The artist delves into histories through the alchemy of memory and explains how cynical curiosity continues to define his practice.

Written history, in many ways, is an unreliable source. Penned predominantly by the victor and systemically disseminated to self-serve, the one-sided narrative between the glorified and the disgraced documents the past through a flawed lens. A sharp division between the proclaimed winner and the supposed fallen too often fails to understand the present. Adel Abidin’s inquisitive relationship with history establishes the foundation of his multidisciplinary practice. In fact, the opaque dynamic between the chronicler and the defeated has baffled the Iraqi-Finnish artist from a young age.

Abidin was 21 when he first read about the Zanj Rebellion through Faisal Al-Samer’s 1971-dated eponymous book. The story of enslaved salt-collecting Africans rebelling against the Abbasid Empire 1155 years ago was a sign of history’s circular nature, as well as the unending human urge for governance. “I was surprised to learn how the Abbasids were using slave labour from Africa in the 860s to make the wealthy wealthier,” he tells Canvas. He has lived “subconsciously” with the story of the fourteen-year-long bloody battle ever since, but it took three decades before he felt the time was right to explore the Zanj revolt in his practice. He proposed a work to the Ithra Art Prize last year and won.

ON (2023) – a mammoth mural of ink abstractions on Japanese paper – was selected by the jury from more than 10,000 entries for its piercingly subjective illustration of history’s gnarly workings through the story of the Zanj revolt. “As I delved into more research, I started noticing how many elements don’t fully make sense because the victor writes most of the events,” explains Abidin, who was struck by the lack of the perspective of the Zanj people in any of the texts. “History reaches us as modified, with some of the facts being exaggerated or fabricated over time,” he adds. After unveiling ON at Ithra’s Great Hall last autumn, the artist embarked on a multidisciplinary exploration of the historic rebellion, presented in a way which he describes as in “multiple chapters”.

One chapter comprised his solo exhibition The Revolt, presented at Helsinki’s Forum Box Gallery earlier this year. Abidin decided to suggest an unexplored telling of the Zanj people. “My point of view on the subject was to talk through the eyes of the resistance,” he says, “because all the books had been written by the Abbasids.” The show unfolded through three artworks to both materialize the uprising and crystallise its uncharted dynamics for the contemporary public. Unmatched Narratives (2024) included a suite of ink drawings constructed like sketchbooks in metal frames with mirrors in lieu of some of its pages. Blotched abstractions in black dominated the pure white blank pages; the mirrors radiated drawings of bodily figures and Arabic texts, yielding a malleable account of the event through a multitude of angles.

Whether paper or salt, each material enables Abidin to reach his conceptual end rather than dictating the trajectory of his practice: “I never consider the medium as the essential part.” He instead “listens the idea” to hear what materials to pursue. Moving image, for example, constituted the show’s third work. In the four-minute long single channel video, Saline Lands (2024), the camera roamed around piles of salt in current-day Basra – between the coarse puffiness, a pair of toy legs stomped the pungent land in trace of dissolved stories. Humour intrigues the audience while navigating his storyline. “I want people to think and even argue with me,” he says, “and laughter can provoke thought.” Not unlike his materials, humour emerges organically, “not forced, but as the right solution for the concept.”

