Through the creation of an urban environment in embroidered rugs, Alia Farid documents the vestiges of Arabic migrations to Latin America and reveals connections between the two regions that had been hiding in plain sight.

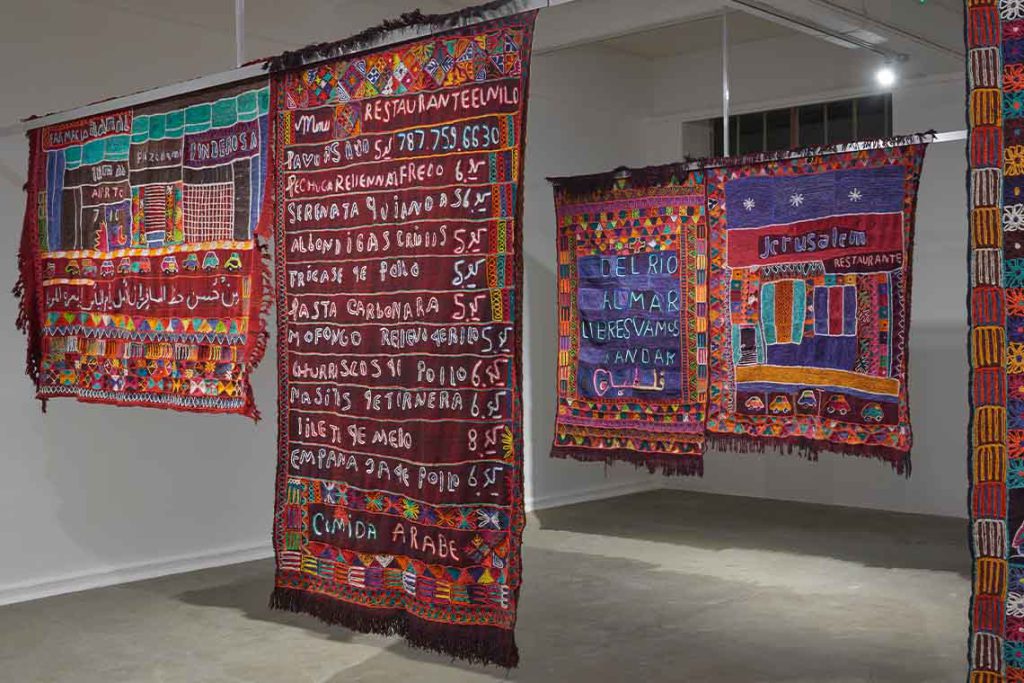

Great swathes of colour welcome visitors to London’s Chisenhale Gallery, as long rows of tapestry-like rugs arrayed down the full length of the gallery create a vibrant scenography. Their imagery combines architectural facades with Spanish and Arabic text, stylised birds, flowers, clouds, lines of cars and what look to be advertising boards outside shop fronts, bordered by dense decorative motifs. One piece resembles a menu, with prices listed down its side.

This woven panorama comprises Elsewhere, the first UK solo exhibition of artist Alia Farid and a major commission by Chisenhale Gallery. Taking in the full breadth of the presentation requires walking up and down the rows, whereby an urban environment begins to take shape. Each rug is crammed with overlapping symbols and cultural references which, we learn, illustrate the Palestinian diaspora community in Puerto Rico.

The exhibition text terms Elsewhere “a growing material archive”, part of a larger research project mapping Arab and South Asian migration to Latin America and the Caribbean. Indeed, this exhibition presents only the first chapter of the project, built on more than a decade of research. Its current display is the result of Farid working closely for two years with traditionally skilled weavers in Samawa, southern Iraq, who condensed her extensive multi-format research into these fabric forms. She refers to them, aptly, as documents and maps, such is the way that individual threads contain so much information.

Farid is building serious momentum in her rise through the art world. Following institutional solo shows at Kunsthalle Basel, Contemporary Art Museum St Louis, and MCA Chicago (all 2022), and with her installation Palm Orchard (2022) taking a central position at last Whitney Biennial, she has arrived in the UK having made quite the splash. Her ascendancy has been recognised in winning the Lise Wilhelmsen Art Award, awarded by Norway’s Henie Onstad Kunstsenter and involving a major show in Oslo later this year, and her installation In Lieu Of What Is (2022) is currently exhibiting in Cardiff and nominated for the Artes Mundi 10 prize.

