Confronting the different dimensions of history and truth, the artist seeks to find a path through to a real identity.

Born in the year of the Iranian Revolution, painter, installation artist, writer and curator Behrang Samadzadegan is a victim of the “inevitable burden”, according to writer Yasmin Moshari, that the people of Iran are faced with from birth: becoming absorbed by their country’s socio-political history. For Samadzadegan, the struggle is a never-ending and futile attempt to reconcile the past and the present and address the loss that inevitably results from the distance between them.

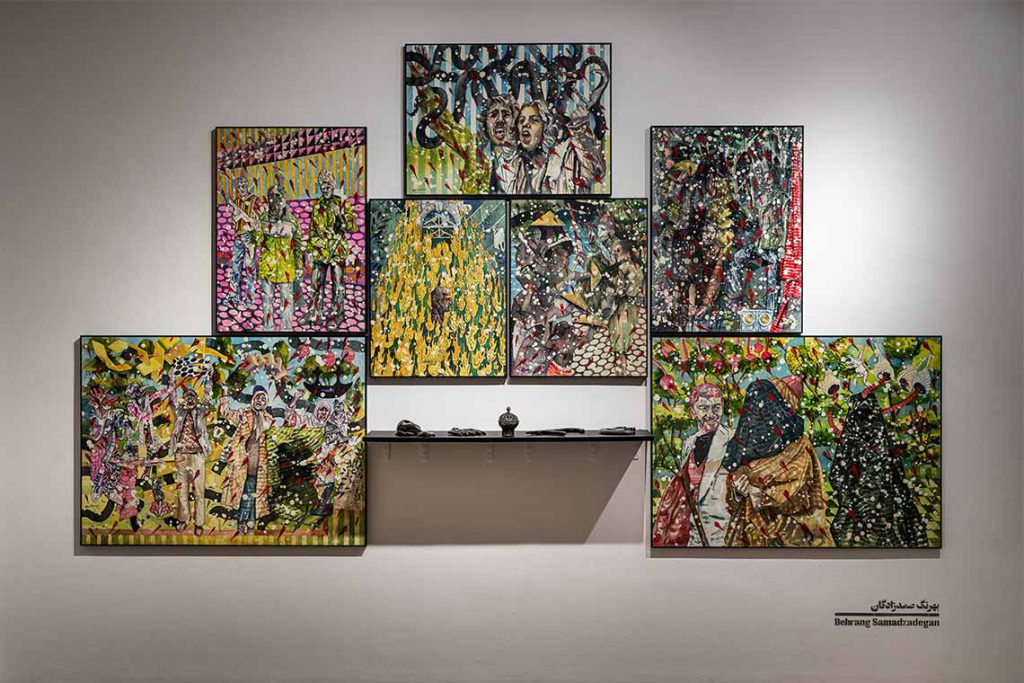

Samadzadegan’s painting practice grew out of a moment of realisation while looking at historical photos of the 1979 revolution. “I started talking to myself and saying, ‘I am living in the result and consequences of these vast events that I had no role in,’ and I tried to imagine what the truth of these photographs was, what was actually happening there.” His acrylic and oil paintings and installations in the first part of the 2000s looked at cultural and social identity in Iran, in bold criticism of cultural attitudes toward politics, religion, sexuality, education and art. Images of contemporary popular culture were merged with press images depicting terrorism and violence. In work ranging from abstract arrangements of stuffed toys to 2-D work drawing from literature, found photographs and advertisements, he sought to reveal the ways in which his country’s colonial history, civil rights movement and totalitarian politics inform understandings of Iranian society.

In the mid-2000s, Samadzadegan’s interest in the phenomenology of the image and how truth is represented became more central to his practice. Until then, his paintings often restaged ritual or historical narratives, but now they were presenting something entirely new, in fantasies or fever dreams that cannibalise images and elements from the 1979 revolution and add them to those of Persian classicism and Western art history and literature. They began a decade-long body of work he calls Heading Utopia, whose paintings, like dreams, never reach a resolution or present a conclusion, and like so many fantasies, live between fiction and truth, history and experience.

The idea of living between two very different times, before and after the revolution, without having had the opportunity to know both and bear witness to the shift, is a crucial component of Samadzadegan’s work. As a member of the first generation of post-revolution young people, he remembers the stark contrast between home, a seeming time capsule of pre-revolutionary furniture, clothing and books, and the streets and schools of post-revolutionary Iran where the TinTin comics he kept in his bedroom were forbidden.

