Présences Arabes – Modern Art and Decolonisation, Paris 1908–1988 at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris chronicles the participation of Arab artists from former European colonies in the Paris art scene while showcasing the impact of decolonisation on Parisian art of the 20th century.

The exhibition currently showing at the Musée d’Art Moderne in Paris, Présences Arabes – Modern Art and Decolonisation, Paris 1908–1988, is the result of four years of research by curator Morad Montazami, with Madeleine de Colnet and Odile Burluraux. The exhibition goes beyond the misunderstanding of a French national art history, explains Montazami. It depicts works by artists who have strong links to France and who also happen to be of Arab origin and also reflects on the role that the French capital has played in their artistic emancipation and in new ways of decolonised thinking. “The exhibition is intended to show national [French] audiences that Arab art has always existed here,” the curator tells Canvas, as if stating the obvious, surrounded by works of Arab art from so many French collections, including the Bibliothèque Nationale and the Centre Pompidou. The show unpicks the complex interplay of French and Arab themes and media – it is interesting to see the work of established Arab artists such as Etel Adnan, Baya and Inji Efflatoun dating back to their student years in Paris and to be able to see images of artists such as Effat Naghi in the presence of André Lhote and his wife, or in the artist’s studio near Montparnasse in Paris. Such a broad array of Arab artists’ work is situated in surprising coexistence in the capital, giving Paris added international – and particularly Arab – significance.

In terms of layout, Présences Arabes follows four chapters or chronological themes, beginning with Nahda: Between Arab Cultural Renaissance and Western Influence, 1908-1937. An-Nahda is ‘the Awakening’ of European politics and culture to the Arab world, and exemplified in a c.1908-10 oil painting by the Lebanese philosopher Khalil Gibran and which depicts his friend, the freelance journalist and suffragette, Charlotte Teller. Gibran attended the Académie Julian, an art school and studio founded by the artist Rodolphe Julian in 1868 and frequented by artists such as Dubuffet, Derain, Duchamp, Léger and Matisse. Later, at the École des Beaux-Arts, Gibran became interested in symbolism, painting spectral visages of an older and younger woman alongside Teller’s face. Not only does this give viewers an insight into the artist’s future philosophical leanings but it also reflects on the importance of Teller’s beliefs in women’s liberation and in its subsistence.

Photography © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Philippe Migeat

