The artist reveals how his layered use of colour represents narratives of destruction in his latest body of large-scale collage works.

Canvas: How have you developed your recent work in collage?

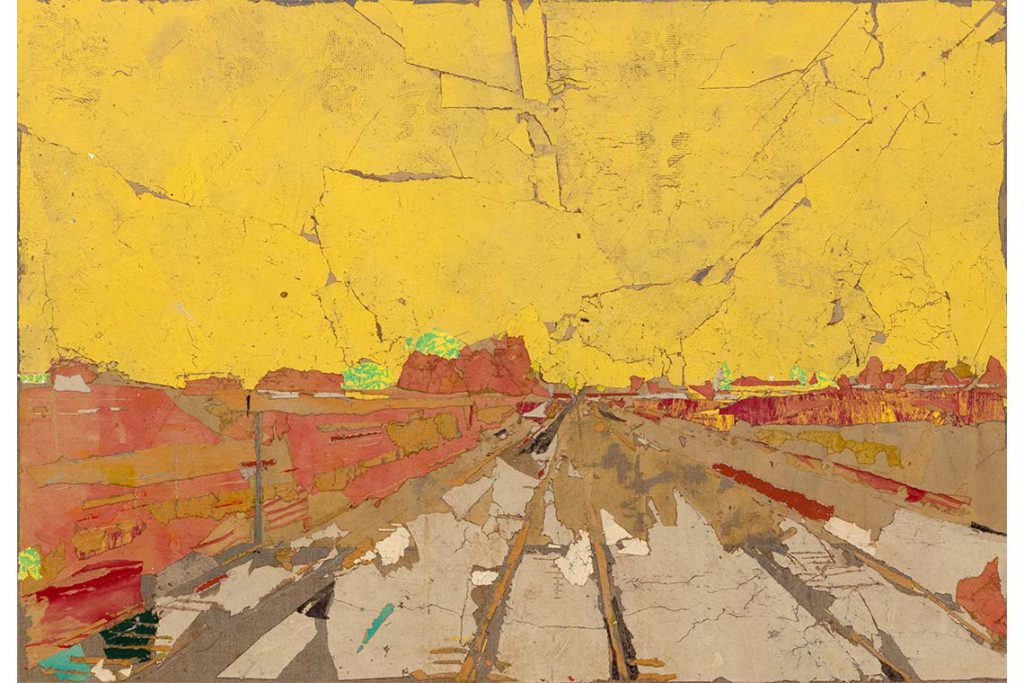

Tammam Azzam: I started collage six years ago, as a new medium for me to understand the deep feelings I have concerning broken things and their fragments. I think the idea actually first came many years ago, wrapped up in other works I made in Syria like my Laundry series (2008), in which I experimented with collaged and ripped clothes. When I moved from Dubai to Delmenhorst, which is in the German countryside, the physical reconnection with nature made me vividly remember the village in Syria where I first came from, purely through the clearness and variety of colours. For about 12 years previously I had only used black and white in my practice, but this was no longer able to fully describe the emotions that the new environment had awoken in me. Expressing this effect in words is very difficult, but it explains why I’m exploring this technique of layering colours over each other.

How do you build the imagery of each artwork?

I’ll have a destination in mind that I work towards, but I never know which details the journey of each artwork will reveal. The geographic places that I build either don’t exist any longer, or never did in the first place. I have to reconstruct them from fragments of memory, light and colour, using abstract details to create somewhere that only exists in this window. Sometimes one photo could be the reference for a whole piece, but often it’s a much broader mix of personal recollections. Just copying from a photo doesn’t create a unique voice, so I hold multiple stories in my mind together simultaneously. Sometimes these are very clear, as if right in front of my eyes, sometimes I have to recall them from years ago in childhood. I might not know exactly how it comes, but I’ll know this part is from Syria, this colour is from Germany, these lines are from Dubai.

