The exhibition Landscapes at Karma in New York presents work by the late Iranian-American artist Manoucher Yektai, who after arriving in the city in the 1950s, forged a practice which in many ways defied his peers’ refusal of romantic figuration.

Manoucher Yektai sailed away from Iran in the 1940s, heading for Paris to study the Post-Impressionists, particularly Cézanne. After a series of unexpected stops and diversions, the ship on which he was travelling eventually took him not to the French capital but to Los Angeles, where the young painter and poet embarked on a cross-country train ride to New York City. There, the kings of Abstract Expressionism were starting to rule the town, but Yektai’s mind was still preoccupied with the Fauvists and Cézanne. The year-long odyssey finally brought him to Paris a few months later, and he enrolled at the École des Beaux- Arts and began frequenting André Lhote’s studio. During a café break one day near the Sorbonne, he looked around the Latin Quarter to realise that his dream city was in fact living in the past – the centre had already shifted to the other side of the Atlantic. It was 1948, and soon Yektai was back in New York to study at the Art Students League.

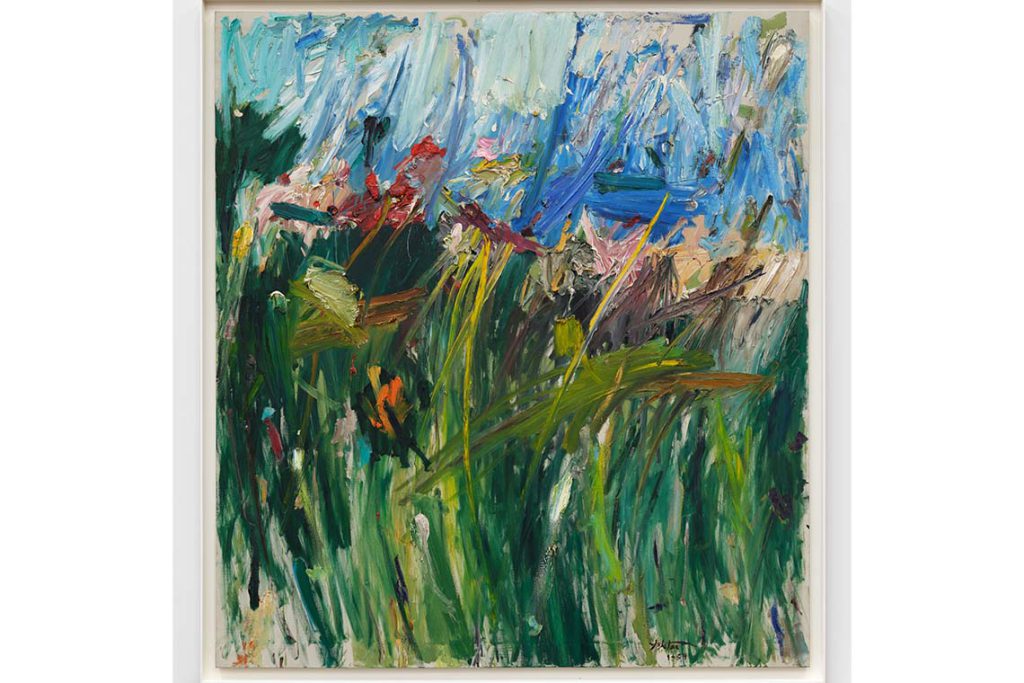

The traits of a life honed by drift never left Yektai’s paintings. The works in Karma’s Landscapes show are bookended by 1956 and 1992, marking the decades during which the artist was steadily productive with his canvas. Besides views of around his Manhattan studio, the paintings depict sceneries from upstate New York, Vermont, Long Island and even Positano. Sharp gestures come and go in the blink of an eye, like the insistent rain drops of autumn. Their accumulations bear landscapes of remembrance vehemently ingrained into their surfaces, but they somehow also convey transformation and mobility.

Among his peers like Jackson Pollock, Sam Francis and Willem de Kooning, Yektai came into success as an odd card. He was darker, with an accent from a place where almost no one was from, and perhaps most strikingly, during his colleagues’ law-abiding commitment to non-figuration, Yektai painted semi- places. With a desire to never abandon his first love, he infused into his sceneries a hint of Bonnard, Matisse or Cézanne.

Landscape of Italy (1958) contains blows of green from all corners. The crescendoed prolificacy of a man at 37 is felt with his powerful grasp on the energy of his remaining years of youth. Amidst the green profusion, a faint semblance of a human figure moves towards the canvas’s upper blue marks. Mid-journey, the character looks engulfed in the surrounding landscape and the walk he has committed to. Another untitled painting from the same year almost entirely dedicates its real estate to Earth, with a wave of blades of grass wildly protruding from the soil towards a thin layer of sky.

In a captivating palette, the paintings traverse the realms of stark figuration and almost abstraction. Yektai’s colours are in fact the most striking shade of each hue, as if his effort was to monumentalise a place forever in the most vivid memory possible, yet in his very own terms. Across a span of representing a place and its fluid remembrance, Yektai humanises the picture, rendering a land stomped a billion times by others his very own.

Take 95th Street Landscape (1958), which suggests that Yektai was looking out of the window at his uptown studio. Romantic pastels and patches of green and yellow conjure an operatic rhythm with rapid gestures, complicating the expectation of the see-saw Manhattan silhouette. Instead, a plethora of powdery hues occupies the generous portion of the horizontal frame, devoid of any faint architectural greyness.

Yektai’s paintings internalise the complex feeling of belonging to a place with a subjectivity innate to poetry. This was perhaps among the reasons why he never translated his poems from Farsi to English – the landscapes handled the cross-linguistic message. Those who never visited the titular upstate New York town will not get a gist of its visual fabric from Saratoga Landscape (1959). Instead, they encounter a blazing panorama of colour and memory, seeped through the physicality of being there. Kaleidoscopic, the brushstrokes dissolve the tactility of inhabiting a landscape with explosive marks. The composition also solidifies the mercurial feel of an afterthought, the taste left behind after a stroll in nature and the breeze rubbing the face.