The Tunis-based artist reveals the influences behind her drawing practice while shedding light on the Tunisian and wider Maghrebi art scene.

Canvas: How does being a self-taught artist affect the aesthetics of your work?

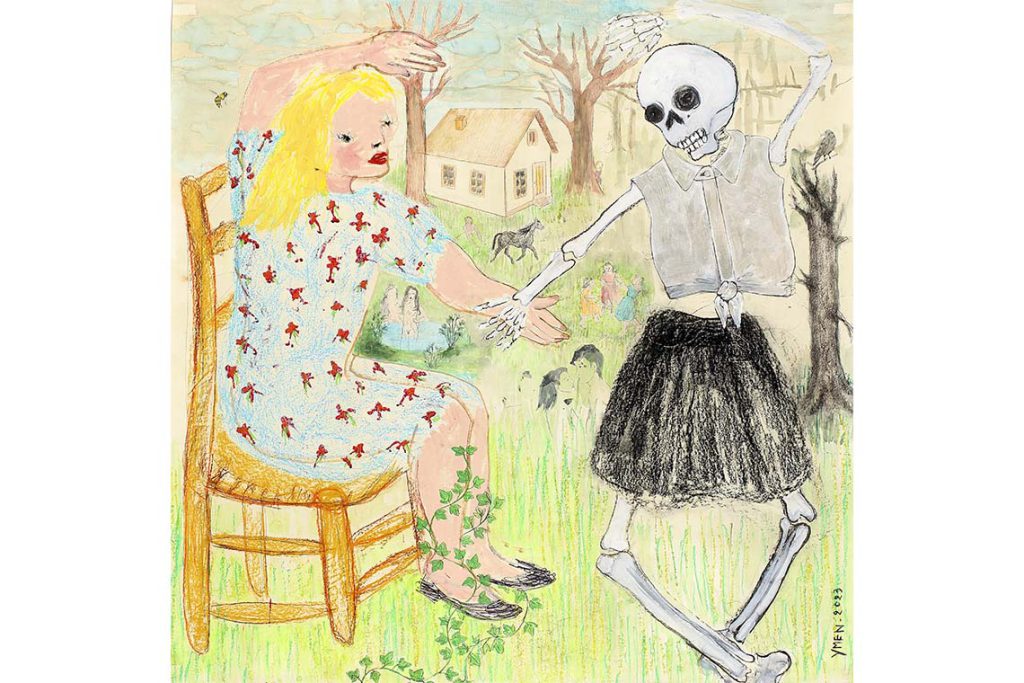

Ymen Berhouma: After 20 years of practicing, I now find a lot of freedom in it. Whether I’m painting or drawing, I’ve found that certain aspects of my work tend to recur. That said, I enjoy the element of surprise in what I do – there’s a freshness to it that perhaps comes from being self-taught. My latest drawings really tap into this. I am filling the paper with whatever images and characters come to mind – it could be a child holding a doll, a cat, a house set on fire… These elements superimpose themselves to create an unintended visual narrative with a storybook quality to it.

The subject matter of your work seems to have shifted in recent years to include multiple scenes involving characters in sometimes incongruous or dark situations, as with Vivre est un village où j’ai mal rêvé (2023). What has changed for you as an artist?

I switched to drawing a few years ago after a personal event forced me to work from home for a year or so, since when I’ve been working with paper and drawing. I also started paying more attention to world news, which I had consciously avoided before so as not to influence my art. Perhaps some of the darkness comes from there, but most of these scenes are really emerging from my interior world. I think this is when I started making what I would call “contemporary” art, as it was based on the present moment.

Do the more fantastical elements in your work come from particular stories or fables, or are they sparked by your imagination?

They come from the act of drawing itself. I start my work with an abstracted shape, which probably links to an unconscious act of naivety, one of simply drawing things as they come to me. I cherish literature, which has a great influence on me, and I read a lot in my year of solitude. Films inspire me, too. I’ve recently started giving titles to my works, perhaps in an attempt to grasp the content. My practice allows me to know myself better, as it is an intimate exchange that evolves naturally.

So your work is a form of visual diary?

Yes, it is. It came out of the need to fill my time while I led a life removed from other people. I started with the intention of creating one drawing for each month of the year, which became two per month as I realised how quickly I was completing them. There were 24 drawings in the exhibition last year at A.Gorgi Gallery called 3K900, which was the weight of the drawings.

How do you know when a drawing is finished?

My main issue with the work is not so much the theme, but the composition. When I begin a drawing with abstraction, it’s an intense process during which sometimes I even hold my breath as I start drawing, but I always know which part of the paper I am aiming for. It’s different to painting, where I was so into the details that I knew a work was finished when I had completed all of them. I am freer when drawing, the work is more frank, more real and closer to who I am, while always being tied to this idea of storytelling.

Can you explain some of the animal symbols that you use in your work?

The animals impose themselves unconsciously in my drawings. I have become fascinated by snakes after I started drawing eels. I’m interested in the idea of their being difficult to grasp, and in the French expression avaler des couleuvres, which technically means to swallow grass snakes but is used idiomatically to reference someone who believes anything they are told – hence the snake coming out of the woman’s mouth in A moment before the great anger (2024).

How do you feel about being referred to as a Tunisian artist, with the implication of being part of that broader art scene?

I feel a lot of freedom in it, while also rejecting the idea that we need to qualify types of art based on where they come from. I am Tunisian, therefore my art is. But whether or not my art looks particularly Tunisian is not something I am concerned with. In today’s world, I find this way of seeing things rather limiting. I’ve always tried to express myself in my art, to have aesthetic freedom. I guess that is typically Tunisian. The small size of the art scene in Tunisia can be a hindrance, but it’s also an advantage in the sense that it allows more direct access to certain things. I set up a non-profit artists collective in Tunis called Atelier Ymen, which primarily organises exhibitions by emerging artists. Because I have a few more connections than some early career artists, I try to help them and I’ve seen a lot of collectors visit the shows regularly to acquire work. Some gallerists also come to discover new talents.

Do you feel part of the wider art scene across the Maghreb?

I tend to operate in quite a solitary fashion, but I do work with my gallery A.Gorgi and have taken part in Investec Cape Town for the last few years. I love Morocco, where I have many artist friends, and am inspired by people like Hassan Hajjaj and Mahi Binebine. I do consider myself completely Maghrebi. I find contemporary art from the Global South, and in this instance the Maghreb, perhaps more interesting than in the Northern Hemisphere. It is less polluted by the art market and retains a certain sincerity.

What does the future hold for your art practice?

I will continue drawing, but want to start painting again with everything I’ve learnt in the past few years. I’ve always kept notebooks, so I have the idea of creating a form of artist book, a graphic journal or diary of the last decade, which will evolve alongside my drawing.

This interview first appeared in Canvas 117: The Maghreb Issue