The artist taps into his own inner child to reveal the hopes and dreams of those who society has forgotten, providing us with a profound yet accessible framework for empathising with political and social issues.

Canvas: How did your interest in figure painting begin?

Walid Ardhaoui: It started with seeing footage of unemployed young people from poorer neighbourhoods across the world. They always seem to be out on the streets, some of them consuming drugs or alcohol. They are not bad people, but they are certainly victims of their situations, whether financial or cultural. Many are also honest dreamers, but their dreams are very naïve, almost childlike. To them, immigrating to Italy is heaven, or France is a place to make a lot of money. They don’t realise there is also unemployment and hardship in these countries. Their dreams are based on what they see online or on TV. Beautiful women and nice cars.

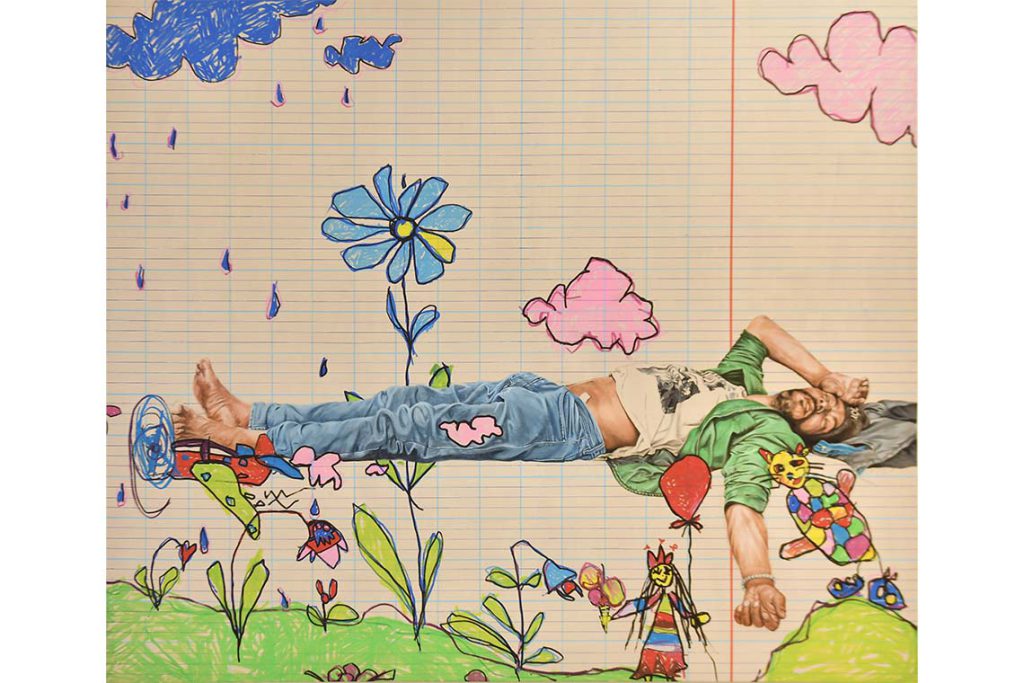

Your portraits are almost hyperrealistic but balanced by these seemingly spontaneous, youthful sketches. What is the significance of this juxtaposition?