It is remarkable that at each of these key career landmarks Farid has been working in a different discipline, covering installation, sculpture, photography and film. Elsewhere now adds textiles and embroidery to the ever-expanding list. In a curatorial interview conducted with Chisenhale, Farid explains that as landscapes are not part of the Arabic painting tradition, she became interested in tapestries and textiles as a means of expressing cityscapes through recognisable architectural motifs.

Born in Kuwait and raised between there and Puerto Rico, the artist grew up intuitively straddling the two supposedly disparate countries. It was not long, however, before she discovered the extent of the Arabic community in Puerto Rico, a migratory phenomenon that she has since investigated thoroughly and which has formed the conceptual bedrock of Elsewhere.

Palestinian migrations to Central America began towards the end of the 19th century, when economic prospects in the West began to far outweigh those in the collapsing Ottoman empire and the Ottoman army’s conscription policies drove more young men away from the region in the lead up to the First World War. These early mass movements were dwarfed however by the events of the 1948 Nakba and 1967 Palestinian exodus, when over 700,000 and 325,000 refugees respectively were forced to leave Palestinian territories due to Israel’s land-grabbing wars. Palestinian refugee movements into Egypt, Jordan and other neighbouring territories have been more closely understood than the much longer journeys that headed West, taken by many thousands of emigrant communities to countries such as Honduras, El Salvador, Puerto Rico and other Caribbean islands.

The motivations and nuances behind these migrations, some voluntary, some not, are narratives that have long been overlooked by Western commentators, and Farid began to correct this with the research grant she was given in 2012 to study the architectural provenance of five mosques across Puerto Rico. “These were markedly different from the arabesque architecture that accompanied Spanish colonialism,” she continues in the curatorial interview, “They were contemporary, vernacular and community initiated.”

As now depicted in the rugs, these mosques act as conceptual touchstones to understand the reality of the architectural migrations that Farid is tracking. Their quirks and specificities have been lifted straight from the nostalgic memories of displaced populations yearning for their homeland. Architecture and language have become the structural pillars of Farid’s research, with both assuming central roles in the visual semantics of the show. Text functions in the same concrete way as the buildings, signifiers of culturally specific references. The restaurant menu listing ‘COMIDA ARABE’ (Arabic Food) immediately illustrates the parallelisms of the twin cultures and demonstrates how matter-of-factly Palestinian influence has permeated the day-to-day Puerto Rican landscape.

In Farid’s words, “translation is impossible”, and this is emphasised in the clear methodology of the show. Elsewhere’s great strength is that it doesn’t get caught up in attempts to conflate Palestinian and Puerto Rican experiences, bundling them together under overarching narratives of shared colonisation, oppression and exploitation, but rather is able to hold the two communities distinct and therefore more clearly understood.

From her bi-cultural vantage point Farid has done incredible work to piece together narratives fragmented by events half way across the world, and trace back ripples of cause and effect to their point of origin. Out of sight out of mind is a sad truism, whereby the far-reaching consequences of colonial oppression are often diluted in the act of migration, lost in the time and distance spent moving away from trauma. Farid counters this by revealing the contemporary results of a diaspora community that has been sitting in plain sight for so long. Thanks to the incredible depth of her research, combined with her lived experience between the two cultures, her eye for detail is well honed, perhaps making her one of the few people worldwide who could reveal with such clarity the alternative cities living within modern-day Puerto Rico.

Suddenly, having explored the details of the tapestries for so long, it registers that these urban environments, buzzing with atmosphere, are empty of people. There are no figures in any of them. Even though people are intrinsically at the heart of any migration, here Farid removes them from focus and instead leaves the vestiges of their presence: pharmacies, mosques, shops, roads. Walking among the hanging rugs, arranged in such a way as to leave passageways between what come to resemble blocks of buildings, the gallery visitors become the population of this alternative city. Elsewhere is a living archive, a singularly vibrant anthropological record, and once activated by its own audience, transports them far, far away.