In the current Berlin Biennale, satire becomes a socially palatable language of questioning amidst the city’s tense socio-political climate.

There’s nothing funny about violence. Yet within passing the fugitive on, the 13th edition of the Berlin Biennale, a dark humour lingers amongst some of its 170 artworks. Conceptualised by curator Zasha Colah, satire, irony and parody simmer through artworks that “set their own laws in the face of lawful violence in unjust systems”, existing despite “persecution [and] militarisation”. Colah centres fugitivity – a state of fleeing, evading persecution, defiant and unconstrained by law. In some artworks, wit has become an alternative language of critique in social contexts where realism is deadly. Presented at four venues across Berlin’s centre, this biennale has opened at a time when the German art scene is riven and polarised amidst accusations of censorship and sanctions.

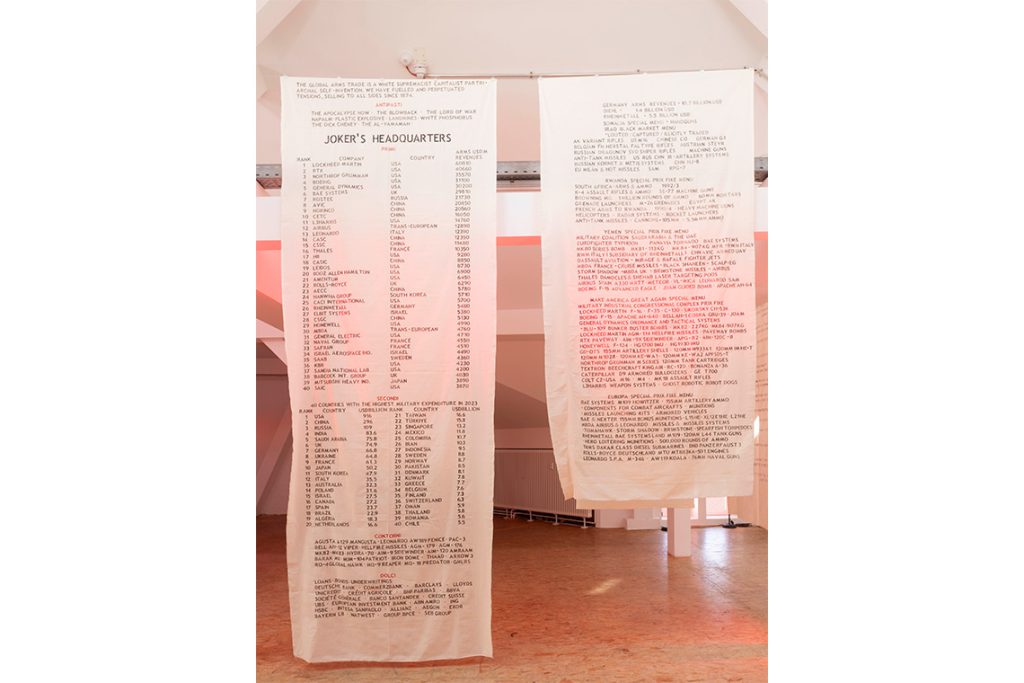

‘Fugitivity’ here is embodied in the Joker, an anarchic outlaw and trickster, manifested through Joker’s Headquarters by Burma-born artist Sawangwongse Yawnghwe, a satirical lair perched in KW Institute for Contemporary Art’s attic. Inside, a bibliography with Franz Fanon and Edward Said on a hanging fabric confronts the visitor. Nearby is an exposé: an enlarged weapons list with manufacturers and origin countries. A tapestry reads “THE GLOBAL ARMS TRADE IS A WHITE SUPREMACIST CAPITALIST PARTRIARCHAL SELF-INVENTION. WE HAVE FUELLED AND PERPETUATED TENSIONS, SELLING TO ALL SIDES SINCE 1874”, while a disguised restaurant menu calls out institutions fuelling genocides. Diagonally across is a two-channel video with the artist (himself in exile) as Joker, mocking global power systems and upholding a collective grievance towards the enmeshment of the cultural industry with capitalism, militarisation and violence. The bibliography is his public plea to reframe thinking beyond Western hegemony. The Joker then becomes an embodiment of public discontent, framing a resonant, collective anger difficult to articulate at present.

