In Daughter B.W.A.S.M. at Pilar Corrias in London, Tala Madani pairs her character Shit Mom with AI-generated robot daughters to interrogate the longstanding equation of women with machines

Tala Madani’s Shit Mom is having an existential crisis. In A.I. (W.C. Crisis) (2025), the artist’s scatological anti-heroine is faced with a toilet that has become animate, its cistern transformed into a moon-like face threatening to flush her into oblivion. It is a darkly comic moment in Daughter B.W.A.S.M., an exhibition that uses faecal humour – and at times, faecal despair – as a vehicle for serious cultural critique. It traces a lineage from the experiments of early modernism to our current moment of AI saturation, examining how women’s bodies have been consistently reduced to mechanical functions along the way.

Daughter B.W.A.S.M. – the acronym standing for ‘Daughter Born Without a Shit Mom’ – takes as its departure point Francis Picabia’s 1916 Dadaist painting Fille née sans mère (Daughter Born Without a Mother), which appropriated a diagram of a steam engine, overlaying it with gold and green to satirise the mechanisation of life and the classification of machines as female. Madani brings Picabia’s two-dimensional mechanomorphic vision into our three-dimensional present, where AI has replaced steam engines as the dominant technology shaping daily existence. At Pilar Corrias, she constructs a wooden installation that mirrors Picabia’s work, predictably desecrated with smears of acrylic-painted excrement – a visual manifesto declaring that the idealisation of the mechanical, the perfect and the pristine remains fundamentally at odds with the messy realities of embodied existence.

The exhibition’s central tension is immediately legible: AI represents perfection, precision and the idealised; Shit Mom embodies its impossibility. First appearing in Madani’s work around 2019 – significantly, not long after the birth of her first child – Shit Mom is the antithesis of idealised motherhood, a shape-shifting faecal figure who stands in opposition to every sanitised fantasy about maternal experience. In earlier work, the character served primarily to articulate maternal ambivalence and anxiety; here, Madani expands Shit Mom’s remit to encompass a broader feminist critique of how technology perpetuates time-honoured patterns of reducing women to reproductive functions and domestic labour.

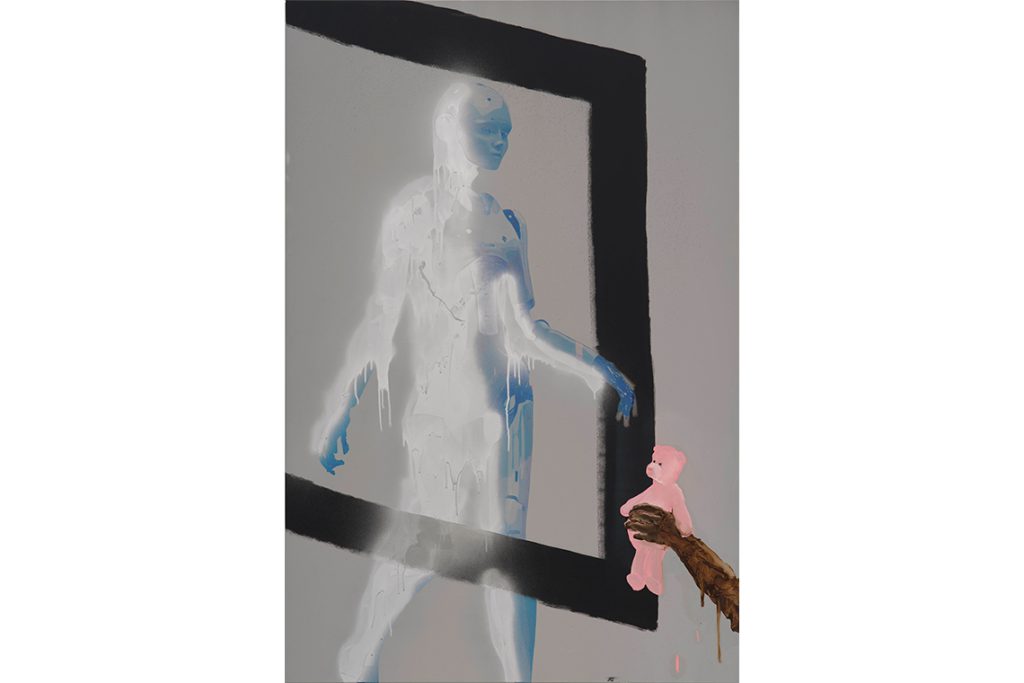

The paintings are striking in their technical approach: Madani begins with screen prints of AI-generated robot figures, their forms rendered with the algorithmic precision characteristic of machine learning, then works over them with gestural strokes of oil paint in varying shades of brown. The result is a collision of aesthetics – the sleek, polished surfaces of sci-fi androids interrupted by organic, hand-painted marks that read alternately as shadow, decay and excrement. This juxtaposition gives the work its unsettling power, the way in which digital perfection and bodily messiness exist in uncomfortable proximity on the same canvas.

