The Weight of Words at the Henry Moore Institute proposes the potential of both the physical and symbolic weight of language, as sculpture and poetry overlap.

Parviz Tanavoli’s Standing Heech (2007) — ‘heech’ meaning ‘nothing’ in Farsi – reads as part Persian calligraphic script, and part an abstracted figure pulling away or preparing to pounce forward. It is one of many versions of the Iranian artist’s ‘heech’ motifs, which he has been producing since the 1960s, this one a curl of green fibreglass. It encapsulates how calligraphy is fundamental to Islamic art and a vital expression of the potential of words to not only be part of a sculpture, but to themselves have sculptural form.

Co-curated by Dr Clare O’Dowd, research curator at the Henry Moore Institute, and Nick Thurston, associate professor of fine art at the University of Leeds, The Weight of Words focuses on contemporary examples of the longstanding links between language and materiality. It features work by Caroline Bergvall with Ciarán Ó Meachair, Pavel Büchler, Anthony (Vahni) Capildeo, Tim Etchells, Simone Fattal with Etel Adnan, Shilpa Gupta, Emma Hart, Leslie Hewitt, Bhanu Kapil, Issam Kourbaj, Glenn Ligon, Mark Manders, Joo Yeon Park, Doris Salcedo, Shanzhai Lyric, Slavs and Tatars and Parviz Tanavoli.

The works on show speak in various tones, forms and degrees of translation, in direct abstract and metaphorical expressions that both reach out to their audience and refuse capture. Slavs and Tatars’s Szpagat (2017) — meaning ‘split’ in Polish, a split tongue, a body doing the splits, a banana split — “celebrates and upsets the ideal of a ‘mother tongue’ or native language as something singular and homogenising”, according to the exhibition literature. The Berlin-based collective poses a challenge to singular readings of all kinds, and the potential of extending in opposing directions.

Szpagat is a sculpture that evokes multiple readings, a sort-of object poetry. Shilpa Gupta’s Words Come from Ears (2018), a station motion flap-board displaying “unstable poetry” rather than information on arrivals and departures, speaks to the experience of being constantly in flux — the board itself ‘speaking’ through the soundscape of its mechanism as it shifts between words and meanings. Shanzhai Lyric’s Incomplete Poem (hedge) (2023) is an edit from an ongoing archive of ‘shanzhai’ garments — ‘shanzhai’ being a Chinese neologism for bootleg products — collected by the New York-based “poetic research and archival unit” founded by Ming Lin and Alexandra Tatarsky.

The archive celebrates the lyrical potential of bootlegging and the experimental English, consisting of modifications and mistranslations, that has developed in response to late capitalism; each piece in Incomplete Poem (hedge) is a poem in and of itself, and read as a collective entity its linguistic disobedience and melodic voice grows to a playful crescendo. The garments are hung on a wooden frame, which juts out into the space, delineating a barrier and route through, and built to the height of a standard British hedge. The hedge acts as a further linguistic device, communicating the nature of the division of common land, the hedge fund investment model, “property, proper-ness, global capital, hierarchies… and disobedient Englishes”.

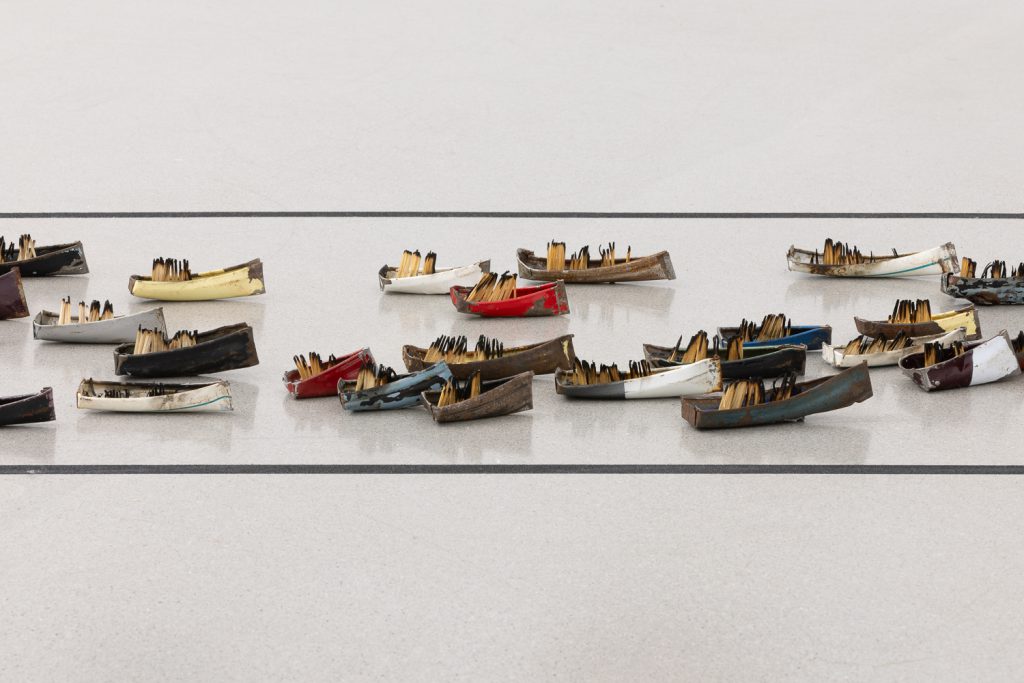

Issam Kourbaj’s Dark Water, Burning World 148 moons and counting… (2016) speaks through the symbolism of 148 boats — which will be added to every month — representing the number of months passed since the Syrian uprising that sparked civil war in 2011. The installation is part of a creative exchange with poet Ruth Padel, and Kourbaj’s boats, made from cut and folded bicycle mudguards and with burnt matches set upright in clear resin, extend across the floor of the gallery in a fleet, frozen on their journey towards the wall, constantly surveyed by the CCTV camera. The tiny scale of each boat, and their vulnerable position in the space, establishes the installation as an “anti-monument to the scale and tragedy of the refugee crisis”.

Artist and poet Etel Adnan worked from a position of exile, having first left Lebanon at the age of 24, living in France and America, and returning to Beirut as “an exile from an exile” throughout her life. In The Weight of Words, Adnan collaborates with sculptor, editor and her long-term partner, Simone Fattal, as Fattal “re-inscribes” Adnan’s 1969 poem Five Senses for One Death on the polished fronts of squares of volcanic rock. “Throughout the poem, five-counts recur – trees, candles, fingers, nights, mountain peaks – most poignantly in a tender confession: ‘they tell me there are four seasons / but I live in a fifth one / which is your space / and your time’.” To inscribe into stone suggests permanence and stability, while the poem itself acts as a reminder of life’s fluctuations and transience, and ultimately the connectedness of all things — trees, candles, fingers, nights, mountain peaks — and how stone too will eventually erode.

The Weight of Words runs until 26 November 2023