The exhibition Zifzafa at Barakat Contemporary, the first solo show in South Korea by Lawrence Abu Hamdan, complicates the positive image of wind farms as a green energy source. By revealing how their by-product – noise – is mobilised to subjugate and expel the Jawlani Syrians from their land in the Golan heights, it highlights the community’s resistance to Israel’s wind turbine project.

Tickling my ears as I step into Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s exhibition Zifzafa, at Seoul’s Barakat Contemporary, is a cascade of frenetic saxophone notes emitted by a large, vertical bass amplifier facing the entrance. Projected on its meshed surface is a man – saxophonist Amr Mdah – passionately playing the saxophone on the balcony of a farmhouse. His fingers glide across the instrument, improvising notes, and his body sways rhythmically in a way that happens only in the midst of complete absorption. Clips of a tree, branches, reeds and clouds cut in every two or three seconds, mirroring the breathy fluidity of Mdah’s music.

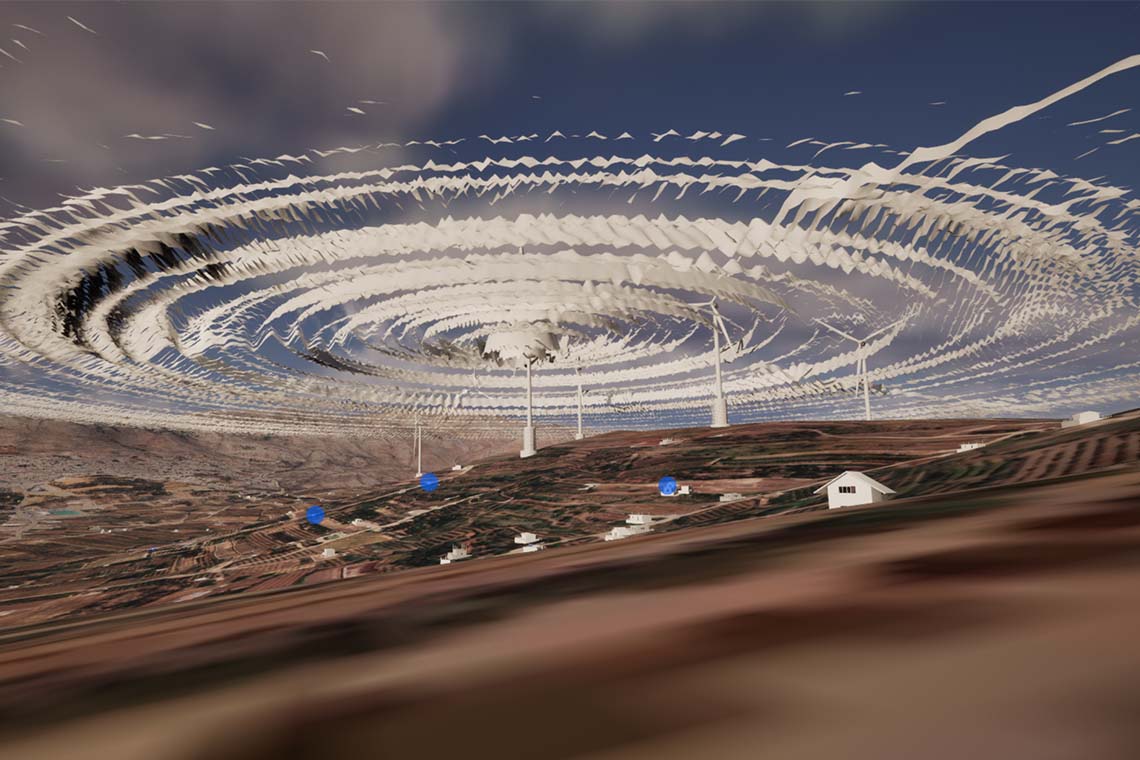

On either side of the captivating audiovisual installation, Wind Ensemble (2024), are works that extend the saxophone tune’s agitated energy. Haze (2024), with black speckles that coalesce into forms resembling stage drapery, takes up an entire wall in the gallery, introducing subtle tension into the otherwise pristine white cube space. Across the room, in Tilting at Windmills (2024), billows of blue-and-black digital clouds swirl ominously, enshrouding what appear to be scenic landscapes. A wind turbine peaks from behind the plume on one of the screens, hinting at the sociopolitical context underlying the work.

