 11 new works feature Shawky’s strange beings – long-necked, beaked, thick drooped lashes, and with multiple limbs, fingers and toes, they are at once human, avian, reptilian, odd, charming, prehistoric and anachronistic. Painted in strong, luminous colours, their skins dappled with the artist’s characteristic daubs and strokes, his subjects trek through mountains and traverse seas.

For this series, the artist has ventured into Greek myth. The paintings are accompanied by a short video with a clay marionette who narrates the story of Europa, a Phoenician princess whose kidnapping by Zeus instigates a search led by her brother Cadmus. Instead of finding Europa, however, Cadmus’s path turns toward one of self-interest. After an oracle tells Cadmus to “forget about Europe”, he goes on to establish his own city of Thebes and cements his empire. In the end, he makes it to the Isles of the Blessed, a paradise for heroes of Greek mythology. Europa, on the other hand, never resurfaces. Shawky finds this twist of events amusing, as hinted in the title of the video Isles of the Blessed (Oops! … I Forgot Europe) (2022), but the draw of the story relates once again to notions of power, development, history and truth. “There’s something very politically interesting here,” he says. “It reminds me of an authority or a leader who is leading his own main mission to build his own legacy yet claims to his people that God directed him to do this. It’s God, not his ego.” It’s a clever parallel, and evident in many leaders of today, particularly those in regions where development and progress is the main mission. Who are all the new projects really for? And how does power build its own mythology? The artist adds with levity: “[The leader] continues to do something different and he still goes to heaven. So it’s like, he forgot about you.”

Isles of the Blessed was first shown in Brussels and sprung out of a larger project that Shawky is currently finalising, a feature shot in the ruins of the ancient city of Pompeii called I Am Hymns of the New Temples. He stumbled on the story of Europa during his research on creation myths. “The story is about the creation of the universe. Starting from nothingness, from silence, then to the creation of Chronos, then Zeus, then human beings… This was created before all the religions and you see reflections of all these stories in Islam, Christianity, Judaism.” As far as Shawky is concerned, we have been telling ourselves the same stories across millennia, but who is to say that any of them are the singular truth? When it comes to medieval history and the Crusades, for example, the surrounding accounts were as much imbued with myths as with facts. Shawky offers Charlemagne and his sword as an example. “Suddenly, one day, it was considered real history,” he says. The film will premiere in Pompeii in February, after which it will travel to Milan. Shawky’s 2023 calendar is already full, with upcoming shows in Daegu, Lille and Beirut throughout the year.

His presentation at the Islamic Arts Biennale in Jeddah returns to a childhood memory, when he and his father spent the night in the open area of Muzdalifah, collecting stones along with countless other pilgrims as part of a ritual during Hajj. “I remember the sound of locusts and the light from this light pole. That’s it,” he recalls. His installation at the biennial attempts to recapture the contrast between the streetlight, a symbol of industry, and the buzz of locusts, a sound rooted in nature and religious undertones. It’s a typically skilled synthesis by an artist who excels at fusing craft and storytelling with a visionary take on contemporary life.

This profile first appeared in Canvas 106: Making their Mark