For this year’s edition of Art Basel Paris, galleries from the Middle East and North Africa revealed a set of practices that were intellectually rigorous and materially experimental. Among the most compelling presentations were those of Marfa’ Projects (Beirut), ATHR Gallery (Jeddah) and Selma Feriani Gallery (Tunis/London).

An inward turn has defined many of the offerings at Art Basel Paris this year. The domestic sphere appears as a charged terrain through which artists examine desire, the permeability of social and political boundaries, and the negotiation between inherited forms and shifting subjectivities. A move from universal narratives toward lived texture is accompanied by attentiveness to materiality. Across the fair, artists are drawing on fragile, humble and unconventional substances to think through the relationships between body, object and habitat.

Marfa’ Projects’ presentation articulates fragility as a structural condition. Founded by Joumana Asseily, the gallery has long animated Beirut’s independent art scene, sustaining experimental practices that flow from the city’s charged conditions. The works on view by Mohamad Abdouni, Ahmad Ghossein, Caline Aoun, Tamara Al-Samerraei, Majd Abdel Hamid and Paola Yacoub share a sensitivity to residue and repair. Time-bearing substances – threads, soap, aluminium, resin, fabric and plaster – are carriers of personal and collective narratives; they record pressure, absorb crisis and eventually erode.

Mohamad Abdouni’s sculptural series Soft Skills (2024) addresses fragility through the social scripts that shaped his boyhood, the pressure to inhabit hardened forms of masculinity within Lebanese domestic life. Cast in aluminium and resin, his subversive figurines recall the pastel-glazed ornaments that populated living rooms in the late twentieth century. By returning to the décor of the home, the first stage on which gender is recognised, Abdouni uses nostalgia as a site from which to unpick how masculinity is performed, repeated and naturalised. His figures, drawn from recollections of youth in the Bekaa Valley, inhabit scenes where intimacy, insecurity and play sit side-by-side. Their gestures, sometimes tender, sometimes provocative, chart masculinity as a rehearsed performance rather than an inherent state. The industrial weight of aluminium and resin is finished to an iridescent, porcelain-like delicacy, heightening the tension between endurance and affect. Through his translations of retro domesticity, Abdouni affords the familiar political voltage, opening room for emotion, humour and counter-imaginaries of boyhood within terrain once reserved for conformity.

From the staging of interior worlds, the curation pivots toward the material registers of crisis in plain sight; Ahmad Ghossein’s installation, A Sealed Gallon (2023), pushes forward the aesthetics of collective struggle in Lebanon. Three translucent bottles, cast in acid-green and brown resin, beside a coiled copper hose, recall the improvised tools used to siphon petrol during Lebanon’s 2020 fuel crisis. The work channels the sensorial language of scarcity. In monumentalising disposable containers, Ghossein exposes the practical and ethical tensions of crisis – how survival devices become the recognisable traces of corruption and a suspended economy.

Paola Yacoub’s (1995) reliefs, moulded from bullet holes along Beirut’s Green Line, extend this material enquiry into time. Trained in architecture and experienced in archaeological fieldwork, Yacoub approaches her city as a record in motion. Her casts, produced from hardwood paste, register traces of impact without assigning causality. She evokes the idea of the built environment as a scar – a surface that, like skin, absorbs trauma, expresses and endures it. Yacoub’s use of organic materials preserves the shock of destruction while also allowing tenderness into the work. Her attention to the ephemeral has echoes in post-war artistic practices that used rubble, debris and ash to think through disappearance, but in Beirut, such materials refer to conditions still unfolding.

Close by, ATHR Gallery presents a generational vision through the work of three Saudi women artists born in the 1990s: Sarah Abu Abdallah, Hayfa Algwaiz and Lulua Alyahya. Their emergence follows the earlier impact of Manal Al Dowayan and Lulwah Al Homoud, artists who opened conceptual space for female authorship in Saudi art through their respective languages of social commentary and abstraction. This cohort inhabits a distinct moment shaped by reform, global connectivity and the digital mediation of identity. Their works reveal divergent but complementary lines of reflection: Algwaiz interrogates conditions of visibility; Abu Abdallah assembles the debris of everyday life into new syntaxes; Alyahya turns inward, shifting between day-to-day encounters and dreams.