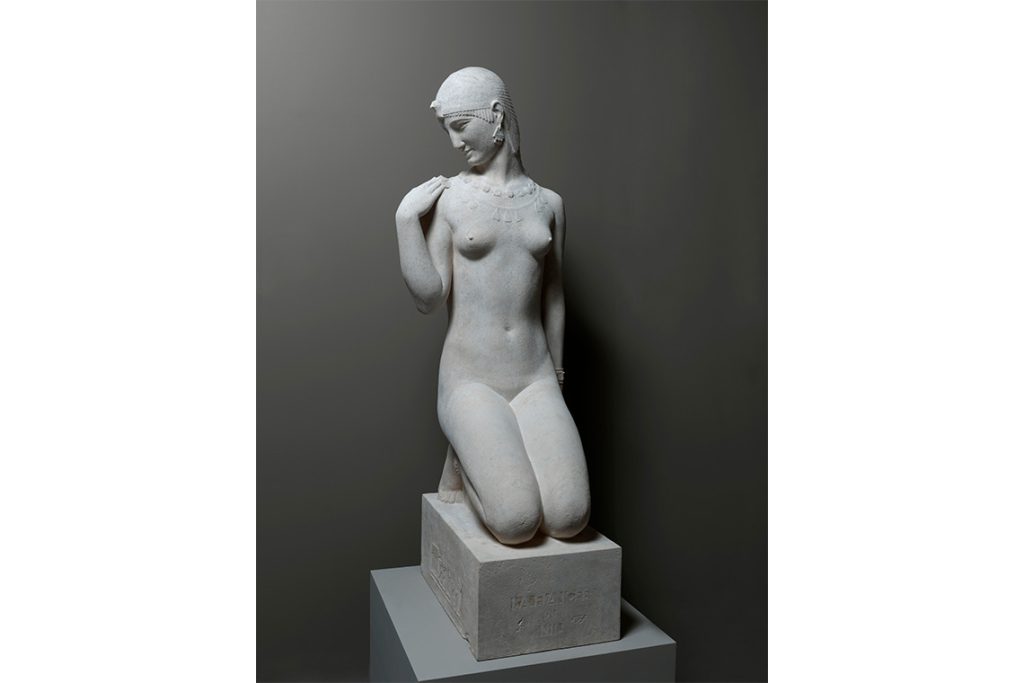

Also in the first gallery is the delicately detailed sculpture Arous el-Nil (‘Fiancée of the Nile’), c.1929 by Egyptian artist Mahmoud Mokhtar. A graduate of L’École des Beaux Arts in Paris, Mokhtar portrays a kneeling female figure carved in white stone, with a serpent band around her head and a pectoral necklace, also borrowed from ancient Egyptian iconography. Her delicate features and short haircut are in the unmistakable flapper style of the 1920s, with the Egyptian references showing Mokhtar’s pride in his desire to modernise perceptions of Egypt after its 1922 independence.

The independence of French and British colonies bordering the Mediterranean and in the Levant, such as Lebanon and Syria, Egypt and Jordan, brought an air of lightness and liberation. The exhibition explains how artists from these regions and from Iraq became involved in abstract, expressionist and surrealist movements in Europe, particularly in Paris. The second chapter in the exhibition, Goodbye to Orientalism: the Avant-garde Counter-attack, 1937-1956 includes work by Georges Koskas, Salah Yousry, Samir Rafi, Inji Efflatoun and Saloua Raouda Choucair. These artists express the mixed feelings and complex reality of their changing lives, and of the new societies being formed in their own countries.

