In his first survey exhibition at Jameel Arts Centre, Vikram Divecha showcases how his work aligning with the “found processes” of cities is really with their people and their lives within a fast-moving urbanity.

Short Circuits allows Vikram Divecha to consider the hours he has spent interacting with people over the past decade as part of his creative practice, and the number is difficult to comprehend, he says. After coming to work in the UAE, Divecha eventually quit his day job to pursue making art. With studio space being financially and logistically out of reach, he began “negotiating” with his urban environment to make work.

Mapping those negotiations, this exhibition documents Divecha’s engagement with the UAE’s cities, his participation in their communities, and his intervention in their systems, engaging with what he calls “found processes”. His work has a way of looking at what is overlooked: municipal gardening, urban demolition, roadmarking. “If I align myself with these processes, which do not need me because they are already ongoing in the city, and understand them, they become my material,” he explains.

Vikram Divecha. Degenerative Disarrangement, 2013. Interlock pavement bricks. Commissioned by Dubai Culture & Arts Authority.

Installation view of Short Circuits at Jameel Arts Centre. Photography by Daniella Baptista. Image courtesy of Art Jameel

Although not arranged chronologically, the works in the show reveal the development of an approach to cultural production that is rooted in time, value and labour. The bricks in Degenerative Disarrangement (2013), uprooted from a street during repairs, were acquired by Divecha who then hired masons to arrange them at a new site under the time constraints they are normally given to replace bricks after a repair.

The resulting irregular arrangement is an attempt to preserve the integrity of an original in a shifting environment, without additional resources. The parallels to Dubai and the many people who share the experience of coming there to work are obvious. Both the municipality and the UAE seem to have agreed, with Dubai’s Road and Transport Authority supporting the project, and the work being shown at the UAE Pavilion at the Venice Biennale.

