Dislocations, currently showing at the Palais de Tokyo, brings to Paris the experiences of 15 artists united by a sense of being pushed and pulled between places, people and events.

The Palais de Tokyo, Paris’s primary showcase for emerging contemporary artists, has in recent years been responsible for some staggeringly bad exhibition programming. More often than not, the venue has proposed a curatorial agenda informed by a desperation to keep up with art world fashion and a paradoxical obsession with a curse common to many French art institutions: good taste. Generally speaking, good thematic ideas are diluted to the point of flatness, nullified by platitudinous sentiments, boring work and baffling presentation. As such, it would be reasonable to approach Dislocations, an exhibition made up of work by artists from the MENA countries (plus Afghanistan, Myanmar, Ukraine and France) with a sense of trepidation.

Yet against expectations, this small show is impressive. The premise is a simple one, free of extraneous intellectual conceit: all 15 participants are known for work that meditates on the theme of exile. Many of them – indeed, perhaps most – have themselves escaped political turmoil or conflict in their countries of origin. Painting, photography and textual pieces are well represented, while video (a medium Parisian curators usually don’t hesitate to privilege) is absent. If any one style dominates, it is textile art, from tapestries to conceptual pieces to – in one instance – wearable clothing. Colours are bright and the layout of the displays inviting, all of which begs the question: why can’t more shows be like this?

