The artist duo discuss the multiplicity and nuance of their practice, which moves between media – from video and sound to installation – to imagine alternative futures for Palestine.

Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme started working together after a chance meeting in London, where they were both studying. “It was about 15 years ago,” Abbas recalls from their home and studio in New York. “I was at Middlesex University and Ruanne was at Goldsmiths College. We had known each other before, but we didn’t know that we were both in London.”

Abou-Rahme was working with video and images, and Abbas with sound and music. They were frustrated by the limitations of one medium: “We couldn’t express the breadth of our ideas, or our social and political thinking”. Collaborating offered an opportunity to open up their practice, and to express themselves through multiple approaches. It was also a way of doing things differently, of “moving away from the ego of the artist”.

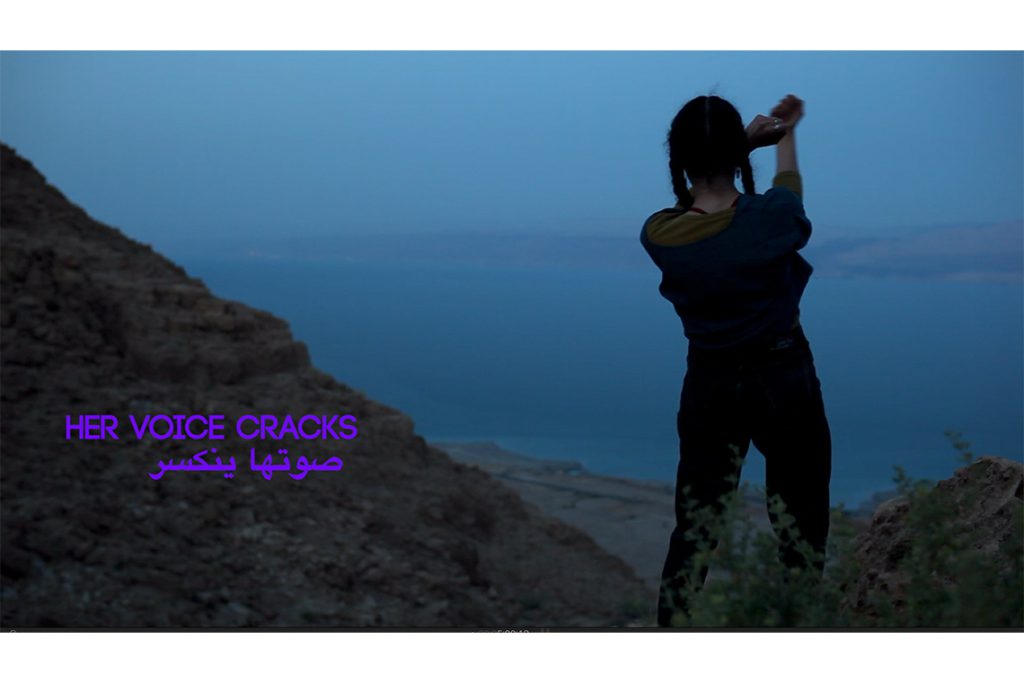

Abou-Rahme describes their practice as “adisciplinary”, their work moving between and containing multiple media, and being expressed through various forms: “We actively refuse the idea of having a discipline, and what the market imposes”. And Yet My Mask is Powerful (2016–18), for example, extends across two parts, and various versions. Part One is a five-channel video projection, with two-channel sound, alongside an installation of tools, bricks and boards. The project references journeys taken by young Palestinians “to the sites of their destroyed villages inside Israel, as an avatar for rethinking the site of the wreckage… [where] in these returns, the site of thewreckage becomes the material from which to trace the faint contours of another possible time”. The site is “reactivated” through singing, eating and dancing, while it lives on through the soil, wild thorns and pomegranate trees. In Part Two, hacked 3D-printed versions of Neolithic masks – taken from the West Bank and stored in private collections – are placed in an installation displayed on tables and cork boards, with documents, tools, books, cardboard boxes, dried plants, pine branches, house remains, broken ceramics, garbage and mini projections, “confront[ing] the apocalyptic imaginary and violence that dominates our contemporary moment”. The work intersects “between performance and ritual, body and artefact, thingness and virtuality”, splicing together a counter-narrative to the dominant tale of the present, and layering forms to activate numerous “returns, flash-forwards and moments of déjà vu”.