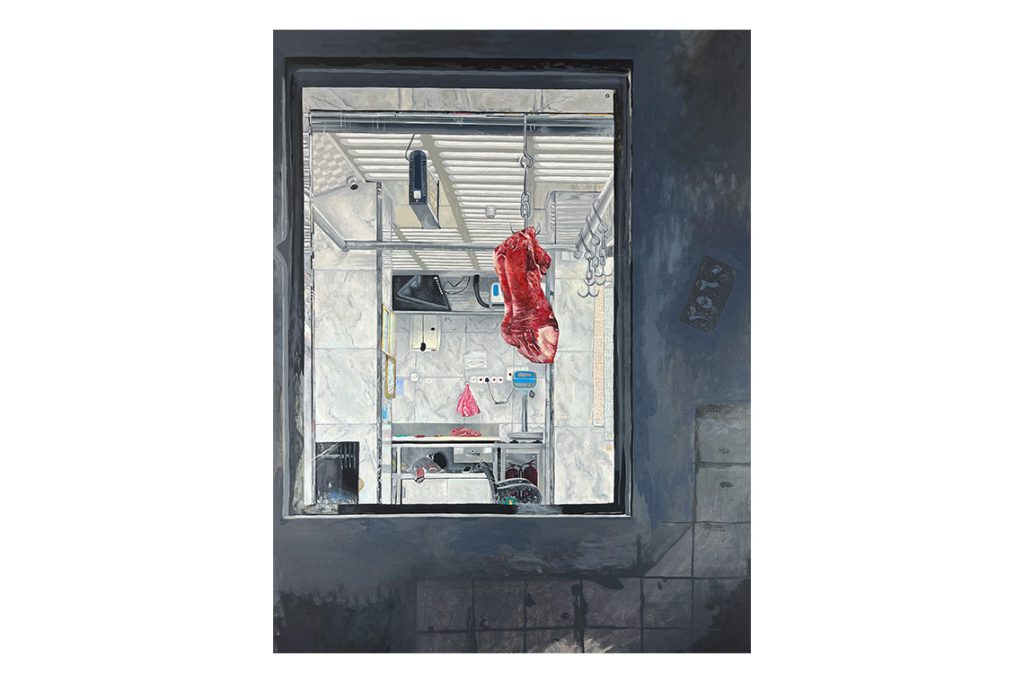

Hayfa Algwaiz’s paintings manifest anxieties over spectatorship through the architecture of the image. Her compositions are characterised by close cropping and controlled perspective, where the body is noted through its absence or partiality. A particularly evocative piece in the backroom is A Woman’s Body (2025). Here, a fleshy, female torso hangs from a butcher’s hook against a backdrop of muted grey tiles, an image that echoes Francis Bacon’s Figure with Meat (1954). The artist positions the viewer outside the butcher’s shop, looking in through a pane of glass. The act of spectatorship is factored into the logic of the painting. Algwaiz transforms spatial order into psychological tension; the sterile geometry of tiles, the surveillance camera above, and the suspended flesh all expose how visibility functions as discipline.

Algwaiz probes the mechanics of spectatorship through realism, while in Alyahya’s work, perception loosens. Indebted to the codes of surrealism and cinema, her paintings deploy framing, pacing and atmosphere to produce a psychological charge in which figures drawn from ordinary life feel at once present and withdrawn. Among her portraits of reclining men, a standout piece is Untitled (2025). A central figure in a thobe lies beneath the floating image of a woman stroking her puppy, an apparition hovering like a projection in the dark. Familiar domesticity and estrangement coexist; the resting body moors the scene while the suspended image slips past it, unsettling the line between lived reality and interior projection. Alyahya’s muted palette and diffused light heighten this drift. Rest, as a metaphor, recurs in her art, allowing the everyday to fade and other possible worlds to cohere. The gendered inversion is also notable here – a female painter turns the male body into the site of speculation, reversing the traditional direction of the gaze without forcing it as a theme.