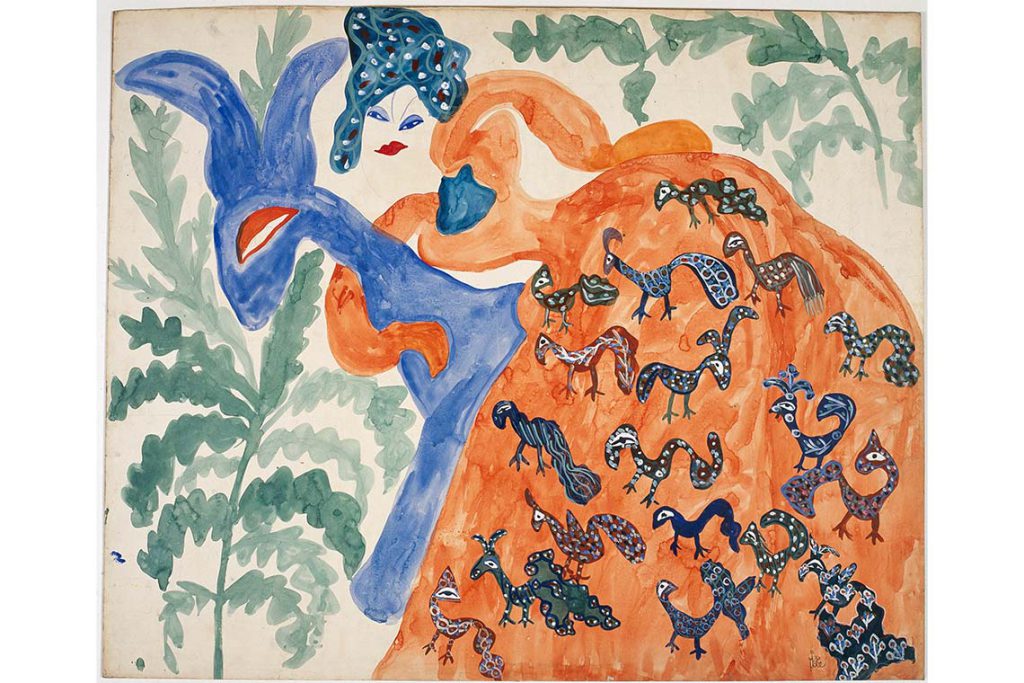

Studios of artists such as Fernand Léger, André Breton and André Lhote were inspiring for Arab artists. Iraqi artist Jamil Hamoudi’s 1951 Abstract Composition under the name of ‘Dorival’, from the Centre for Industrial Creation at the Centre Pompidou, shows Hamoudi’s gradual development of abstraction to the animation of calligraphic script and the Hurufiyya style, a movement that bridged traditional calligraphic script and contemporary art. Hamoudi’s painting is signed in Arabic, but other artists used Latin script or signed under alter egos that were easier to pronounce, such as “Baya” (the Algerian artist Fatma Haddad-Mahieddine), also in the exhibition. Her Femme en robe orange et cheval bleu (Woman in an orange dress and blue horse) c.1947 depicts a leaning figure with an elaborate head-dress and expressive lips and almond-shaped eyes that echo the colourful fauvist and surrealist paintings of the past.

© Othmane Mahieddine

Similarly, Saloua Raouda Choucair’s Paris-Beyrouth (1948) is a colourful and abstract landscape of shapes that recall the populist, cubist compositions of Fernand Léger. Choucair, however, uses shapes that relate specifically to Arab iconography, including a star found very often in Islamic tilework, a lighthouse shape that recalls Alexandria’s iconic Pharos lighthouse, a wonder of the ancient world. In the centre of the painting stands a tall pointed blue column, representing an ancient Egyptian obelisk which once stood at the entrance to the temple of Ramses II in Luxor. It was gifted as a diplomatic gift to France and now stands in the Place de la Concorde in Paris.

Décolonisations: Modern Art Between Local and Global explores the second wave of independence, that of the French colonies of Morocco and Tunisia in the 1950s, as well as the French government’s bitter war with Algeria during 1954–62, which tainted the country’s politics and culture during this period. Paintings from artists of the Casablanca Art School, such as Farid Belkahia and Mohammed Melehi, remember local Amazigh traditions and crafts in their subject matter, materials and styles. The Casablanca Art School was the title of Montazami’s successful exhibition last year at Tate St Ives, and recently [LL11] at the Sharjah Art Foundation.

In many ways, modern art was used as a diplomatic tool by the French government, since it was keen to maintain ties with its previous colonies of Lebanon, Morocco and Tunisia. As the war in Algeria raged, artists such as Shafic Abboud and Ahmed Cherkaoui became involved in exhibitions such as the Biennale de Paris and the Biennale des jeunes artistes de Paris. For generations of artists from the Maghreb, Paris was their gateway to the world.

Finally, Art in Struggle: From the Palestinian cause to the “Arab Apocalypse”, 1967-1988, tells recent stories of global political crises. The Arab Apocalypse (1980) by Etel Adnan, who studied philosophy at the Sorbonne in 1949, is a collection of unfolding artist books which the artist wrote in Beirut during the siege and subsequent massacre of Tel al-Zaatar, an area which was primarily home to Palestinian refugees. expressed her growing concerns about the situations in Lebanon and Palestine. Through films and media, the exhibition only touches upon political events themselves. Instead it focuses on the movement and development of art and on the perceptions of artists working in Paris during that time.

The effect is a little surreal. While some artists are haunted by their personal past, such as the Iraqi artist and surgeon Ala Bashir – his Untitled of 1982 shows a skinless body with hands pulling at it from the inside – others use art as a way of recording events and their feelings. In his 1986 work Les Refugiés (The Refugees), from the collection of the Institut du Monde Arabe, the Syrian artist Fateh Moudarres evokes an air of devastation and loss in his depiction of mixed crowds of faceless people, fleeing with their animals on foot.

“Can we affirm that Paris was an Arab capital? From the point of view of artistic trajectories, nothing prevents it,” asks Montazami suggestively in his accompanying essay. Présences Arabeis an important exhibition that recalls the creative influence of countries such as France and their importance as melting pots of creativity and change. The show is also taking place at a time when political tensions in France and in the Arab world are running high – this intense and extremely well-structured exhibition is a powerful reminder of the creativity of Arab artists in the face of resistance and change.