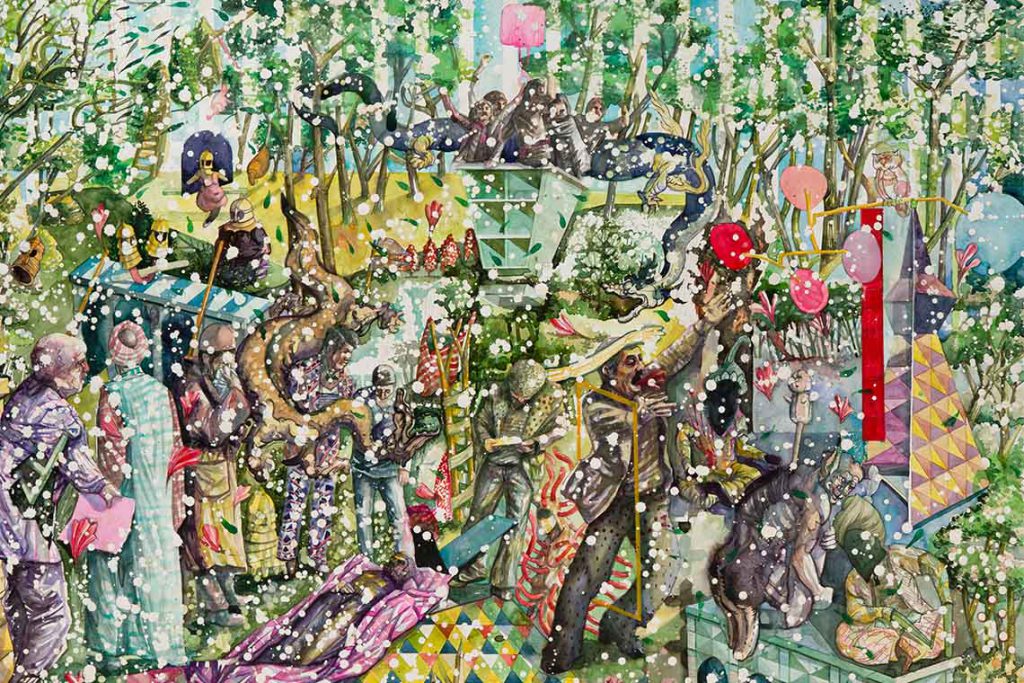

The artist sees home life and the outside world in Iran as a clash between real life and the story a society tells of itself, which is brought out in Samadzadegan’s key shift from acrylic and oil to watercolour in Heading Utopia. “Walter Benjamin says that you can hide history, but it cannot be erased,” he paraphrases. “When they give you an image of the revolution, it is of a kind of utopian future, but the history is changed to conceal the mistakes that people make, and the path toward that goal is changed, too. But with watercolour, there is no undoing, there is no painting over. You have to make decisions based on the accidents that happen and the mistakes that are made. By the end everything has changed.”

Crucially, there is a record of the changes. It’s as if, in some of the paintings, a modernist architectural element, for example, may not have been part of the original plan, and was added at the end. Or, that images of hooded revolutionary protesters or the suggestion of a religious figure were perhaps originally meant to be the focus. Instead, a cluster of trees, a piece of machinery or a swatch of brightly coloured traditional fabric took over. Rather than create an immersive environment populated by all of these, the paintings depict a series of dreamlike shifts from one point on the canvas to the next, never allowing a complete thought to fully materialise and thereby challenging the image’s capacity to represent concepts like truth, identity or history at all.

Watercolour makes possible the artist’s now recognisable chaotic interweaving of many seemingly disparate stories, and evokes the tradition of Persian miniature paintings, in which illustrations in storybooks depict several stories simultaneously. In many of his works, images of historical figures from Iranian history are depicted alongside a famous artist or writer, characters in medieval garb, modern Iranian soldiers, revolutionary protestors, strange creatures, livestock and architectural elements from different historical periods. With several focal points and multiple narratives, the decentralised works of Heading Utopiaforce the viewer to piece together their own stories from what is at hand.

Although these paintings are gorgeous – drenched in colour with rich imagery and depictions of natural beauty – the experience of viewing them can be frustrating at the same time, evocative as it is of the attempt one might make to piece together a true history from inadequate documents and artifacts. The subject matter in Samadzadegan’s paintings often indicates history, but refuses, as Moshari puts it, any devotion to historical fact. Like utopia, truth, in Samadzadegan’s mind, is unattainable.

History is littered with failed utopias, and Samadzadegan’s practice tracks this in paintings that include elements of love stories and stories of attempts to change the world for the better, as well as the hope that art is a context for righteousness and truth. As a teacher of art history, he is well aware of the historical claim that art is a representation of truth. “When I’m working with aesthetics, I’m always asking myself, ‘Am I witnessing truth?’,” he says. And yet, what he seems most concerned with is freedom rather than truth, inspired perhaps by the failed utopias of revolutionary states, with In the Penal Colony, After Kafka being just one example.

The Chronicle of Cenmar’s Descent in Kafka’s Castle, Samadzadegan’s dark, confusing 2018 installation in Tehran’s Mohsen Gallery, featured corridors and stairways leading to nowhere and decorated with illegible diagrams and photographs. The protagonist in Kafka’s novel, The Castle, arrives in a village governed by a mysterious administration. He continually tries to access state power, to find truth and to affect some change, but never succeeds, perpetually encountering barriers and never-ending bureaucracy. Yet, he does not leave the city.

“I could have moved away,” Samadzadegan says, “[and] emigrated to some other place, but I stayed in Iran, even though I’m not successful in finding the truth or changing anything as an artist. I’m just moving around, moving around, moving around and facing different stories and obstacles.” By placing unrelated images from different eras into new relationships, the paintings in Heading Utopiaare perhaps what remain of a search for an alternative route or another identity. “Painting lends itself well to reflection,” he has said. Samadzadegan’s search may very well be for the moment when there is no truth, and nothing in particular is being represented – the moment of freedom when we take what’s in front of us and make our own stories.