Image courtesy of the artist and Barakat Contemporary

As a researcher, filmmaker, artist and activist who investigates sound to expose the violence embedded in hegemonic systems of the world, Abu Hamdan amplifies the voices of marginalised communities. In Zifzafa, he once again foregrounds such a group: the Jawlani Syrians, who have lived under Israeli military occupation since 1967. Today they face a renewed threat from the Israeli government’s plan to construct 31 of the largest land-based wind turbines on their last remaining open space in the Golan Heights, close to their homes. The deafening noise of the turbines will engulf everyday sounds born from the Jawlani’s communion amongst themselves and with their land, disrupting both their personal and collective lives. Eventually, the unbearable noise will force the Jawlanis off their lands.

Meaning “a wind that rattles and shakes all in its path” in Arabic, zifzafa serves as “a conceptual tool to map a network of social relations transformed through and by wind” in the exhibition, as the show’s foreword explains. The speckles of Haze are a spectrograph of the sound generated by a 250-metre-tall wind turbine, while the gyrating dark masses of Tilting at Windmills visualise the perimeters of the sonic turbulence created by the turbines. The full context is revealed in Zifzafa: a video-game essay (2024), installed in the gallery’s basement.

Image courtesy of the artist and Barakat Contemporary

Although referred to as a video game, the work is more of an interactive virtual map in which visitors, using a joystick, may walk around the planned wind turbine sites across the Golan Heights. Throughout the 45-minute runtime, I listen to accompanying soundbites recorded by the Jawlani musician Busher Kanj Saleh, ranging from the crackles of the land as a man’s shovel ploughs the soil to the deep calls of cows spilling out from a cowshed and a male voice booming from a speaker on the wall of a house, joyfully inviting neighbours to a Friday afternoon wedding ceremony at Bride’s Hall. Interspersed are eight narratives that collectively frame the wind turbine project as yet another oppressive practice deployed by Israel since 1967 to erase and subsume the Jawlanis. As I listen in, the wind turbines – so idyllic and peaceful on the screen – transform into monstrous forces that imperil Jawlani social life and memory.

Indeed, with a simple click of a button on the game controller, the room is flooded with the thundering roar of wind turbines. As the relentless whir pounds against my eardrums, the disorientation and stifling isolation that will be felt by the Jawlanis in their homeland become palpable.

The most powerful moments in Zifzafa: a video-game essay arise in narratives that expand the conflicting perspectives on the wind turbines to question Israeli – and Western, by extension – ideologies and systems, while repositioning the Jawlanis as social agents who shape their beliefs based on their lived experience. For example, Israeli advocacy for wind turbines as a good, green energy source is presented as “seeking to sign international accords, extract the wind, pump decibels of noise into the atmosphere, deliver vacant reports, cull hundreds of cranes, eagles and bats per year, ethnically cleanse a land of its inhabitants and, while doing all that, squeezing a profit from occupied lands made barren by militarism.” In contrast, the Jawlanis’ rejection of the turbines is reconsidered as a “refus[al] to see the world as it is sold to them,” instead relying on their lived experience to decide what is right for their land – a crucial stance in the struggle for self-determination.

Abu Hamdan’s skill in weaving compelling narratives through rigorous research and collaboration with local communities shines throughout the work. For it to fully resonate with the users, it could perhaps benefit from a reconsideration of the current title. While “video-game essay” suggests interactive tasks or challenges commonly associated with video games, Zifzafa: a video-game essay instead unfolds as a nuanced immersive journey, which may initially disorient users and lead to their early disengagement from the work.

Since 2019 the Jawlanis have resisted the construction of wind turbines by erecting more ‘kookhs’ on their land. These traditional small shelters or farm-buildings are an important physical presence and serve multifarious purposes, described in Zifzafa: a video-game essay as including the housing of “drums, rakes, bees, guests, books, inflatable pools that no longer inflate, tyre chains, spiders, snakes, beds, memories, dinner, whisky, gossip, pleading and laughter in all kinds of languages”. In Wind Ensemble (2024), the Jawlani saxophonist Amr Mdah plays from the balcony of a kookh, and his playing is less a performance for an audience than a proclamation of existence, resistance and self-determination. Clips of a tree, branches, reeds and clouds intercut every two or three seconds, shielding his body from the viewers’ objectifying gaze. Mdah’s notes – frenzied at times and pensive at others – stand for the chaotic vivacity and melancholy of life. As the branches, flowers and reeds tremble and clouds drift with zifzafa, the land and sky of the Golan Heights become one with the Jawlani saxophonist, evoking the deep connection and shared memories that bind them into an inseparable union.