Video still. Four-channel video projection (HD, colour, sound) on partition wall, metal and concrete panels, photographic gel. 34 minutes, 34

seconds. Performers: Rima Baransi, Haykal, Julmud, Makimakkuk. Co-commissioned by The Museum of Modern Art, New York and Dia Art

Foundation, New York. Image courtesy of the artists

The idea of returns, repetition and echoes appears (and reappears) throughout the practice of Basel and Ruanne (the name under which the duo prefer to be known), both in terms of the problems of repetition – “how images from Palestine lose their potency through repetition, and become mundane” – and its potential in relation to returning to something – “The idea of return is a big issue for Palestinians”. Through the use of archival material, looping sound and video, and creating multiples through publishing, Basel and Ruanne challenge the linearity of time, and the idea that things occur in isolation. For them it is a way of fighting against the capture of time by colonial, capitalist systems of power, “[which] suffocates our ability to imagine different possibilities, different ways of being in the world,” says Abou-Rahme.

For Basel and Ruanne, one way of becoming “unbound” is in thinking about the potential of echoes: “thinking about how through improvised song, voices are moving between spaces and, each time they are sung, there is a new improvisation that includes a different story”. A song can be sung in Iran, move through Syria and into Palestine, “changing through that process, but holding the inscriptions and echoes of what was before”. Even when an individual is singing, these improvised songs call out to a wider collective, and contain the voices and contributions of a choir.

In Basel and Ruanne’s work, material is collected and connected, so that fragments can be understood in the context of a long history. “This [capitalist, colonial] system tries to isolate events, rather than [show] something that is systemic, and systematic,” says Abou-Rahme. “So that the Palestinian question is just a singular question, not connected to other questions of dispossession and injustice. It becomes very important to refuse that, and to make connections.”

Fragments or parts – archival material, objects, performances and audio-visual material – gather together like puzzle pieces, undermining extractive practices. “There is a purposefully amnesiac quality of racial capitalism, it is constantly cannibalising everything, including time – everything just disappears,” Abou-Rahme continues. “It is constantly trying to put people in this situation of suspension, because it stops mobilisation.”

Image courtesy of the artists

One way that they resist the amnesiac quality of our time is through their process, which is rooted in long-term research. A large part of their work is conversation, reading, thinking and figuring out how to communicate their research, and how to reach the broadest audience: “Whether it is artefacts or knowledge, [this material] has been looted, it is being gatekept and we try to think of ways to circumvent that,” says Abbas.

Digital spaces, publishing and distribution are integral to their practice, as methods for widening access to their work and research, as the majority of their exhibitions are in Western Europe and America. For Basel and Ruanne, it is important that their ideas and work can travel, “shift and mutate, be unbound”, from the West, and from the art world. “For artists from the South, online becomes significant, publishing becomes significant and performance becomes significant,” says Abou-Rahme.

Performance art is “impermanent”, and does not need the same structural support: “It can be flexible, malleable and light”. While Basel and Ruanne’s work is conceptual, political and philosophical, they “operate in the field of affect… and embodiment”: “We are concerned with people being able to come in and feel something, which prompts them to think differently,” says Abou-Rahme. “There is an immediacy to performance, a vitality.”

May amnesia never kiss us on the mouth: only sounds that tremble through us (2020–ongoing) is a multi-part project rooted in communal song and dance, which examines how communities bear witness to experiences of violence, loss, displacement and forced migration. The project features archival recordings of people signing and dancing in communal spaces in Iraq, Palestine, Syria and Yemen, which Basel and Ruanne have been collecting for over a decade. Shown alongside recordings of new performances in Ramallah, created by the artists with dancer Rima Baransi and electronic musicians Haykal, Julmud and Makimakkuk, presented as live activations and a digital platform, the work conveys how through song and dance people can lay claim to space, self and collectivity. “We have been thinking about the body and the voice as important sites through which people are resisting erasure” says Abou-Rahme, “generating different possibilities for being, and imagining the world.”

Installation view of We know what it is for we who have used it at A Tale of A Tub, Rotterdam, 2018. Image courtesy of the artists

The digital platform is an indexed archive of Basel and Ruanne’s found video footage, presented alongside the recorded performances, which were originally meant to be presented live alongside video and sculpture works at MoMA. The shift in context, and scale, could flummox an artist, but for Basel and Ruanne it allowed them to embrace a broader audience, contain jumps in time and place both in the work itself and in the experience of interacting with it, and bring together a layered harmony of voices, movement and experience.

In their installations, Basel and Ruanne disrupt the distance between the audience and the space, placing them in the work, within a live or lived rhythm, whether that is performance, video, sound works or archival material. “It brings people into things they don’t necessarily want to be in,” says Abbas, catching people off guard by pairing “the affective” with conceptually challenging ideas.

Their work contains joy – “but not everyone is meant to feel it” –and disruption: “You are not able to completely hold onto it,” says Abou-Rahme. For Basel and Ruanne, bridging the gap between the work and the audience can encourage people to understand ideas and experiences that they didn’t before: “And that is the process of radicalisation, right?”

This profile first appeared in Canvas 110: It’s Electrifying