The artist thrives on states of change and evolution as she builds up, and breaks down, aspects of the world around her.

“I am a hybrid,” says Zeinab Alhashemi, the Emirati conceptual artist whose works – monumental site-specific installations of building materials and camel hides – are also curious amalgamations. She extends the analogy to herself because of a catastrophic car accident in 2009 which left her badly injured. “Everything changed. I ended up in hospital with 13 fractures and had 11 surgeries, including a hip replacement,” she explains. “I am part of that human interference. I am half natural, half artificial.”

That awful incident was the unlikely catalyst for her career. “Through my recovery, between 2009 and 2014, I think I was just numbing my trauma by making stuff. I was very experimental,” she says, recalling how she embraced a thriving ecosystem of artistic residencies, cultural hubs and travel subsidies. “I was just escaping my reality of recovery.” Alhashemi began by creating Pop artworks and collages, but over the past decade she has focused on public installations. Geometry and urbanism – her sculptures often utilise materials such as steel and concrete – are recurring themes, as well as the resilience and organic order found in nature. In addition to her site-specific projects, she has worked on wall-hanging neon scripts and pieces of digital scenography that explore topographical aspects of the UAE.

Alhashemi describes her work as a “glimpse” of what is happening around her in the region, a place of profound – and ongoing – change. “I reconstruct something I see and deconstruct it in my own vision,” she explains. She is interested in the state of flux, the sense of becoming, of things being unfinished, and her work brings that philosophical consideration to the context of the modern history of a country altered by the discovery of oil and subsequent development projects.

Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection is another influence. “The idea that all intelligent species select what works for their environment in their favour is intriguing to me,” she says. “I believe that the concept of natural selection can be applied to many different areas of human life, from business to culture and society.” But her work offers neither nostalgia nor industrial futurism. “I try to live in the duality. I don’t try to judge it.” And so, in her work, we find remnants of the ancient culture of camel breeding as well as evidence of contemporary construction and the extraction and consumption of natural resources.

Alhashemi was born in Dubai in 1986. “As a child I was always into scribbling, doodling, painting,” she remembers. Creativity ran in the family. Her father won a scholarship to study film in London, after which he returned to the UAE to pursue a career in television and media. As a teenager, she was intrigued by the large abstract canvases of the celebrated UAE painter Dr Najat Makki (see page 166), a relation on her mother’s side of the family. “She was one of the very first women to study art in Egypt and came back to be an artist,” Alhashemi explains. “There was a moment when my mum shared with her some of my drawings and I was very embarrassed. I remember, she looked at them and said: ‘I would love you to just think about not copying what you see but what is it you want to tell? What are the colours that you want to work with?’ Those words were quite interesting to me. I think she was trying to tell me to do what I want, not what I think is right.”

Alhashemi earned a BA in Arts and Science from Zayed University, having studied visual art with a major in multimedia design. Initially, she considered a future as a product designer. “There was this idea of making things,” she recalls. “I wasn’t one of those confident people who said, ‘I’m going to become an artist’. I was still vulnerable and quite shy about what I wanted to create.” Following the car crash, she developed an artistic practice that included design-led pieces and large-scale installations. She contributed to Dubai Design Week and collaborated with brands, whilst being sensitive to critical distinctions between commercial work and artistic expressions. “I was trying to understand the DNA of my work,” she recalls, adding that it was all part of a “journey to healing”. Her working process today involves collaborations with a variety of workshops that help her fabricate structures, as well as with the slaughter houses that provide the camel hides. It’s a challenging process, she notes, as there are few establishments used to working with artists. “You need to build relationships. You need to build trust.”