Where ATHR coheres around a gendered and generational lens, Selma Feriani has opted for multiplicity, bringing together works by Zineb Sedira, Monia Ben Hamouda, Nidhal Chamekh, Nadia Ayari, Yann Lacroix and Aymen Mbarki. The diversity of media – sketches, paintings, sculpture and lightbox – allows for a field of enquiry that traverses personal desire, ritual gesture, postcolonial reflection and material experimentation. Convergence and dissonance hold a delicate balance here.

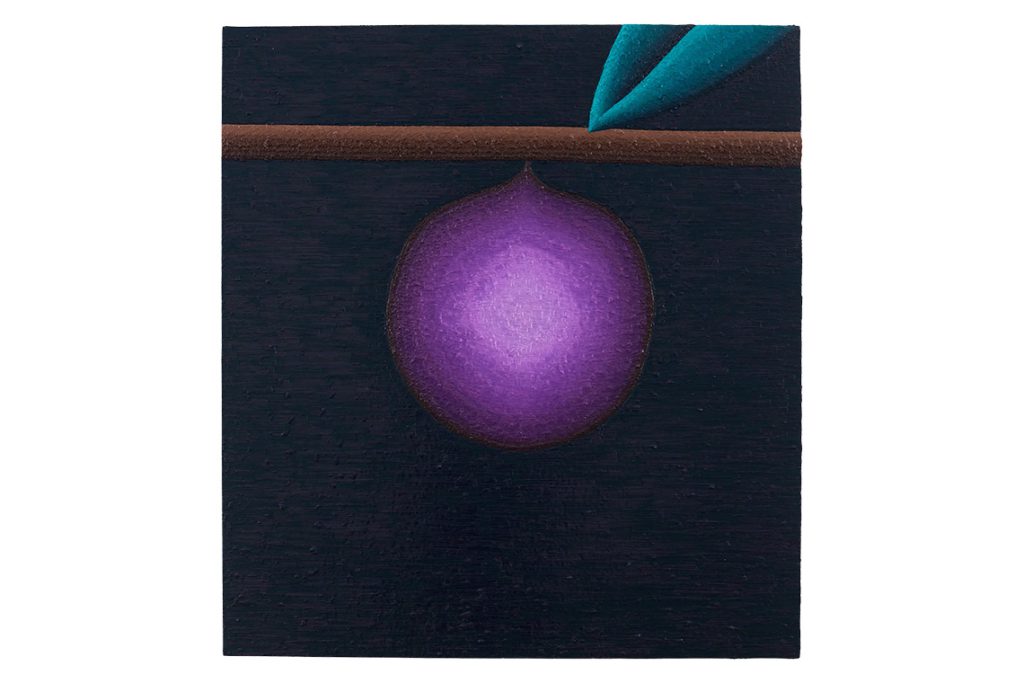

Within this constellation, Tunisian-American painter Nadia Ayari’s Safe Word and Tight (2016) stands out for their sumptuous meditation on submission, restraint and the politics of form. Ayari’s paintings from this period drift between abstraction and narration, centring vegetal motifs. A fig, branch and leaf are suspended in darkness, rippling as dense fields of plum, turquoise and brown. The fig captures multiple meanings, from its sensual and biblical associations with fertility and concealment to its contemporary readings as a metaphor for gendered visibility. Ayari renders it as a luminous sphere, at once ripe and sealed, its surface smooth yet quivering at the edges. Through layered oil that catches the light, she transforms the fruit into an emblem of controlled desire. The painting’s tactile density mirrors its conceptual tension: seduction contained within structure, impermanence captured through precision.

