Through twisted myths and smirking faces, Ali Elmacı’s paintings illustrate social conundrums with bold-coloured humour.

Owl-eyed gazes beam like headlights on a dark highway; massive smiles grin as big as caves out from which bats could fly. In Ali Elmacı’s vibrant paintings, erratic figures with childish enthusiasm face hyperbolic scenarios – think banana attacks, chihuahua bites or gruesome picnics. Colours burst and landscapes pop.

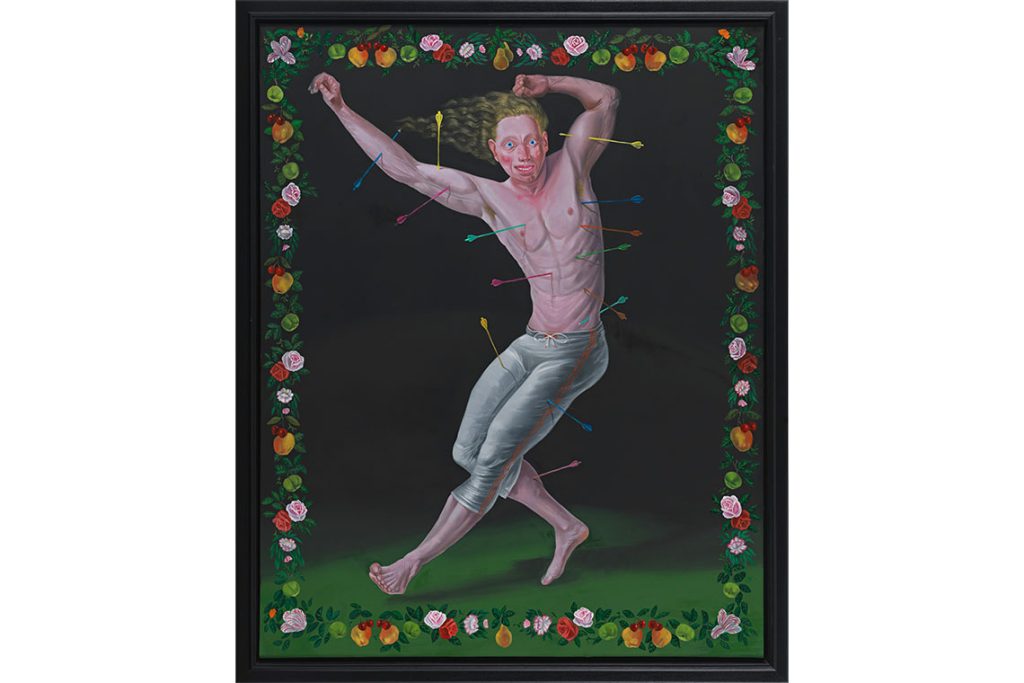

The Istanbul-based artist’s paintings of pink-skinned characters are energised by an anarchist euphoria, a pop absurdism that blends the MTV-speed of contemporary life with tragedies comparable to the gargantuan plot twists in Greek mythology. Some nude and others dressed in modern life’s familiarity, Elmacı’s figures occupy a cinematic space – there are grand gestures and glorious lighting. “I tackle serious or even heavy subjects in my paintings, so I try not to be too didactic,” he explains. “Humour is a great way of softening my statements.” Behind their unabashed absurdism, his vignettes satirise dynamics that are skewed by authorities, collective hypocrisies and the epidemic of numbness towards injustices. Veiled by a cartoonish approach to figuration, such sociopolitical topics are coloured by heavy make-up and hilarious narratives, yet like a drag queen’s witty number, the lustre only makes the punchline more piercing.

In his solo exhibition, Kiss My Lips, Dagger My Heart, at Istanbul’s Pilevneli gallery earlier this year, the artist summoned cues from Spaghetti Westerns, overflown news content, social media cacophony and the canonised Western art history. A series of portraits show posey cowboys and frilly underwear-donning Southern belles, their sharp hypnotised gazes locked on our eyes. We cannot look away from the excessive joy on their shiny faces. Elmacı adds to the paintings a sculptural layer with shotguns framing each canvas. Like haunting objects at a thrift store, they creep into our contemporary logic and poke at our need for a rest. The artist named the portraits Şiddetin Ne Hoş Ne Güzel Şefkatin (How Nice Is Your Violence How Beautiful Your Compassion) (2022–23), based on a line from a popular 1990s Turkish pop song.

