From the ashes of the empires that have left their mark on the seaside town of Bonifacio, the straightforward yet effective biennale De Renava emerges.

In a small room cocooned in an archway over an alley in the Corsican clifftop town of Bonifacio, Napoleon Bonaparte – Emperor of France – once laid his hat. This summer and autumn, just a few hundred metres away in an abandoned 18th-century barracks, the International Contemporary Art Biennale of Bonifacio and the Alta Roca – De Renava, addresses the predictable fate of Napoleon and his ilk – a sequence of revolution, decadence and collapse – in its second edition, Roma Amor: The Fall of Empires.

Founded in 2020 by two Corsican friends, art historian Prisca Meslier and financier Dumè Marcellesi, De Renava aims to a create a “dialogue between artworks, architecture and nature” while simultaneously offering “alternative visions of [Corsica], its Mediterranean home and tomorrow’s world.”In a fortress city taken by the Pisans and the Genoese, the biennale’s organisers project the past onto the present and the future in an examination of the inevitability of imperial decline, from Roman times to contemporary instances, highlighting what the curators describe as “the paradoxical nature of History’s fateful march.”

The title, Roma Amor, is a palindrome and, fittingly, the exhibition can be viewed from beginning to end, or in reverse: the idea is that all empires sit somewhere on this timeline, that the writing is on the wall whichever way you walk. The exhibition equally suggests that everything – and nothing – changes.

With 18 works dotted about Bonifacio’s medieval citadel, the aim – one largely achieved – is to reactivate the architectural gems within the city: deconsecrated chapels and derelict nightclubs are transformed into temporary galleries for installations of varying kinds. The result is revelatory, both in terms of the buildings and the artworks.

Perhaps the most effective of these interactions is a screening of Bill Viola’s celebrated video and sound installation Tristan’s Ascension (The Sound of a Mountain Under a Waterfall) (2005) – depicting the figure of a man rising into a deluge of water – in the cool echo chamber of one of Bonifacio’s largest cisterns, into which the city’s rainfall once funnelled and which lies hidden away underneath a 12th-century church.

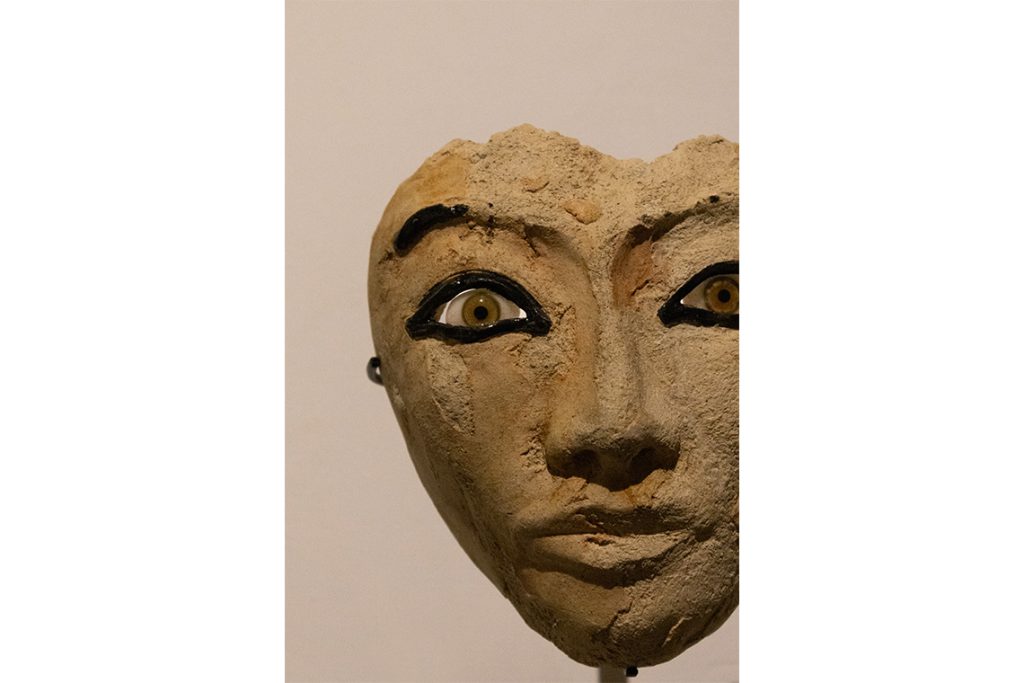

Alongside works by celebrated international figures such as Viola and Jean-Michel Basquiat, the curatorial team presents pieces by an impressive group of Middle Eastern figures. These range from grafted unions of cultural artifacts, such as busts and skulls, by the Lebanese artist Ali Cherri – providing a surreal commentary on political violence – to a bell forged from munitions spilt during the Iran-Iraq and the Gulf wars, a mournful creation by Kurdish-Iraqi conceptualist Hiwa K.

The exhibition is particularly strong on video works, never an easy medium to stage or engage the general public in. Here it works surprisingly well, not least because the spaces provide an atmospheric framework for the screens. Qatari-American artist, writer and filmmaker Sophia Al-Maria collages moonwalks, cave paintings and dystopian pop culture in her two-part video The Future was Desert (2016). As a reference point, she employs the Sumerian proverb “Mankind’s days are numbered, all their activities will be nothing but wind”. Meanwhile, down the corridor, shown in rooms wreathed in peeling wallpaper from the 1960s, Youssef Nabil’s short film I Saved My Belly Dancer (2015), featuring Salma Hayek and Tahar Rahim, churns up feelings of nostalgia for an artform out of favour with modern mores.

The most affecting of the video works is The Fury (2023) by Shirin Neshat. Two screens on facing walls play out two views of the same scene: one is of a woman in her underwear, dancing under duress in the grimy arena of a warehouse; the other is of her audience, Iranian soldiers who leer through their cigarette smoke. Viewed in a former military building, the film is profoundly unnerving.

Opposite the main exhibition in the old French building is a beautifully derelict 18th-century Genoese barracks and on the other side of that, perched on the cliff looking over the strait to Sardinia, sits a wooden pavilion built for the inaugural biennale (and which is now hosting a film installation focused on the “shadows of Corsica’s industrial past” by Ventiseri-based artist Valérie Giovanni). De Renava is interested in bringing new growth to the weeds of bygone days.

Dilapidated grandeur has a certain caché, of course. It’s immediately Instagram-able, but such sites have also always played into a heroic narrative. “We always need to find meaning in everything,” says Basile Isitt, the biennale’s director, adding that even the power brokers of Pompeii used ruins to “link themselves with prophesies and mythologies”. The artworks on view in Bonifacio deliver the iconography of decline and fall, but it’s a warped form of archaeology: the Corinthian columns are made of linen and cracked statues lean against graffiti or sit half-buried in stairwells.

Supporting this edition is an imaginative programme of events– guest speakers include novelist Jérôme Ferrari, winner of the Prix Goncourt – in addition to collaborations with Centre Pompidou in Paris and the Palais Fesch in Ajaccio. The resulting biennale is a triumph, both in conception and execution, accessible in its thematic approach and consistent in the quality of the works on view. It shows that ruins can make fine foundations.