The Mauritanian artist, feminist, activist and founder of ArtGallé speaks about the power of art to enact societal change and the role of the artist in being a voice for those who have none.

Canvas: How did you first discover your passion for art?

Amy Sow: I live in Nouakchott, Mauritania, and grew up in an artistic household. Art spoke to me from a young age. For me, it is a tool of communication, it’s my life, it’s everything that I do.

What led you to painting in particular?

My father used to give us drawing lessons, which pushed me to seek other media to express myself further. At first, it was not easy. Artists were difficult to find in Mauritania at the time, around 1999, so I worked alone before then discovering a group of like-minded people. Together we founded our first organisation, and it’s really there that I grew as an artist. I am completely self-taught; I never went to art school. I have been lucky enough to have artist residencies and exhibitions abroad, which have really encouraged me to use painting as a means of communication.

Are there any places in Mauritania where artists can train?

There are no art schools, which is why ArtGallé, the organisation I founded in 2017, encourages artists and young people, especially women, to come together to create art and also to recharge, because these spaces are missing in Mauritania. There are no galleries or permanent exhibition locations. Little by little, artists here are organising themselves to create more spaces to show their work. The Institut National des Arts (INA), an educational institution with the aim of promoting arts and culture across Mauritania, was created two years ago, in part due to our efforts. Things are starting to move forward and take shape compared with before. As artists, we are working hard to tell politicians that young people, young artists, need these spaces to share ideas, to develop themselves. There are no art programmes in schools, but some artists travel around teaching culture lessons and we have travelling workshops which go across the country to teach people about art.

What obstacles do aspiring artists face in Mauritania?

It’s easier for men than for women, but even then people will always try to convince you not to be an artist. They think it’s better to work in a desk job, when in reality being an artist is a proper career. However, people are understanding more that artists are crucial to the development of a place. A country without artists cannot evolve. We are thinkers, so in order to try and filter out these thoughts, governments try to sideline us. We as artists dare to speak, to say things as they are, and the authorities don’t want that.

Where do you find your inspiration?

From everyday life. We all know that the world is quite troubled, and Mauritania is one of those countries where rape and violence are very common. I started to think about exploring these subjects in my art, which is when I realised that I could transmit messages through my work and give voice to these issues. It’s taboo to speak about these topics in our society, but through art I can condemn this violence against women. I myself am a victim of it, so there is no one better placed than me to talk about it. I speak out as a refusal to be silent, almost as a sacrifice, because if no one says anything for fear of shame or upsetting the status quo, things will continue for centuries without changing.

What is the reaction in Mauritania to your art? Have you seen any tangible changes in society?

There is a lot more interest, especially on the part of young women, in the arts. Women are starting to become more aware of the issues they are facing, with more interest in the question of rights and justice. Sometimes, when you suffer so much, you begin to normalise your situation, even when it shouldn’t be the case. It’s not normal to suffer this violence, so it’s important to report it, to talk to loved ones about it. I’ve noticed a big shift in that, perhaps because there are a few Amy Sow types out there who dare to say something, which gives others the confidence to speak up as well. Of course, there are other female activists fighting for the same things, whereas for me it is really through art, which is rare here.

How do you depict the subject of violence against women and the question of rights in your work?

