Standing by the ruins, Dana Awartani’s first institutional solo exhibition in Europe at Bristol’s Arnolfini, is a moving and timely exploration of how acts of repair can counteract the destruction of cultural heritage.

Tucked away on the third floor of Arnolfini in Bristol, right on the former docks overlooking a Coyote Saloon on the other side of the river, is Dana Awartani’s latest solo exhibition, Standing by the ruins.

The show is a small but neat affair, with three rooms displaying some of the Saudi-Palestinian artist’s most celebrated works as well as a new commission. The first room sits on the side overlooking the river, but you wouldn’t know this immediately as the windows are covered by sheets of black fabric, pulling the focus inward and away from the distractions of the outside world.

The concept is simple, yet effective. Throughout Arnolfini, contemplation appears to be the name of the game, with yoga mats hung on walls all over the building, encouraging visitors to take a moment to relax and breathe. A bench against one of the far walls of this first room provides a similar opportunity. I found myself losing track of time as I sat gazing upon Awartani’s reconstructions in Standing by the ruins III (2025), a set of three large square sections of tiles displayed on the floor of the first room. The patterns are derived from images of the floor of one of Gaza’s oldest bathhouses, Hamam al-Sammara, which was destroyed in the relentless bombardments by the Israeli army over the past two years. Around the walls are sketches of the patterns found in the tiles, meticulously charting and reimagining what once was.

The tiles, handmade by Awartani and expert craftsmen from Riyadh with knowledge of adobe earth restoration, are broken, cracks appearing throughout, seemingly worn by time, or smashed with a large hammer – as though demonstrating that, even when the tiles are put back together, the scars remain. Sitting in this room, the noise of the gallery and the world beyond it fades away. We imagine ourselves in Gaza, in this bathhouse, present since the fourteenth century, which has witnessed so many changes, eventually succumbing to one of the land’s darkest chapters in its history.

In the second room, we zoom out of Gaza and Palestine to enter the focal point of the exhibition, Awartani’s monumental Come let me heal your wounds. Let me mend your broken bones. (2024). A follow-on from an initial project, Let me mend your broken bones, it recreates a map of the so-called ‘Middle East’ through sheaths of hanging translucent fabric.

Although it has been displayed many times before, most recently at the last Venice Biennale, the effect on a first-time viewer such as myself remains just as impactful. On each piece of fabric, representing a country in the region, small rips have been made at sites where cultural heritage has been lost or destroyed in the wake of the Arab Spring. Some countries have more wounds than others, but these have been carefully stitched together by hand, an act of repair that marks and scars the delicate fabric and is dyed using traditional Ayurvedic techniques with medicinal properties.

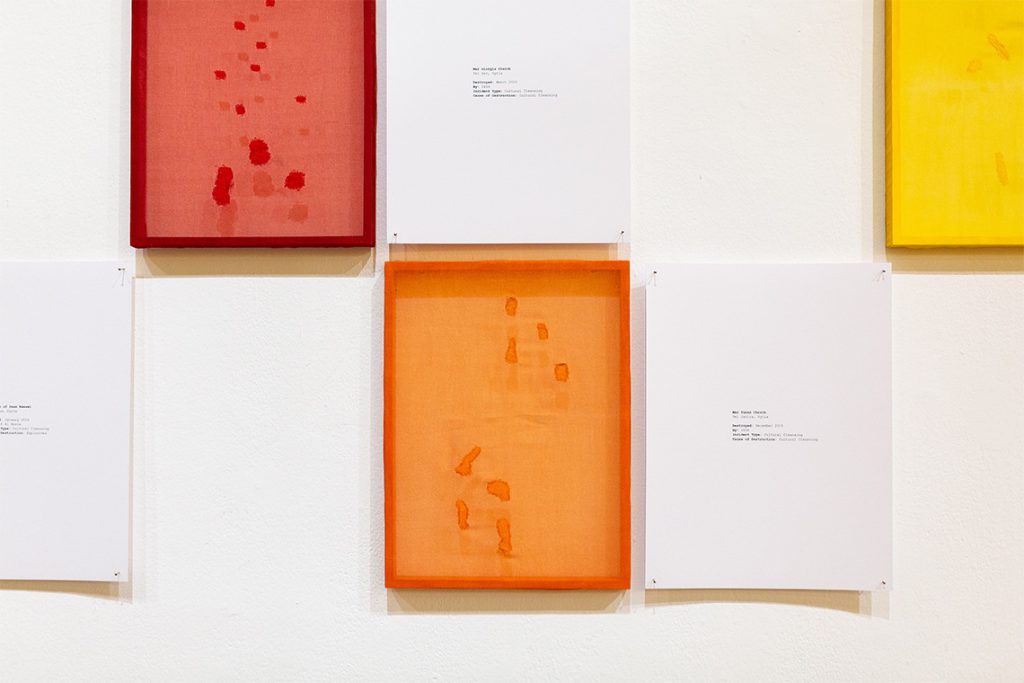

The work is intrinsically impressive in its scale, hanging diagonally across a large room and measuring over ten metres at its widest point. The central work is surrounded by smaller pieces, from the ongoing series Let me mend your broken bones (2023–), which are hung on the walls of the gallery space. These individual pieces of transparent fabric in frames, each with the same careful stitching, represent various locations across Syria where heritage sites have been destroyed. The white paper next to each details exactly what, where, when, by whom, what motivation and by what means, detailing a never-ending cycle of ruination. It is impossible not to be moved, whether by the intention of Awartani’s careful darning of the fabric or the feeling that the wounds of the region continue to open up today. Perhaps there are now too many to stitch back up, although Awartani may try.

Image courtesy of the artist and Lisson Gallery

The final room brings us face to face with the artist for the first time, in the video and installation work I Went Away and Forgot You. A While Ago I Remembered. I Remembered I’d Forgotten You. I Was Dreaming. (2019). Here, Awartani sweeps up tiles made of sand, created in a traditional Islamic geometric pattern in a house in Jeddah, while underneath, a more modern pattern of tiles is revealed. The tale of loss here is more overt, as we see clearly how easily cultural heritage is destroyed. In the gallery, the same tile pattern has been meticulously recreated in sand for the exhibition.

There is a cruel concluding sadness in the idea that, as time-consuming as this recreation is, it can all be swept up in one fell swoop. It echoes the rapid destruction of history and culture across the region, a heritage built over many hundreds if not thousands of years, and destroyed in an instant. Perhaps for Awartani, the ability to adapt to destruction is a form of resistance in itself, signalling the capacity to rebuild and mend in any place, in any form, whether at the actual place of destruction or in a gallery in Bristol.