The colossal exhibition and research project Musafiri: Of Travellers and Guests by Haus der Kulturen der Welt examines migration as one of the oldest constants in human history.

Entering the architectural quirk of the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (HKW) or ‘House of World Cultures’ – also known as “the pregnant oyster” among Berliners – involves reorienting. A foyer is named after Bessie Head, Botswana’s renowned fiction writer; the hall, after Indian sculptor Mrinalini Mukherjee; and the terrace after the Négritude pioneer Paulette Nardal. Each part of the building bears the name of an influential, non-Western woman of colour – sociologists, politicians, psychologists, writers, artists, scholars and musicians. Standing in a Europe mapped and monumented largely after white male European statists, the newness is startling.

HKW’s very design forms the ideal setup for its latest exhibition, which showcases 37 diverse international artists and collectives. Musafiri: Of Travellers and Guests tries to imagine a world more hospitable to movement, without producing irreconcilable differences. It is named after musafir, an Arabic word with iterations in several other languages, including Hindi, Farsi, Swahili, Malay and Uyghur. It mostly denotes a ‘traveller’, but in Romanian and Turkish it leans toward ‘guest’. This fruitful tension between meanings is where the exhibition situates itself.

This is not a mere pro-migration show put on in an increasingly anti-immigrant atmosphere. The scope is far more ambitious and puts its money where its philosophical mouth is. For one, countless undersung regions and communities are showcased, from Mongolia and East Timor to Taiwan’s indigenous peoples, marginalised lovers in Ramallah, Nepali soldiers fighting for Ukraine, and the Japanese diaspora in Brazil. The scale and boldness are salient. A thoroughly impressive catalogue booklet and an additional reader further augment the exhibition’s research enquiries beyond just representation. Both contain an introduction by HKW director Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung and an exhaustive curatorial essay by Cosmin Costinaș, exploring how and why not just different kinds of people but also languages, cultures, objects, ideas, religions and more have always travelled and cross-pollinated throughout history, implying that movement is inherent to our very being. Musafiri does this while decentring European colonial and universalist cartographies and the “hegemonic…inherited programmes of the world”. This allows it to probe the actual capacities for exercising cosmopolitanism in varied societies – especially within underexplored South-South exchanges.

Among the many historical travellers invoked by the show, Lourenço da Silva Mendonça is predominant (a Julien Creuzet commission is about him). From present-day Angola – from where he was serially exiled for his anti-colonial, indigenous activism – Mendonça “filed a case against the Vatican” in 1686 to condemn slavery and won. His arguments were based on “rights [being] shared by all human beings”, regardless of identity or geography, making Mendonça one of history’s first abolitionists.

