Palestinian artist Majd Abdel Hamid’s first solo show in London at Cell Project Space showcases the contemplative resistance of his textiles.

Cell Project Space, tucked off the main road in Cambridge Heath, east London, unfurls at the end of an outdoor pathway canopied with plants. It’s a small, contained, airy white space and rather cell-like, in keeping with its name. Even before entering, you feel like you’ve journeyed into an alternate world, indeed a sanctuary or hidden enclave, where time is slower, more leisurely, like the swaying leaves above your head. The door opens to Daydreamers, the first solo exhibition in London by Palestinian artist Majd Abdel Hamid, a multimedia artist who primarily works with embroidery. To him, it’s a “technique of recording, reflection and refusal”, reads the little paper catalogue, penned by curator Adomas Narkevičius.

Daydreamers presents work spanning several years of Hamid’s career, going back to 2012. Some of the series on display are complete, while others are still in progress. Like many SWANA and postcolonial contemporary artists, Hamid aims to interfere with constructions of time: attention spans, work hours, time spent vs time wasted, the frenzy of algorithms and the “accelerationist logic” of both media and urban centres. This particularly includes London as a gargantuan, fast-paced city, “where time is hyper-optimised and monetised”. No wonder, then, that the show invokes daydreaming, an imaginative act unbound by the strictures of schedules and resistant to external demands for labour and attention.

Image courtesy of the artist and Cell Project Space

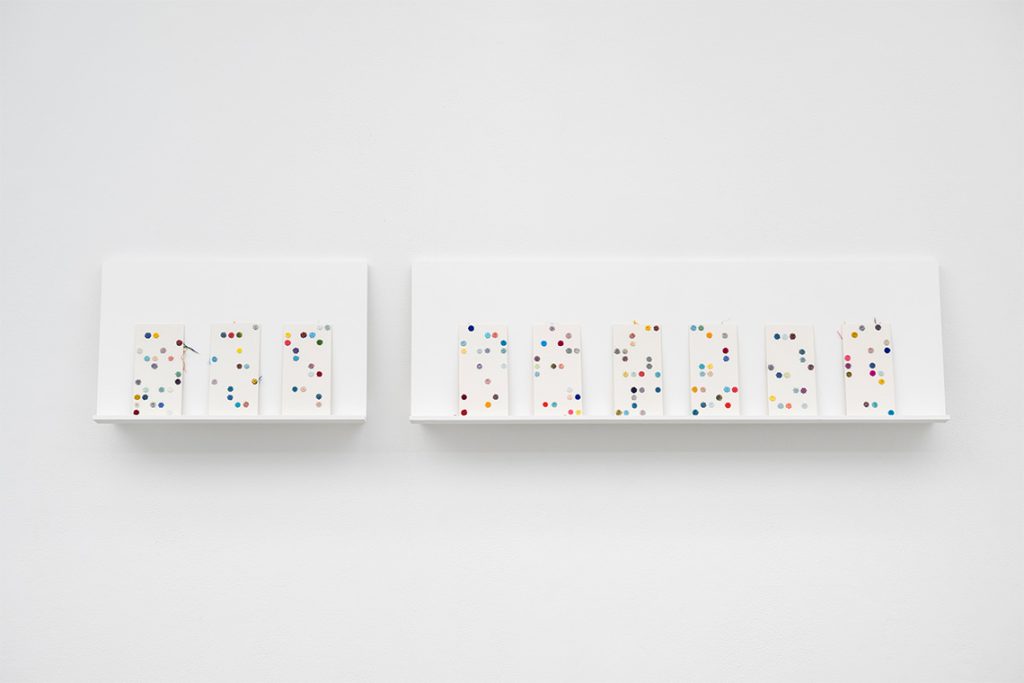

Hamid’s textile pieces are small and considered, and you can see the slow, repetitive stitching formally defying time’s usual diktats. His series Daydreamers (Code) (2024–) includes pieces of unused fabric that Hamid has collected in his base, Beirut. Once they have started to fray, he unravels and picks at them, before weaving them “into small circles”, each circle corresponding to a different fabric. The final stitched patterns are meant to comment on the binary system of 1s and 0s that forms the basis of computer code and specifically the Jacquard loom punch card, a piece of nineteenth-century European machinery foundational to the development of automation.

The leftover fabric from this patient and intentionally laborious process – finding, picking, fraying, weaving, reconfiguring – is then used to make textile fortune-tellers, like the folded origami used in children’s games, where various options reveal different future outcomes for the player. Daydreamers (Fortune Tellers) (2025–) is a “carpet” of over 600 fabric fortune-tellers in a variety of colours, but there are no inscribed options here. In societies where most of us are directed towards prescribed futures – depending on our positionalities, bodies, and purported abilities – Hamid leaves things blank and open, ready for us to imagine and decide for ourselves. In the final two weeks of the exhibition, these fortune-tellers will be gifted freely to visitors, deliberately countering the big city culture where things are rarely provided with no strings attached.

Image courtesy of the artist and Cell Project Space

In the small downstairs room of the gallery, there is also a work from Hamid’s long-running series 12-23 (End of Chapter) (2012–23). This series comprises portraits of Mohamed Bouazizi, the 26-year-old Tunisian fruit vendor who self-immolated on 17 December 2010, triggering both the Tunisian Revolution and the wider Arab Spring. Hamid had initially invited a woman from Farkha village in the northern West Bank of Palestine to embroider one portrait, and she extended the invitation to seven more, with Hamid embroidering the ninth and final portrait. This process extended over a decade, with each portrait changing in form and chipping away at figuration itself, like a long game of Chinese Whispers. Hamid’s final portrait is merely Bouazizi’s name stitched onto a white pillowcase with the thread that was left over from the earlier portrait commissions. The work is presented inside one of the drawers of a dark wooden chest, where the remaining drawers contain other textile and multimedia works by the artist that interrogate cycles of time and repetition.

The politics are quiet yet pointed. Through a series like 12-23 (End of Chapter), you can see how historical acts and iconographies of revolution – itself a proposed futurity, enacted – are passed down and dispersed across the SWANA region and beyond over many years, keeping the flame of an ideology both alive and evolving. Daydreamers (Code) (2024–) threads together subtle anti-capitalist rhetoric. Dotting the exhibition further are works like the delicate Ode to the Sea (Soap) (2024), made of Aleppo soap with a spiralling mound of silk embedded at its centre –– a tribute to the quotidian objects that Hamid often uses and incorporates in his work. These are everyday items infrequently regarded with tenderness or meaning amid the daily grind.

In the absence of wall text and labels, the paper catalogue does the heavy lifting. It’s highly valuable and enriching; when text complements the object, it is precisely Hamid’s careful conceptualising that calmly reveals itself, like film developing in a darkroom. The sparing curation and small size of the works also demand patience and closer contemplation, forcing viewers to slow down and pause. It’s barely an ask, in the face of perceptive art that has taken literally thousands and thousands of hours to create.