Raya Kassisieh explores what links and divides time and place in her solo show, So expansive, you and I become null, at Hunna Art Gallery in Kuwait.

“That space of spaciousness, so expansive, you and I become null. Where flesh comes apart, broken down, dissolved in matter until it turns light. A yearning to leave the body; the body, so lived-in…” writes Raya Kassisieh. Her poem, reflecting on a sensation of dissolution in water and the desire to disintegrate, lends a title to her solo exhibition at Hunna Art which oscillates throughout between a multitude of dualities and dichotomies. The “floating” that the poem alludes to, and the imagery of the body as a vessel of a life lived and remembered, manifest across the artist’s visual practice, characterised by performativity and endless iterations.

The exhibition can be read as both a love poem and a memorial. It reflects on lineage, heritage, land and loss as Kassisieh, who is of Palestinian heritage, mourns her late grandmother, who appears throughout in different guises. Claudette is introduced to the audience in Before I knew you (2024) as a sepia imprint surfacing suspended copper plates. This is the only instance when she appears with clarity; her form gradually fades across the threads that weave through the exhibition. In Do you see her? (2024) her ghostly figure is only discernible through her gaze, as she peers through a layer of foliage.

Here, Claudette’s image is superimposed onto a physical extension of her body – a vintage corset picked out by grandmother and granddaughter. In this attempt to tangibly frame a memory cherished by both, the delicate act of UV printing onto the article renders her likeness in a gently faded blur that mirrors both her transience and lingering presence, as well as the elusive nature of memory.

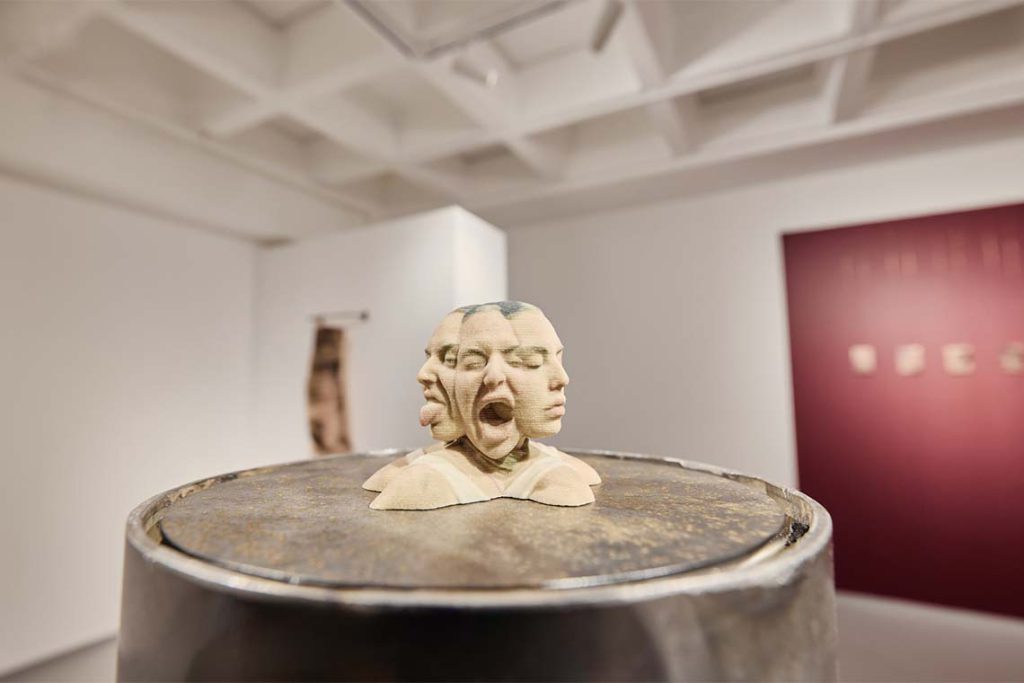

Kassisieh’s work seems to ask, how do you contain the uncontainable? Consciously drifting between the extremes of turmoil and softness, fragility and strength, mechanical precision and organically unbound expressions, she recognises it is only human nature to seek one in the other or to deny their inherent interconnectedness entirely. Her rotating self-portrait Bad Dreams (2024) embraces this with raw honesty, materialising a spectrum of fluctuating feelings and resonating with the dualities at play in the surrounding works. With eyes closed, the minuscule 3D-printed sculpture draws you in yet refuses confrontation. Kassisieh transforms an experience of vertigo into something human, posing a grounding point for emotions that often feel too vast, too tumultuous, to comprehend or inhibit.

The exhibition also navigates between figurative and abstract, with earlier pieces exploring more gestural articulations of the spiritual state. In Man-Hours (2020–22), created collectively during the pandemic, Kassisieh juxtaposes creation and erasure, marking an illegible stream of emotion in graphite. While this work is formed from destruction, her body-sized oil tapestries encompass the magnanimity of the natural world.

This broader eco-grief returns to the personal through the rose as a symbol of beauty and femininity, yet one that is ephemeral. The blooms Claudette holds in the copper montage reappear first as a steel bouquet, then as an oversized solitary rose. With an alluring yet daunting presence, the latter – You are more than the world to me, my eyes will never tire of seeing you (2024) – contemplates immortality and life at the edge of death, with curling metal thorns and surfaces tarnished with rust. Behind, a delicate swathe of silk organza drapes from a metal bar. Evoking the distortion and multiplicity present in Kassisieh’s self-portrait, Claudette reveals only fragments of the exhibition’s protagonist through a series of layered reflections.

In navigating these layers of grief, the deeply personal becomes a sorrowful mirror for the collective. Kassisieh’s mourning of a maternal figure, while holding on to the beauty of what remains, becomes an allegory for the larger loss of her people. Stacked, a mound of us (2024) reacts to a haunting image from Gaza of a father carrying his son’s remains in a plastic bag. While she honours her grandmother with thoughtful intent and softness, her rendering of these entangled, faceless limbs raises a further entangled question: what deems a life worthy of being remembered with grace?

Contrasting this confrontation is her trio of sculptures resting in a tender embrace, tucked behind a corner screen in a moment of vulnerability. Close, Closer and Closed (2024) sits in the liminal space between life and lifelessness, casting in bronze former states of Kassisieh – bodies she once carried and a physical existence now lost.

Through reiterative and performative explorations, Kassisieh meditates on the body’s capacity to articulate the abundant and the intangible: love, longing and loss. With associations of labour, the body then becomes a tool for practice and a medium for assertion. Her gestures – welding, pressing, moulding, mark-making – imbue her work with a physicality that mirrors its emotional depth. These distortions and magnifications dissolve the spheres of memory, emotion and form, and as curator Nadine Khalil notes, reflect that the act of becoming is also a gesture towards unravelling. The very impermanence of Kassisieh’s materials amplifies the fragility of memory, which resists being wholly captured. It is in these nuances between preservation and dissolution that lies the sublime: a boundless longing that transcends through the artist’s body and work.