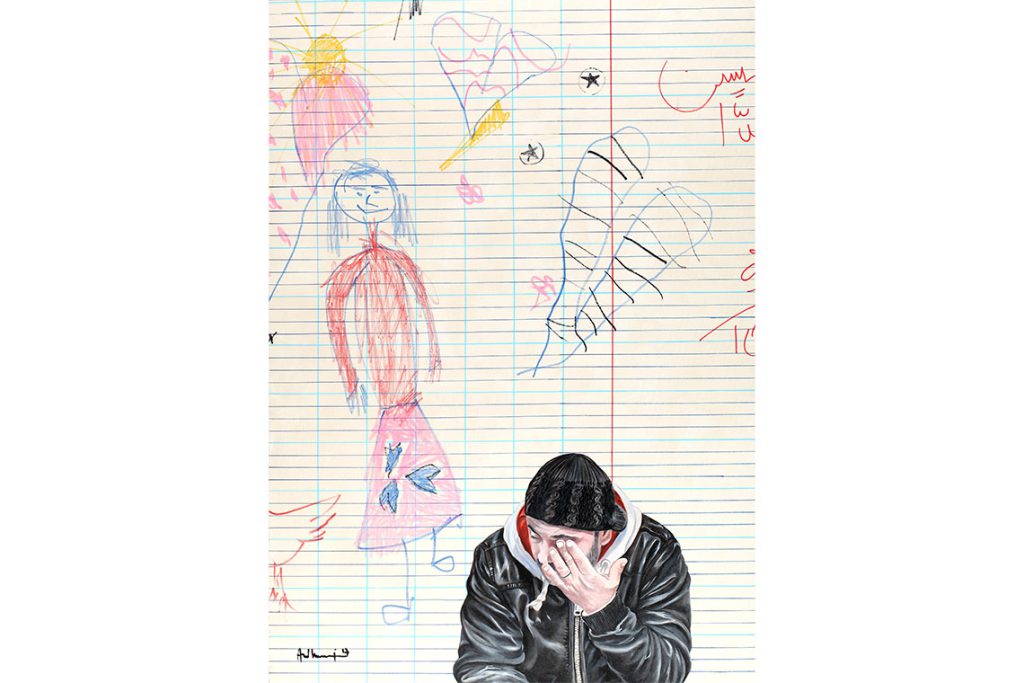

I want to depict two worlds, the innocent and the realistic. These spheres are very closely related, like love and hate or life and death. I aim to communicate the threshold between them and achieve a certain harmony. In terms of the actual portraits, I use oil paint to try to get into the details, such as the wounds on faces or hands. The time and concentration required to do this very precise work is a form of therapy for me. I also want to paint young people, who might be in despair, with a glimpse of hope and colour. They were once children with dreams.

How important is the dimension of dreaming in your work?

During my artist residencies in Senegal, Morocco, Tunisia and China, I found that all children dream the same way. Their imaginative, youthful freedom is a source of inspiration to me. Sometimes, I will work from scenes they have drawn for me, or I’ll even give them the canvas. There is something liberating in drawing the way a child would with acrylic paint, without the constraints of colour, volume, light and composition. It brings a lighter feeling to the work.

Are there certain themes that recur in your work, and do you ever draw on your own experiences?

My work highlights people who are often forgotten, such as the unemployed, the homeless, travelling salesmen and shepherds. For example, I painted a homeless friend of mine in Morocco. When he saw his portrait at the exhibition opening, he cried. He had never seen himself as important enough to be the subject of a painting. He felt he had no worth and didn’t realise that there was a certain beauty about him. I work primarily with this type of person. I try to render them realistically, but innocently, with some sadness.

One of your paintings, Isthme (2017), depicts a man sitting down, hunched over, rubbing his eye. There is a certain weight upon his shoulders and we can really feel the emotion. What was his story?

The man in that painting was about 25 years old and I got his photo from a journalist friend. He had just arrived in Italy after arriving illegally, exhausted and not knowing what to do. It was a new world to him. He had travelled for three days by sea and had even seen death on the way. He had managed to arrive at his destination, while others had been caught and deported.

What role does scale play with these portraits contrasted with the more intimate notebook drawings?

The portraits are life-sized, which makes them more real to people. The canvases can sometimes be as large as three metres. For the drawings, it’s as if the paper has grown with me. When you give a piece of A3 paper to a child, it’s almost half their height, so I replicate this scale as an adult. I also use bigger pens and try to draw with my left hand instead of my right. Sometimes, I don’t even look at the canvas when drawing, because this ability to render things as an artist can also hinder the freedom of expression. I even try to hold the pen like a child would, with my whole hand.

Artists often retain a childlike sense of wonder. Do you feel this quality in your work?

I struggled as a child with the constraints imposed by lines in notebooks, the lack of freedom and arbitrary punishment for not following them. I desired to attack the paper, because we were disciplined if we went outside the red margin line. Now, I am finding a pretext to attack the notebook because it was a crime to do so when I was young. My drawings are a rebellion against laws and against lines that almost represent a prison to me. I find it frustrating when a child is innocent and free but constrained by such rules.

Do you feel there is a tension between these two versions of yourself as an artist, the one who renders accurate details and the one trying to find this lost freedom?

The innocent part is especially challenging to find again. Picasso said he would spend the rest of his life trying to draw like a child again. Now I finally understand what he meant, because it’s very difficult to be naïve in your artwork. An artist always thinks about drawing accurately, even when trying not to do so. This is why I sometimes ask children to draw things for me. I find it inspiring because they don’t have any preconceived compositions. They know how to dream and they dream better than us.

When children draw, they are drawing not only their dreams but also their hopes, wishes and even fears. What do you think of when you create these drawings, and is there a part of yourself in them?

I try to imagine the dreams of those people I’ve painted. It’s as if I put myself in their shoes as a child. Sometimes it’s my dream, sometimes it’s my despair, but unconsciously there is always a part of me in it. I say these works are the dreams of the children, but maybe they are also my dreams.

This interview first appeared in Canvas 114: Once Upon A Time