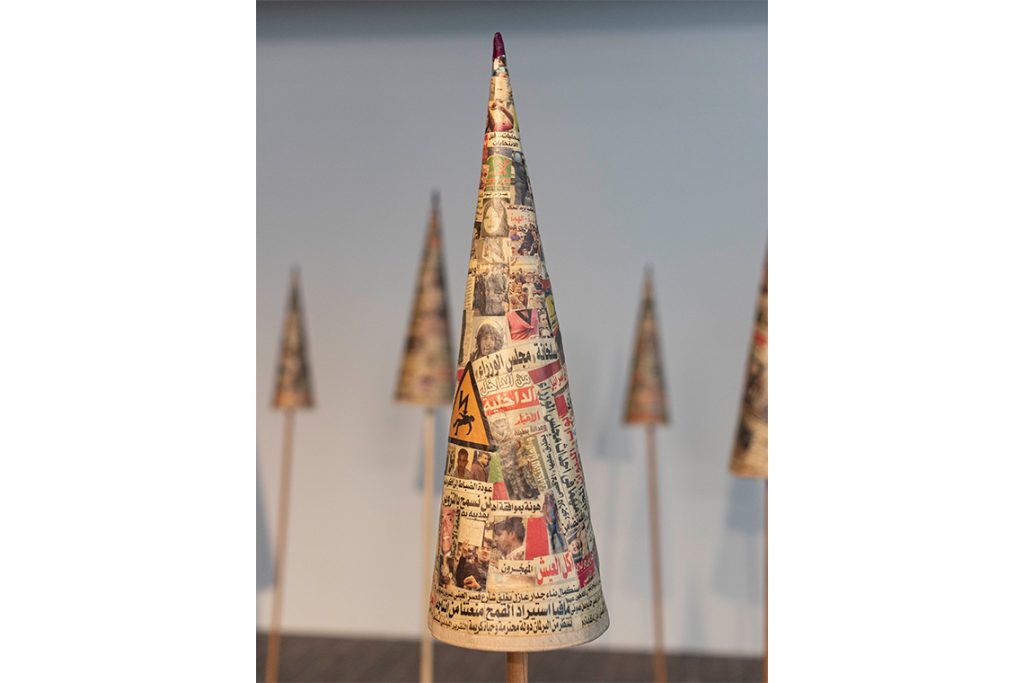

Downstairs, Huda Lutfi’s The Fool’s Journal (2013/14) is on view again following its first presentation in Cairo during the Arab Spring. Conical hats folded from collaged Egyptian newspapers reference dunce caps used to shame the ‘foolish’. A seminal artist and historian, Lutfi puns on the Egyptian media’s control over collective remembering of a revolution, its collaged nature a fragmented piecing together of a mutual memory. Purposely untranslated, the Arabic alienates the non-speaker yet speaks to those who do. Its placement in the biennale is a removal from its context – now a mere foreign object bringing to the fore a language currently ridiculed by racist discourse.

Next door, Sarnath Banerjee’s commentary on the quotidian brings comic relief to what feels like an anachronistic biennale. Interspersed between sketches from his graphic novel Corridor (2004) is Critical Imagination Deficit: easy listening audio snippets of everyday life resonant to diasporic bodies, with colonial residue in the quotidian evident in their witty observations. Presented on structures akin to Indian street newspaper stands, Banerjee reflects his “diagnosis of a fleeting era of intellectual dominance’, what he deems a ‘crisis in Euro-American hegemonic power”.