I also feel that current events reference previous lives. For me, a reference to a destroyed building might have originated in Syria, but it’s not specifically about Syria. The theme is about the destruction of buildings on top of their inhabitants, which can sadly be seen everywhere.

The materiality of collage, which involves ripping and tearing paper, has a specific relevance to themes of destruction. How do you use this technique to plant narratives beneath the artwork’s surface?

This is the daily conversation that I have with each artwork. Each layer is a part of the work, even if the audience cannot see it. To build something from scratch, you need to really build it up from its foundations, even if they will end up hidden. These layers also create the relationships between surface and sub-surface colours. However, the way people connect with my work is always different to how I expect. The only judgement I can trust is my own, and I don’t let a work go from my studio until I know it’s become something that I would like to see myself. It’s my personal language, and the only way to express it is via this method and waiting.

Do you approach the architectural structures in your artworks any differently to the landscapes?

After 20 years I have realised that I’m always fond of the emptiness of places, and also of the horizon itself. Both of these things together make up the main structures of the work, and I’m always looking at what’s going on in these empty places. It’s up to me to reconstruct a sense of emptiness. Sometimes it comes from the long line of the horizon, sometimes from aspects of an abandoned village, sometimes from a city like Berlin. The city is a big theme for me. Living in it, witnessing the movement, you think about the life and story behind each building.

Yet I always imagine myself standing within the landscape that I’m building, both witnessing and controlling the scene. That’s why I rarely include any human figures, because that would feel like I’m replacing my story with someone else’s, somebody whom I don’t know. In the end it doesn’t matter about the specificities of the geographic place, only the idea of absence.

How much of the thematic emptiness, destruction and fragmentation in your work was born from witnessing the devastation in Syria?

I left Syria in 2011 after the revolution, and moved to Dubai with Ayyam Gallery, because I had actually worked with them since 2007 as a graphic designer. When they moved to Dubai from Damascus I moved with them. After the first two or three years I got used to the craziness, and focused more on building unique artworks. In some ways, it’s more intense to be isolated in your studio, rather than hearing news from Syria and the Middle East 24/7. When I am in the studio I’m connected in other ways.

My series Freedom Graffiti (2013) [which digitally layered Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss (1908) over the facades of war-torn buildings in Syria] was a more direct response to the incongruity of war and certainly contained themes of hope in the aftermath of destruction. But for me it’s all about layering ideas and images together. After I moved to Dubai I began to work with photomontages, which also formed the conceptual core of my Syrian Museum series (2013).

How does your show Diary at Ayyam Gallery develop these themes?

This is my first show in Dubai since 2019, and represents the culmination of five years of work. Coming back to Dubai felt very special as it’s where I came from. Not as in my homeland, but professionally it’s where my career began. That’s how the title ‘Diary’ originated, as it has the sense of a retrospective documenting the way in which I’ve developed my materials over the past five years. Presenting works on such a large scale is also important for me, so that they fill your peripheral vision and position you within the landscape.

Why are you drawn to colour as a means of expressing complex references?

I was first a painter, and am always trying to uphold the fundamentals of painting, which to me means finding or making new colours. However, in paint colours can be blended together, whereas with collage they remain distinct, and I can only create new relationships between them by overlapping and juxtaposing them. It gives me a way of presenting fractured images that abstractly reference objects. My idea is that even in the aftermath of destruction, you can identify all the small parts of clothes, or fragments of toys, by their very clear colour. Each block of colour could refer to any number of objects or places from my memory. I follow a tone for each work. It’s not musical but visual, and leads me from colour to colour.

When I look at the sky, especially in the evening, there is a range of different shades of oranges, pinks, blues or reds. In my art I am able to take even the smallest fragment of colour and expand it to cover the full sky, which creates a sense of astonishment. I can take it from anywhere, and expand my own discovery of colours through this magnification process. Sometimes, however, even though my choices are taken from real life, the colour doesn’t work in this position, and I find that these fragments of truth are actually unable to reflect the reality they’re portraying.