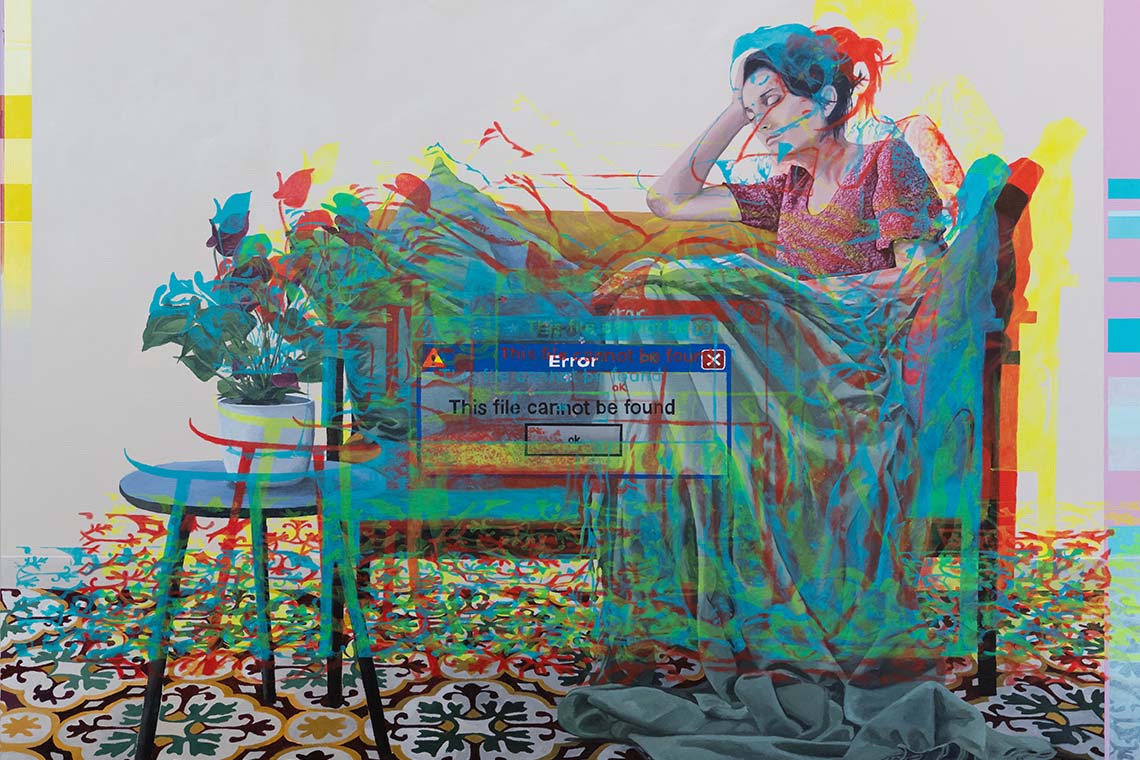

The first works encountered are a pair of paintings – Disparition, from her Human Error series (2022–23) – by Paris-based Palestinian artist May Murad, whose interests lie in the virtual world’s gradual encroachment into the real one. Hung on opposite sides of a dividing wall, both give us an identical composition: the artist herself slumps on a sofa like a 19th-century salonnière, her dress spilling out over the complex mosaic pattern of the tiled floor. To her left, flowers bloom in a vase perched atop a small coffee table. Into both works, however, Murad has introduced disruptive elements. In the first, her own likeness is left unpainted; at the centre of the image, a circular download graphic is accompanied by a caption informing us that loading is “75% complete”.

The second work from the series is altogether more haywire. The drawing’s lines are triplicated in aggressive digital colour, like a mediated representation of what it feels like to experience a bad acid trip. An error warning, complete with hazard signs, fills us in: “ERROR: THIS FILE CANNOT BE FOUND”. What Murad’s paintings, which share much in common with the ubiquitous school of zombie figuration, have to say about the condition of exile may not be obvious. But the artist, born in Gaza in 1984, makes a poignant statement here: when you can’t go back home, nothing can ever be quite right – however strongly Instagram might otherwise insist.

Image courtesy of the artist & galerie Marcelle Alix (Paris). Photography by Aurélien Mole

A similarly affecting contribution is the Afghan Rada Akbar’s Survivor and Advocate, from her Abarzanan–Superwomen series (2020) and one of several portraits she has made of female compatriots in the form of elaborate dresses. Hung over the kind of mannequin you might encounter at the workplace of a 1920s Parisian couturier, the dress itself is an Art Deco marvel, one half in black velvet, the other in rose-gold silk, from which extrudes an angel’s wing of drapery. It is, we learn, an homage to Shakila Zareen, a woman forcibly married off to a middle-aged man as a teenager and shot in the face when she tried to escape. Now permanently mutilated and living in Canada, she is an activist attempting to support women in similar situations. A ring of flames embroidered around the garment’s hem pays tribute to her courage and phoenix-like recovery.

Materials – often humble in their associations – are deployed to interesting effect. Myanmar’s Nge Lay, forced to leave her country in 2021, gives us a dirty mattress pockmarked with the encrustations of use and snaking lines of embroidery. A shabby sheet of gold lame heaving at its sides alludes to her homeland’s tourist board nickname, “the golden land”. The reliably brilliant Palestinian artist Majd Abdel Hamid provides a dozen or so delicate little tapestries that echo the abstract compositions of Josef Albers but turn out to be floor plans of the windowless safe rooms in which Beirut’s inhabitants (including the artist himself) took shelter during the disaster that befell the city in 2020.

Photojournalist Ali Arkady, meanwhile, has transferred his images taken in the course of the war without end raging in his native Iraq onto broken shards of concrete. Seeing them piled up in a gallery corner, like so much rubble, is undeniably powerful. Perhaps best of the lot here is Armineh Negahdari, who fields an anarchic menagerie of bizarre little figures. Vaguely based on ancient effigies discovered in tombs, they represent characters or stereotypes observed in the artist’s native Iran, each gesturing histrionically. Negahdari’s section, bolstered by a handful of his Twombly-like works on paper, is a delirious howl of absurdist expression.

There are low points, to be sure: I don’t know what justifies the presence of France’s Cathryn Boch, who has provided a cloyingly twee political tapestry fashioned from boat sails; nor did I think Syrian artist Sara Kontar’s text and photography installation Série Towards a Light was well-served by its presentation. But on the whole, standards are high and the artists worthy of close attention. Just perhaps, it’s time to give the Palais de Tokyo another chance.

Dislocations runs until 30 June 2024