Photography by Marvin Systermans © Huda Lutfi

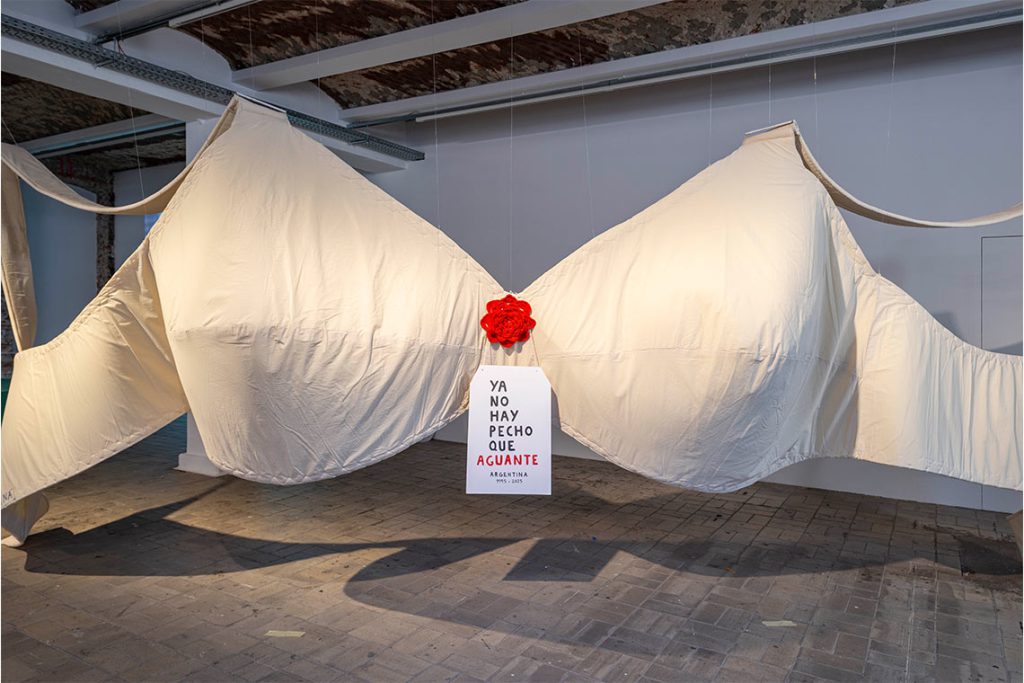

Just below, panties and bras are satirical symbols of revolt against patriarchal power. The walls of KW are pasted with ‘Panty Power’ stickers, a shrine for the 2007–08 Panties for Peace campaign against the abuse of women by the junta in Myanmar. Mobilising women worldwide to mail underwear to Burmese embassies, it is a subversion of the junta leader’s superstitious fear that men’s hpoun (power and honour) destructs if in contact with women’s underwear. Nearby is the giant bra El Corpiño (1995) by Argentinian artist/activist Kikí Roca and her female collective Las Chicas del Chancho. A carnivalesque fabric sculpture recalls disappeared victims of the country’s military dictatorship (1976–83), echoing broader calls for reparative justice by Argentinian mothers and grandmothers.

In Sophiensaele, Major Nom reimagines The Beggars’ Convention (1987), a seminal slapstick play scrutinising the Burmese junta. In its Berlin iteration, Major Nom brings an ensemble that stages a tongue-in-cheek epilogue as a commentary on the strenuous Schengen tourist visa process, a recall of the failure of their ensemble’s own Schengen visa attempts. The mountain of papers and absurd visa officer elicited cackles of agreement from resonating audience members, while some heads awkwardly turned away.

In Moabit’s former courthouse, Franco-Tunisian artist Fredj Moussa portrays a visually poetic yet subtly absurdist critiqueof the word ‘barbarian’. Drawing from fourteenth-century Italian literature set in Tunisia, Land of Barbar (2025) uncovers the xenophobic and colonial roots of the word. The Romans called Tunisia the ‘Barbary Coast’, from which the French word berbère is derived. Moussa’s dreamy, paradise-like frames are embedded with human scarecrows, a tapestry-draped ghost-like figure, an upside-down chicken – ‘uncivilised’ caricatures reflecting the Eurocentric, colonial fantasy of ‘civilising’ the Other.

In another courthouse room is South African artist Helena Uambembe’s How to Make a Mudcake (2021/2025), ink prints on kitchen rags with sarcastic warnings like “May contain traces of whitewash” or “May contain traces of racial killings”. At its centre is a parody cooking tutorial where Uambembe plays an influencer-chef advising how to cope with the lingering trauma of colonialism. With deadpan, wry humour she says: “The more creative you are with your trauma, the better for the art”. Pouring ‘soil’ into her batter, she quips, “it could be messy, but so was colonialism”. Kitschy video transitions underscored by an upbeat jingle create a fitting unsettling gut feeling as she makes her colonialism-laced mudcake.

Satire here becomes a subversive reclamation of agency for those who persistently grapple with residues of injustices committed in the past, a more socially palatable language of questioning. While the issues of historical injustices spotlighted here are no doubt still relevant and enduring in the present, there is an irony in the gaping absence of contemporary injustices being addressed in this biennale: particularly those in the Arab region and even within the city itself. The Berlin Biennale still lives in the past. Perhaps this is the joke, and quite a sombre one, for a periodic exhibition designed to address the current, and with a theme meant to uncover works amidst “lawful violence, unjust systems, persecution and militarisation”.