The Syrian-born artist’s work reveals a quest for identity and connection, forged through the objects that surround her in her family home.

Canvas: What led you initially to painting?

Yasmine Al Awa: I’ve been painting for as long as I can remember. I always knew that I would go into the art world, so I decided to study art restoration after high school in Florence. I had never considered being an artist until I moved to Lebanon during the pandemic to be with my family. There, my focus shifted to painting restoration, which led me to further develop my practice. I realised too that I felt disconnected from my heritage, even though I was surrounded by my father’s family and my grandfather’s possessions from Syria. That’s when these fragments in my work started to appear, to symbolise how identity is splintered when one moves or is raised abroad.

Could you tell us more about your experience living overseas and your sense of identity?

I was born in Syria, but raised in Dubai. My memories from my Syrian childhood appear fragmented, however, because I have a very strong visual memory. Even my mother is surprised at what I can recall. I never used to feel like I was Syrian because of being raised abroad. Dubai is more of a home to me than there. Whenever I went back to Syria, I felt like a tourist. I think part of me wants to forge a stronger connection with my Syrian roots and heritage through my painting.

Photography by Altamash Urooj. Image courtesy of the artist and Ayyam Gallery

How do you cement this connection in your art?

I’ve always been drawn to Syrian architecture. Syria has a lot of heritage and savoir-faire, and I want to show this underrepresented part of our culture. My grandparents’ home is what I remember most from Syria, so I try to coax out these memories through painting, which is also a way of preserving them.

Your most recent paintings focus more on objects and spaces than human figures. Was there a reason for this shift?