In D.B.W.A.S.M. (Pink Teddy) (2025), Shit Mom proffers a vivid pink teddy bear to an ethereal, fading robot daughter. The teddy – which also appears in yellow in D.B.W.A.S.M. (Teddy) – remains solid and saturated whilst the bot figure dissolves into transparency. It is a pointed juxtaposition: the stuffed toy represents material reality, the tangible world of objects and comfort, whilst the AI daughter exists in a state of perpetual ephemerality. Shit Mom is not just providing a traditional token of childhood comfort; she is also offering a piece of the real world itself, something that will not disappear when you refresh the screen.

This gesture of maternal care through contamination recurs throughout the exhibition. In D.B.W.A.S.M. (Head Swap) (2025), Shit Mom replaces the heads of two AI bots with heads made of excrement. In D.B.W.A.S.M. (Patchwork) (2025), she patches pieces of her own faecal body onto the bots – literally giving of herself to save them, to make them real. Most viscerally, in D.B.W.A.S.M. (Umbilical Discord) (2025), she nourishes a bot with an umbilical cord made of shit. These are acts of love rendered in the most deliberately repellent visual language possible, forcing viewers to confront the fundamental incompatibility between the pursuit of technological perfection and the biological, messy, imperfect reality of human care and connection.

The exhibition’s two video works expand this critique into the realm of art-historical citation and motion itself. S.M. Ascends (2025) shows Shit Mom caught in an endless Sisyphean ascent of staircases – a clear nod to Marcel Duchamp’s 1912 painting, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2, although here the nude is ascending rather than descending, and doing so through an infinite procession of found staircase images. Some staircases are in near-empty houses, others feature Persian rugs, while still others reveal ultra-modern interiors or cupboards tucked beneath the stairs. Everywhere she goes, Shit Mom smears the walls with excrement, marking each domestic space with her presence. To descend, she slides down the banisters, landing in a messy heap.

The video’s installation in a bright white room dedicated solely to the screen accentuates Shit Mom’s transgressive nature, her brown smears appearing all the more confrontational against pristine walls. It is a potent metaphor for both the endless, repetitive labour of motherhood and the metaphorical ascension promised by technological progress – an ascension that, Madani suggests, may be as futile as it is exhausting. The video finds visual echo in Shit Mom on Rail (Partition Play) (2025), an oil painting which captures what might be the character’s only moment of pure joy – legs akimbo, arms raised, whizzing down a bannister with apparent abandon.

Shitmom Learning How to Walk (2025) inserts Madani’s protagonist into sequences from Eadweard Muybridge’s pioneering motion studies, which famously depicted women actors walking, carrying objects and dancing. Shit Mom attempts to mimic the women’s gestures, learning from their poses, but repeatedly falters and collapses into a formless heap, leaving trails of excrement in her wake. It is a poignant commentary on the impossible standards women are expected to meet – standards established through centuries of visual culture that have objectified, studied and attempted to perfect female movement and behaviour. Even Shit Mom, who exists precisely to reject such ideals, cannot help but try to measure up.

The domestic interior – represented by those endless staircases and varied architectural spaces – becomes a space of perpetual labour rather than sanctuary, where ideals are simultaneously enforced and transgressed. Shit Mom’s journey through these spaces literalises the ways motherhood marks and transforms domestic environments, whilst her encounters with AI daughters illuminate how gender roles are not just enforced but encoded into the very technologies that increasingly populate our homes. The exhibition asks us to consider what happens when the private – the messy, embarrassing, biological realities of care work and motherhood – refuses to remain suppressed, smearing itself across every surface that demands perfection.

Throughout her career, Madani has deployed vulgarity as a tool for dismantling cultural pieties. Daughter B.W.A.S.M. extends this approach, using bodily abjection to interrogate the gendering of technology. In an era when AI assistants are given female names and voices, when domestic robots are designed with curves and programmed with nurturing personas, Madani’s Shit Mom serves as a necessary corrective – a reminder that the mechanisation of care and reproduction is not progress but a continuation of long-standing patterns of gendered objectification. The work succeeds precisely because it refuses to be tasteful, trading in a deliberate crudeness that matches the bluntness of its critique.