Adel Abidin. The Message. 2023. Video still. Image courtesy of the artist

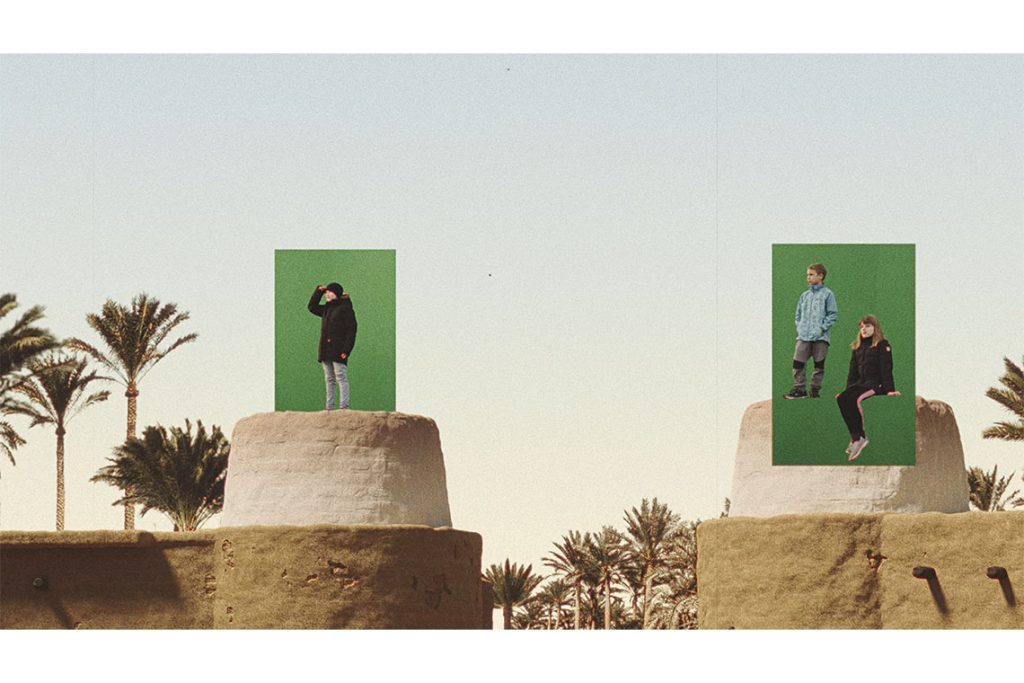

From the untreated curiosity of childhood to maturity’s intentional sarcasm, whimsy seeps into Abidin’s practice, often through his own memories of the yesteryear. The Message (2023) is an almost three-minute video in which children reenact scenes from Abidin’s favourite film, the Syrian director Mustafa Al-Akad’s 1976 The Message, about the life of the Prophet Muhammed (PBUH). Abidin was fascinated as a child by the film’s swift transitions between English and Arabic. “I was always so excited by the Prophet’s arrival in Medina and the way he is greeted by his followers,” he remembers. He finds a similarly honest excitement in the children of today towards the offerings of technology, such as TikTok or video games. He has therefore turned his “magnifying glass” no further than his own childhood thrill and the current juvenile amusements. The video’s group of children stand in front of a green screen with three dimensional renderings of the film’s arrival sequence. Their immediate response is akin to that of the Prophet’s followers, but a drone hovers above the artificial sacred encounter – a curious avian in metal and wire peeps into the raw reactions with its engineered omnipresence.

Between unveiling history’s overlooked voices and illustrating a poetic inquiry of the present, Abidin summons the promise of storytelling. Whether in film, drawing or sculpture, he visualises a balance between reality and imagination. A background in painting helps him mediate his visions, including illustrations of storyboards for video works. Abidin quit painting in 2003, three years after he completed his bachelor’s degree at the Academy of Fine Arts in Baghdad. The decision to veer away from the easel came out of an urge to “do more than two dimensions on a wall and go deeper with my ideas”.

A marriage initially brought him to the Finnish capital 23 years ago, after he had already received his degree in painting from the Academy of Fine Arts in Baghdad. Over the years, he also built another connection with Amman, where his parents moved after the Iraq War – he even opened a second studio in the Jordanian capital. The mixed-media installation Plan B (2007) explores this intricate and exhausting search for a home in the face of terror. A 14-minute video shows Abidin covering the sharp objects and debris at a sawmill with mattresses. The artist’s efforts to cushion a rough environment are elevated with a layout of actual mattresses at the exhibition space, where domestic familiarity intervenes into the pristine white cube, not unlike the video’s depiction of Abidin’s attempt at healing through softness. The year he exhibited the work at the Val-de- Marne Contemporary Art Museum in Paris he also obtained his degree in time and space art from the Academy of Fine Arts in Helsinki, which led to an epiphany of material freedom, whether salt or mattresses: “I follow my gut feeling about what medium the work needs to be in, sometimes sculpting or painting.”

Regardless of a medium or a reference point, curiosity fuels Abidin’s creative pursuits. “I keep a child-like eye on the world,” he says, admitting that “I perhaps have a raw lens, looking at my surroundings without analysing them.” This instinctive approach leads to witnessing life “take shape in front of me without all the readings”. Candidly absorbing the equilibrium provides the artist with a blank canvas on which to grasp it with his own experience and knowledge. Through this approach, he seeks to “consciously shape the starting point”.

Tire (2024), a resin sculpture of an inverted car tyre, captures the alchemy between the mundane and the internalised. For 12 years Abidin had dabbled with the idea of flipping an actual tyre, and he eventually fully sculpted the object from scratch. Economic in form, the tyre intrigues him for its effortless connotation of movement, “a symbol of going from A to B” On a grander outlook, however, there is a nod to mobility – of people, of time and of ideas – supposedly moving ahead, but in reality in a rather more chaotic order. “While we seek for the future or going back into the past, there is a movement, but the inside is out and the outside is in,” he observes.