Gaze and nostalgia are indeed formative traits for Elmacı, who was born in a small village near the northern Turkish city of Sinop in 1976. He moved to Istanbul right after high school and after a decade of working at odd jobs, he enrolled in Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University’s painting department in 2004. The highly academic formal education reminded him why he liked to paint in the first place. “I already had drawn a path in front of me, because I was painting as a child before I could read or write,” he recalls. Circumstances had delayed his art education, but he knew that painting was his way out. “I have been thinking about why I am so obsessed with large gazing eyes in my work,” he admits. The artist has lately come up with two explanations: “Like every child in Türkiye, I grew up with the picture of Atatürk in my classroom staring down at us and there was always a picture of my older brother in our living room because he was always away – these two eyes always followed me.” He considers the figures somewhat as auto-portraits because the eyes are mostly based on his own.

In one of the show’s many eponymous paintings, titled Kiss My Lips, Dagger My Heart IX (2022), a blond woman lies on the grass with an expression which could have been considered ‘terrified’ in any other artist’s painting. In Elmacı’s universe, however, her impression is commonplace, an over-the-top smirk contoured by a makeup veneer. A bunch of chihuahuas are nibbling on her skin while she is frozen between helplessness and pleasure – she lets the canines do the chewing; she pretends it hurts or fakes the joy.

Elmacı’s recipe for concocting the right dosage of narrative absurdity and optic abundance is to begin with a cause. “I always start with issues that bother me,” he explains about his approach to a blank canvas, “because whatever I find troublesome around me, I want to turn that into a painting.” An observant of shaky social equilibria, political turbulences and cultural shifts – as well as our blindness for all – Elmacı crafts oil-on-canvas juxtapositions staged like film stills or family portraits. Oscillating between technicolour nightmares and B-movie boundlessness, his paintings communicate with the viewer through their twisted abundance. Bright colours, theatrical gestures and heavenly backgrounds mingle and eventually explode into kaleidoscopic limbos.

In three paintings, each titled Kendini Sıcakta Beni Soğukta Tut (Keep Yourself Hot Keep Me Cool) (all 2021), a melon, a watermelon and a pumpkin each receive their self-portraits with eyes and mouths carved by sharp knives. A lush, otherworldly nature backdrops each setting: the landscapes explode with sharp sunlight, pastel pink roses and gushing waterfalls. On the forefront, the fruits have visages carved into solemnity. The watermelon’s red inner renders a pouty expression; the melon’s deadpan stare seems indifferent to the beautiful rose next to the crop.

Elmacı has been working at the same studio for the last 12 years in the Yeldeğirmeni neighbourhood of Istanbul’s Kadıköy district. “I find peace being at the studio,” he says about his 75-square-metre refuge with its five-metre high ceilings. He usually shows up in the afternoon and makes sure to spend at least eight hours there, occasionally staying until dawn breaks, while listening to rock music or having an old TV shows or film run in the background for white noise. He starts every painting with a photograph for which his friends and colleagues sit in outfits in which he dresses them. The posers reenact narratives the artist pens before starting to paint. “I first paint the figures without any specific gender or age,” he explains about his early steps, “but I rather focus on what kind of authority each character has within the setting.” The photographic quality of the paintings imbues them with an energy on the brink of an explosion: both protagonists and antagonists, they fill in multiple roles of the hero, the villain and the Greek chorus.

St Sebastian is an icon to whom Elmacı constantly returns in his oeuvre. His last show had two versions of the ill-fated Christian saint, who has been depicted throughout Western art history as a victim in the hands of pagans. In the artist’s take, the young man is neither tied to a tree nor gets penetrated by any merciless arrows. Dancing freely in blue Adidas briefs in one painting, which is titled after the show, the hunky blond saint stretches upwards like a ballerina while bananas gently poke his muscular body. “My Sebastians are manipulative,” Elmacı says, turning the myth upside down. “Rather than being real victims of authority, they are ‘playing’ the victim while they are attacked by candies or bananas, and they have no wounds,” he concludes.

This profile first appeared in Canvas 109: Smoke and Mirrors