Celebrating how heritage can still be a part of contemporary life, Fragments of Folklore in Riyadh’s Jax District seeks to offer a fresh perspective.

Exploring how heritage can repositioned as a living, evolving narrative rather than simply a relic of the past, the exhibition Fragments of Folklore spotlights how artists reinterpret cultural heritage through modern media including geometry, calligraphy and abstraction. The show presents four artists – Lulwah Al Homoud, Rashid Al Khalifa, Raeda Ashour and Hamra Abbas – who each explore a different interpretation of how heritage can be reinvented and shaped by contemporary life, drawing on personal experiences and collective narratives that keep traditional cultures alive.

The show is conceived and curated by three cultural platforms dedicated to furthering discourse around Middle Eastern art: Saudi Arabia’s Thaa, Mir’a Art, based between Paris and the Middle East; and Triyad from Belgium. The three initiatives worked together to present a varied and nuanced approach to contemporary arts inspired by traditional craft, architecture culture or stories.

“It’s an exhibition that not only questions but also revisits the idea of folklore itself. How it should be perceived, whether it’s a living thing within us or a tradition that was created hundreds of years ago and is no longer changeable,” co-curator and Mir’a Art founder Nadine El Guiddawy tells Canvas. “The artists are each part of a larger whole, constituting a specific fragment within this overarching image, with their own technique or style, inspired by the region in which we live. They are all reinterpreting heritage and culture in a new contemporary way.”

The exhibition space is intimate and immersive, its maze-like scenography by Mohamed El Sharkawy inspired by a traditional Najdi village with houses made of natural materials, such as mud brick and acacia wood. The show opens with a fragment of the first-ever painting by Al Khalifa, which he made on the wall of his family residence with left-over enamel paints from a school project when he was 14 years old in 1966. This childhood home went on to become RAK Art Foundation, a platform founded by Al Khalifa in 2020 and dedicated to supporting artists in Bahrain and beyond.

The artwork, preserved at the site, marks the genesis of a folktale, becoming entwined with the fabric of local culture in real time and symbolising heritage in the making. “I think it’s a gesture, that first beginning of a story, an instinct that now becomes folklore. It’s not always words or myths, but the gesture itself,” Triyad founder and co-curator Lisa de Boeck says. “Sometimes it begins as a response to emptiness, a private compulsion to transform the ordinary into something that pulses with meaning. It invites us to ask not what a culture is, but how it is carried, whether across bodies, time, surfaces and silences.”

Other works by Al Khalifa dot the space, including examples of his more abstract 3D pieces, inspired by the minimalist modernist architecture that swept through Bahrain during the 1960s and 70s. Some of these combine enamel-painted aluminium with the essence of a mashrabbiyah window shade, with simple structural designs forming the usually decorative lattice.

Al Homoud, known for her contemporary approach to traditional Arabic calligraphy, Sufi poetry and religious stories, presents a number of works from across her career. Some distort traditional calligraphy aesthetics into something more modern – often drawing on geometry, colours or lines that are very different to the rigid rules used in historical scripts.

The show includes a few of works from her The Language of Existence series, in which she created her own language, corresponding to the letters of the Arabic alphabet, to inscribe the 99 names of God in Islam. “Since childhood, I have been drawn to the art of writing,” says Al Homoud. “During my MA at Central Saint Martins, I sought a deeper understanding of the Arabic script, particularly its evolution across time and space. This exploration inspired me to create a new alphabet, where geometric patterns become the words themselves, based on a mathematical module. I believe that mathematics is the language of creation, and through this approach I reinterpret Islamic artistic traditions to develop modern, timeless and futuristic patterns.”

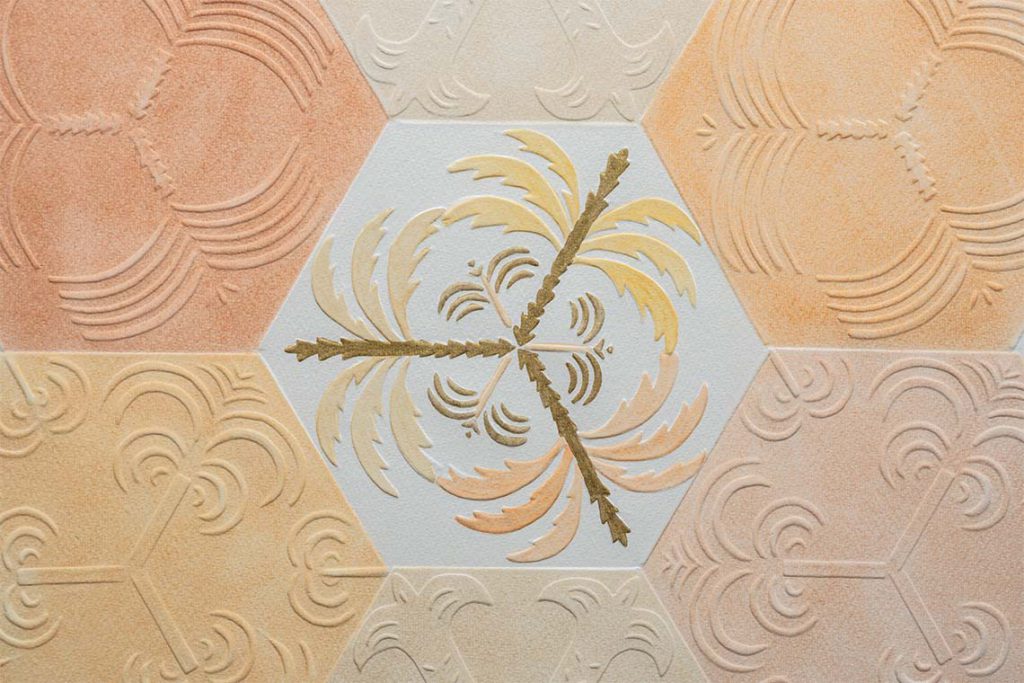

Ashour brings craft and ancient architectural heritage into her artworks, creating geometric pastel-coloured compositions that draw the eye. Through the unique skill of paper embossing, she preserves patterns and symbols from around the Kingdom, stamping motifs based on the millennia- old petroglyphs that adorn the rocks of Al Ula to more recent decorative symbols found in traditional village homes.

“I approach the theme of folklore by introducing and visualising as many traditional architectural elements, folk art symbols, motifs and engraved designs as possible in my artwork, to showcase their richness and beauty,” she explains. “I have developed a unique signature hand-embossing technique on paper, which grants me the precision and freedom to celebrate the grandeur of Arab and Islamic artistic legacies. I utilise gold leaf, pastels, watercolours and photo prints to create my pieces.”

To round off the quartet, the visually striking stone murals by Abbas bracket the sides of the exhibition hall. Aerial Studies – here comprising three pieces from an 11-part series – is made entirely from perfectly assembled marble inlays in an array of monochromatic hues, based on aerial views of the Karakoram mountain range in Gilgit-Baltistan, a part of the world that is especially vulnerable to climate change.

At the opposite end of the hall, Garden 4 is a more colourful affair, a fresh take on Mughal gardens depicting a natural paradise and made from lapis lazuli, serpentine, calcite, jasper and granite. “These works are based on an old technique of stone inlay that originated in Italy and has been practiced in South Asia since the seventeenth century,” Abbas says. “I have reimagined this technique to create a new visual language that blurs the boundary between painting and sculpture.”

While the mediums and techniques of each artist are diverse, they are united in demonstrating that folklore is anything but static, acting as a dynamic source of inspiration that is constantly being reshaped and revitalised by the present; able to resonate with future generations, who will in turn create their own folklore.