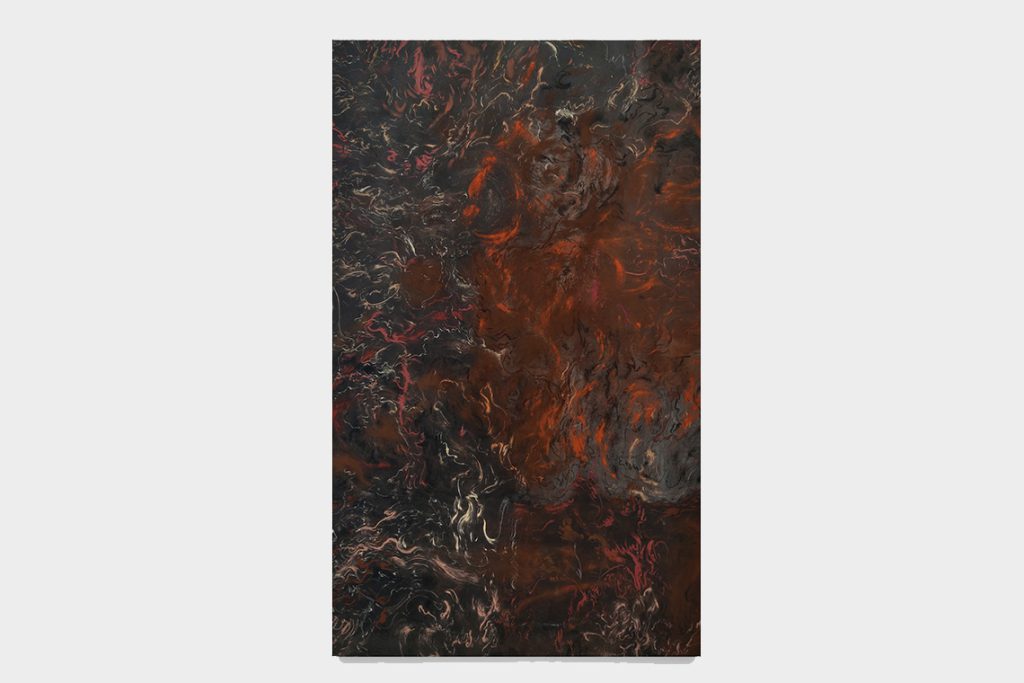

Monia Ben Hamouda approaches ideas of containment and release through her own material logic. Working with charred steel, cloth, earth pigments and spices, she enacts what she has termed a “shamanic” process – a way of reconnecting with, and contesting, the cultural legacies of her Muslim background. In her new large-scale painting, A Burst of Light IV (2025), gesture functions as exorcism, with heat, abrasion and layering performing a ritual undoing of expectation. Her richly textured surfaces, swirling, burnt and marked, carry cultural lineage but break from it within the same frame.

Ayari and Ben Hamouda toy with symbolism and ritual, but Nidhal Chamekh’s offering is overt. His Frictions (2024) series stages collisions between Greco-Roman statuary and West African masks, creating hybrid physiognomies that unsettle the conventions of classical form and exhibition. In the works presented here, wood and marble meet through clean incisions, their contact points exposed. The tension arises from what is rarely seen together: two aesthetic systems that Western taxonomy has long kept apart. The resulting faces feel both continuous and fragmented, their unease magnified within the fair context, where clarity of authorship and category are prized. Drawing on Édouard Glissant’s concept of relation, Chamekh reimagines hybridity as a state of productive opacity, an encounter that resists hierarchy while insisting on interdependence. It is work that confronts, reminding us that history is an unstable terrain of control and collision.

Across these presentations, artists are working from lived worlds rather than the panoramic frames that typically organise fair discourse. Close range yields a distinct material logic – modest media carries dense histories, small forms enclose structural pressures and fragile substances bear conditions that far exceed their scale. The emphasis lies on proximate habitats and inward states, on how gendered expectations, domestic, ritual and colonial forms continue to ripple through the present at the level of surface and affect. An attentiveness to the physical traces by which legacies remain legible runs through the works: the domestic residue of Beirut, the architectures of spectatorship in Saudi Arabia, the ritual negotiation of lineage and the inherited collisions of classical and colonial taxonomies. Each of these positions asserts that the present is apprehended through surfaces and structures still bearing historical weight.