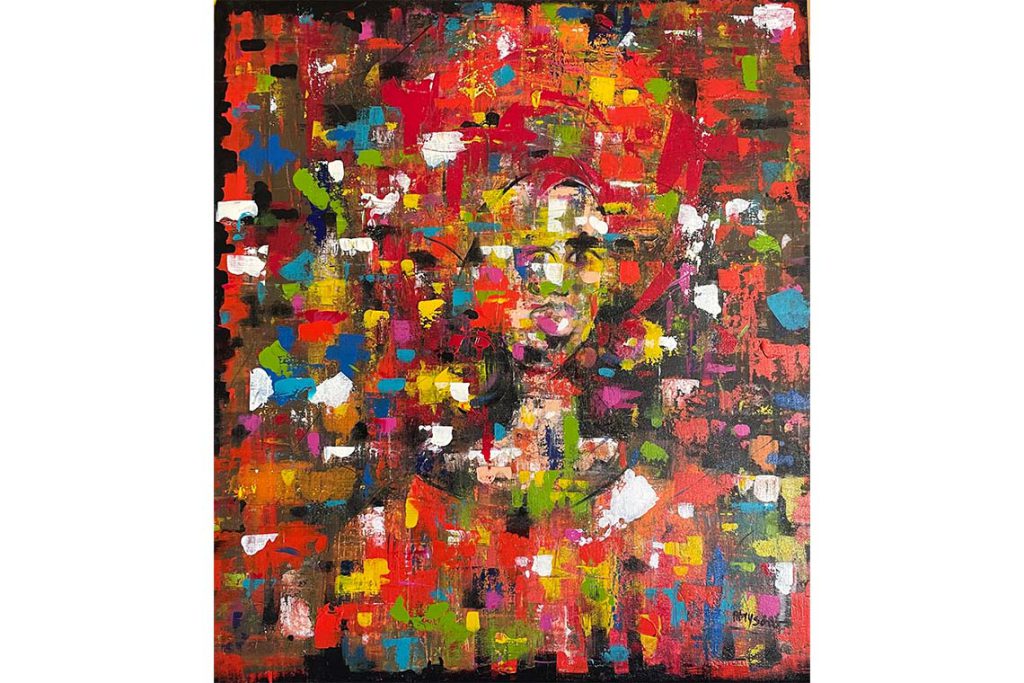

My paintings feature the identity I have created for myself, this strong woman who dares to reveal herself, to denounce things, and to speak up through this character. It’s always me, with my scarf around my head, leaving my mark, to say that I will fight. My photography deals a lot with the difficulties linked to water access in Mauritania, which women suffer from too. Also, I do installations and performances. My latest one at ArtGallé spoke about the suffering of women while dyeing clothes. Women used to have a sort of stick they would hit the fabric with after dyeing it. They would beat it for hours, and even just hearing that sound provoked something in me. It was as if they were releasing something through the hitting, their anger, their suffering.

Your exhibition in 2022 in Luxembourg spoke about issues linked to Covid-19.

I had two paintings in the show organised by Barthélémy Toguo, a Cameroonian painter and visual artist, which I made during the pandemic. During the health crisis, a lot of things came to the surface. Being home all day forced both men and women to reveal facets of themselves which were hidden previously, due to the separation of work and home. Suddenly we were laid bare. The faces in the paintings are somewhat covered, as a metaphor for this hidden face of people.

Are there many exchanges between Mauritanian artists and their colleagues abroad?

Yes, we feel connected to other artistic communities. For the latest ArtGallé festival, which takes place annually and is a meeting of local and international artists, we invited representatives from France, Senegal, Togo and Tunisia. I have had residencies outside of Mauritania, in Tunisia, Morocco, Senegal, France, Spain and Italy, and a lot in the Maghreb.

How do you see the future of the artistic scene in Mauritania?

I see a new dynamism, and some change. We are not giving up, and with the little means we have we must continue. I think it will work. Other organisations like ArtGallé are now starting to form, so between us, we will manage.

What about the future of your own practice?

I have a travelling caravan project, Caravane l’Art de Lutter Contre les Violences aux Femmes et aux Enfants (Art Project to Fight Against Violence Against Women and Children). The idea is to go around Mauritania and raise awareness about women’s rights, to encourage women’s independence and girls’ education and to stop genital mutilation. The goal is to finish each caravan with an artistic activity, which engages the local community and allows them to process the ideas we have explored. Plus of course I am continuing to work on the ArtGallé festival and other artistic projects.

This interview first appeared in Canvas 117: The Maghreb Issue