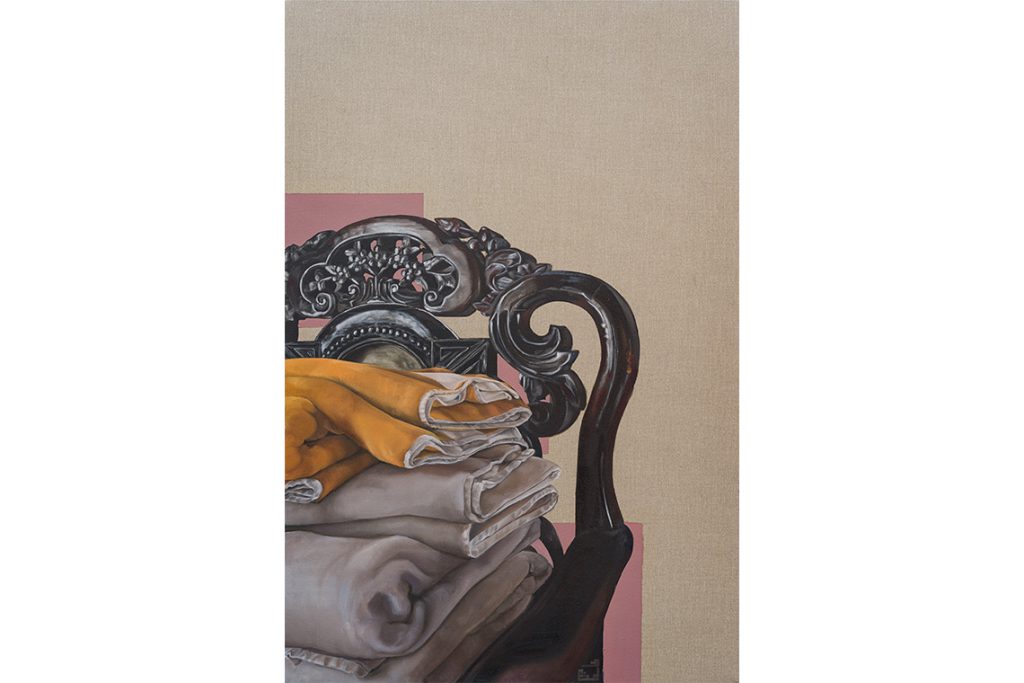

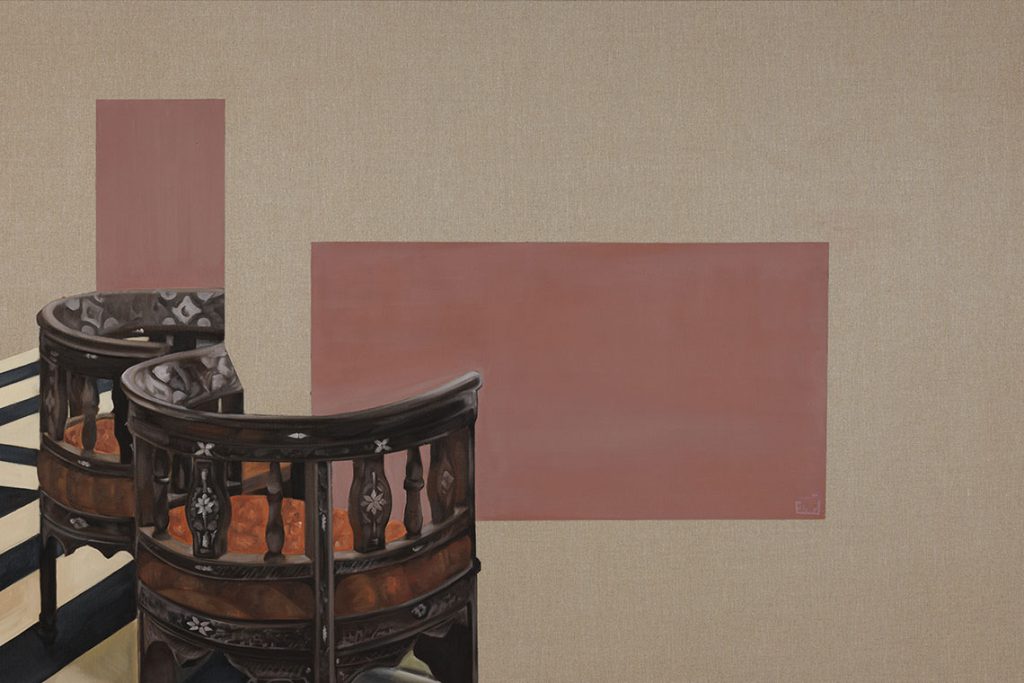

I actually started off painting people during the pandemic, when I had to use my own body since I didn’t have access to a model to represent these figures and fragments. I was also inspired by the pink colour of the walls in my aunt’s house, which I often use in my paintings. Gradually, I was drawn to the complexity of hands and feet, and started to focus more on them. Then I started my fine arts degree, where the emphasis was on still life from pictures of what was around us. I was surrounded by these artefacts, chairs and tables, which were once my grandfather’s, and would incorporate their details into my work. I eventually realised that identity also comes through objects.

During the fall of the Assad regime in 2024 the president’s home was looted. Even though it was full of expensive things, people were taking more personal items, like books. Objects and elements are a representation of a person, so when they were looting these books, they felt like they were destroying the idea of him as well.

What do objects such as the pomegranate in Contained Fertility I and II (2025) signify to you?

In this case, the pomegranate, which is a symbol of fertility across the Middle East, is being used to represent the region itself. It’s a symbol of how I feel that I am from all the places where I’ve lived, which have all been in the region. The addition in this case of the hands reaching out depicts the idea that we’re continuously rebuilding ourselves.

How did the recurring motif of the chair begin, such as in Linear Trace (2025)?

The chair is a symbol of family gathering. The particular one I paint, which was featured last year in the Ayyam Gallery summer show, is a Ming Dynasty chair. My grandfather used to import artefacts from China and Japan to Syria, so we have a lot of these objects at home. He passed away when I was young, so I think painting these pieces of furniture is a way to create a bond between him and me.

What do you hope someone viewing your work takes away from it?

I hope for people to see that Syria is not just about war. We have one of the oldest cities in the world, there are educated people in Syria, and even though we were closed off for a long time, there are people there who are resilient and committed to their work. Historically we have forged a certain aesthetic, one that has borrowed aspects of many different cultures and which represents who we are as people.

How do you see your practice evolving in the future?

I always need long stretches of time to paint, which is not always easy with other demands like university and working in a gallery. But once you have momentum, you don’t want to stop. I’ve always been very stuck in these academic rules of proper technique. There is an abstract artist who paints in Ayyam Gallery. No rules, all brushstrokes. Seeing his technique has made me want to explore incorporating my sketching into my painting. I feel like I need to free up my brushstrokes right now.

This interview first appeared in Canvas 121: If Walls Could Talk