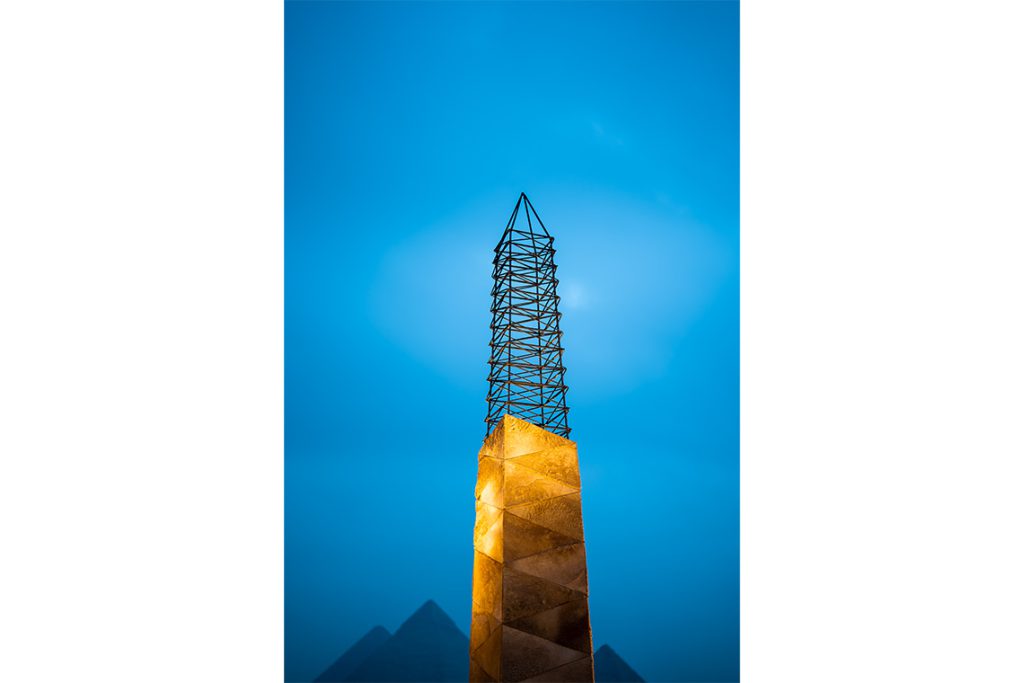

Alhashemi has steadily fostered a following in the flourishing UAE art scene. She participated in the Sharjah Biennial 11 (2013) and CoLab: Contemporary Art & Savoir Faire at Louvre Abu Dhabi in 2018, at which she presented Metamorphic (2018), a piece that fused panels of stained glass into a grid of metal mesh. “In the past three or four years there has been a demand for and interest in public art,” she says. Following the Covid-19 pandemic, Alhashemi had a flurry of major projects. In 2022 she presented Camouflage 2.0 – a portmanteau installation of rock-shaped structures faceted like gems and covered in camel leather – at Desert X AIUla and a related obelisk-style form for the second edition of Art D’Égypte at the Pyramids of Giza. The same year she was shortlisted for the Richard Mille Art Prize at Louvre Abu Dhabi.

Image courtesy of the artist

Alhashemi’s most recent commission, exhibited at the Theseus Temple in Vienna (ended 13 October), is There May Exist, a large pyramid of oil barrels covered in camel fur and hide, materials dyed in the oasis city of Al Ain, near the UAE border with Oman. The work, she explains, addresses how humans and animals adapt together to their environment, as well as speaking to issues around sustainability. Her works have been exhibited on sand dunes and town squares and in galleries, but the subject matter gathers them all together. “It’s like looking at a camel caravan,” she observes. “That caravan is going from a desert to a city to a building to an outdoor area. Once they rest, they transform into something.”

Following the Vienna exhibition, she has a new solo show this autumn at Leila Heller Gallery in Dubai. She is also contributing to the Public Art Abu Dhabi biennale in November and is opening a new studio in a large warehouse in Abu Dhabi. “There are a lot of more complicated things I want to create,” she says. The precarious equilibrium between progress and decline – as history spins ever forward – continues to reverberate through much of Alhashemi’s work. She likes to quote HH Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, the founder of the Emirate of Dubai, who once observed: “My grandfather rode a camel, my father rode a camel, I drive a Mercedes, my son drives a Land Rover, his son will drive a Land Rover, but his son will ride a camel.” Does this suggest that we all return to our origins? Alhashemi laughs. Conclusions are beside the point, she maintains. “I will leave that question unanswered.”