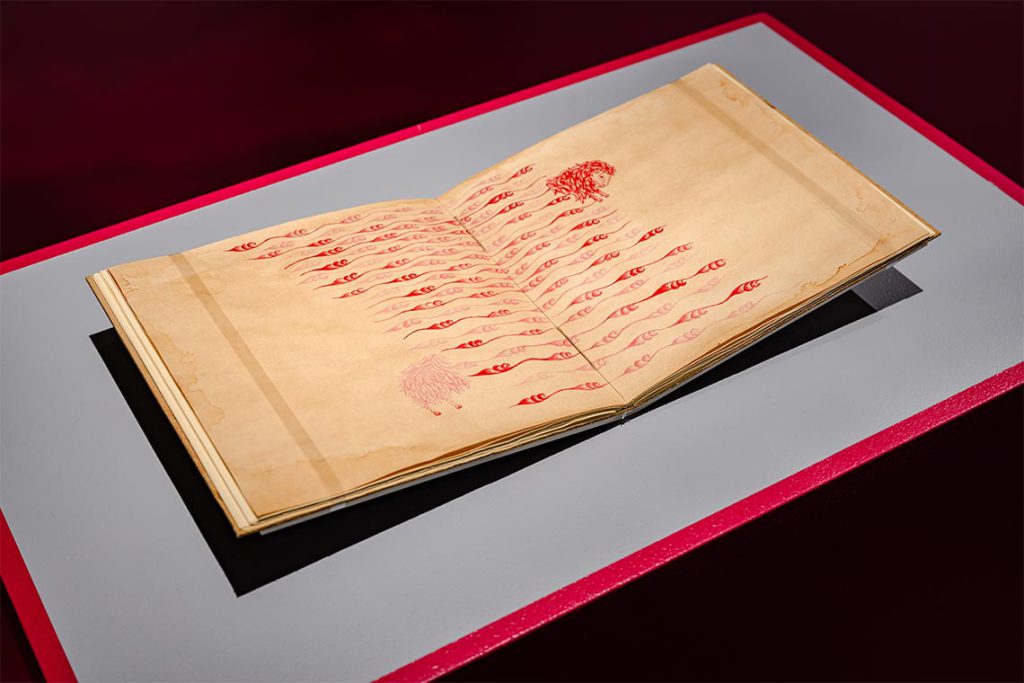

Highlighting such a figure amid Musafiri’s abundant supplementary material entrenches a painstaking political clarity beneath the art. The range is vertiginous, with textiles featuring massively. The opening foyer is draped in enormous localised batiks by Sri Lankan tropical modernist Ena da Silva, while Malian artist Aboubakar Fofana’s Mood Indigo (2011) proffers serene dyed fabrics that are soft on the eye and mind. In Bambara mythology, there are at least twelve shades of blue with different meanings and philosophies. Here, indigo is a dye and also a “healing agent”, spiritual carrier and “sociocultural entity”. Historically indigo was a valuable colonial cash crop, grown with exploited land and labour. There is some curatorial harmony with Aslı Çavuşoğlu’s works featuring cochineal red ink – another early traded Armenian commodity – as well as Monilola Olayemi Ilupeju’s gentle portrait of a poppy field, dust floating above my head like gnats in a daze (2024). The growing and trading of this beautiful flower for narcotics has led to catastrophic conflicts, from British opium dumping in China and the Opium Wars to more recent instabilities in Afghanistan and Myanmar.

One of Musafiri’s primary strengths is its focus on the flows of global capital across time, from ancient trade routes to the setup of techno-capitalist structures like smart cities. Ilupeju’s painting is small, quiet, yet symbolic of Musafiri’s methodology: to subtly incite the viewer in seeing how the logics of imperial expansion and capitalism are inextricably entwined. Another example is Malaysian artist Anne Samat’s stunning totemic installation Wide Awake and Unafraid #3 (2024). Splayed across a whole wall and floor section, it is made of ordinary items like garden utensils, cutlery, knick-knacks, cheap jewellery and more, winking at how much our fickle aesthetic appreciation is influenced by milieu and cost. It also subversively invites the viewer to sit before it in awe, like visiting a temple with a god made of discounted plastic forks. Where is the risk in worshipping and pedestalising what we buy and consume?

Musafiri further delves into the travel of cultural objects and pop culture, especially music. Diane Severin Nguyen’s video IF REVOLUTION IS A SICKNESS (2021) is a standout, centred on a teenage Vietnamese orphan girl in Poland who makes friends through an intense love for K-Pop, a popular phenomenon in the country. Parts of the film are astonishingly haunting, with reflections on alienation, performativity and the aching to understand one’s own body as it is gendered, even commodified. Literally arresting, it also feels more sharply contemporary in the way in which it engages with the newer generation of internet-shaped youth. This connects well with other works interrogating the acceleration of digital technologies – like facial recognition surveillance – and their impacts on how we code our own and others’ bodies.

One of Musafiri’s most memorable installations is Filipino artist Ryan Villamael’s Locus Amoenus (2017–). It springs down from above right as you enter and then later depart: a mass of “airborne foliage”, the catalogue states, slashed and arranged using the traditional Filipino paper-cutting technique of palabat. Villamael’s material is various old colonial maps of the Philippines, which he just slits and slices up – talk about creating alternate cartographies. The artist was inspired by the travels of his father, an OFW (Overseas Filipino Worker), and the larger history of why Filipinos have frequently emigrated, especially via seafaring. Cheekily, Locus Amoenus means ‘pleasant place’ in Latin. Villamael’s intervention is so brilliantly layered – to make something entirely different and more pleasant out of externally imposed borders. To literally deconstruct and dismantle it; to make it look like his land’s leaves instead, or “algal bloom”, or a “mycelial network”; to make it fluid and flimsy and floaty and fantastical; to show how all the reasons why we move or stay are only ephemeral (state)craft. In a brittle political climate, Musafiri makes us feel all the stakes of migration.