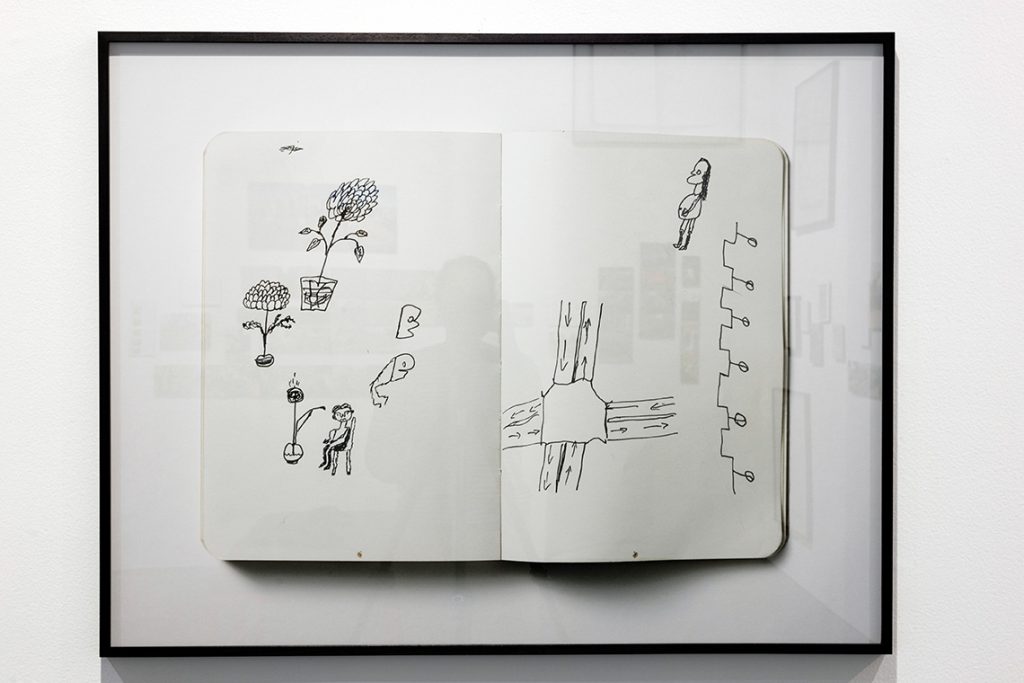

Value systems and groups of people with certain skill sets play a role in many of the works in Short Circuits. 2017’s Gardeners’ Sketchbooks collects drawings by municipal gardeners, who Divecha invited to imagine how they would design the waterfront hedges on which they toil in Sharjah, largely unseen and with no creative agency. As part of the project, their designs were implemented and maintained throughout the original exhibition of the work and for years afterward.

Divecha’s work often involves people from different walks of life as collaborators in cultural production, evoking questions over authorship pertinent to socio-economic frameworks that include the artworld. To do this, Divecha invests a great deal of time with people, asking them about what they’re doing, waiting for new questions to emerge – hanging out with them.

Tariq Mahmood Muhammad Riaz Ahmed, Sajad Hussain Bughio, Muhammad Shabbir Ahmad Din, Vikram Divecha, Shahid Ahmad Bashir Mahmood, Mohammed Mostafa Mohammed Junu Mia. Gardeners’ Sketchbooks, 2017. Installation view of Short Circuits at Jameel Arts Centre.

Photography by Daniella Baptista. Image courtesy of Art Jameel

For Boulder Plot, a 2014 work not included in Short Circuits, Divecha shadowed a rock-blasting engineer in the quarries of Fujairah and who was initially not clear about the project and Divecha’s intentions, the artist says. But several months into the project, Divecha noticed the engineer had hung up one of Divecha’s sketches from the quarry in his office, signifying some level of investment. A lot of the artist’s oeuvre is about engagement, and yet it doesn’t look like Pad Thai or other quintessential relational aesthetics works. “What I’m seeking is an aesthetic participation where those involved claim a stake in the work and are invested in this space that I’ve opened up”.

It’s also tempting to categorise works like Gardeners’ Sketchbooks as social practice, but it’s missing the activist elements of Theaster Gates’ urban renewal as artform, or Tania Bruguera’s work around the politics of immigration. As agents of change, Divecha’s works have a still smaller – but arguably more powerful – impact. “My presence,” he says, “changes not just my relationship with the people but also the relationship of the participants with their own site”.

There is another side to Divecha’s practice, which Short Circuits makes clear, bringing to life elements of urban life and the built environment. Rubbings from the walls of buildings slated for demolition,for example, show the fate befalling many structures in the rapidly developing and redeveloping UAE in Demolition Monoprints (2021).

Vikram Divecha. Corridor archway, 4th floor, Apt No.16, Khalifa building (Habib Bank building), Hisn Avenue (Bank Street), Al Shuwaiheen, Sharjah, 2021 and

Broken structural column, Tower 4, Mina Plaza Towers, Al Wudouh St, Al Meena, Abu Dhabi, 2021. From the Demolition Monoprints series. Printmaking ink on Legion acid-free rag paper. Installation view of Short Circuits at Jameel Arts Centre. Photography by Daniella Baptista. Image courtesy of Art Jameel

Survey exhibitions allow both audience and artist to look at a body of work across time, and Short Circuits reveals (to both, Divecha says) that his work has always been about people. “There’s nothing more beautiful in this world than meeting someone,” he observes, and the show’s most compelling works are those in which time the artist has spent with other people opens up a space for “a philosophical or aesthetic reflection within processes that are very much catering to what capital expects from them.”

Short Circuits takes its name from the phenomenon in electrical power where two points in a circuit that should not be connected, are connected. Whatever Divecha and his collaborators go through together during a project is “pointless in the production of capital”, he notes, and the value of this form of cultural production is, to be honest, difficult to capture in exhibitions. But, Divecha says, “that’s what I want to keep pursuing”. It is true, after all, that short circuits can cause the power source to be destroyed.