Curated by Dr Omar Kholeif, this nearly over-abundant group show emerges from a love for London as many of us know it: a meeting point and home.

When you look up the curator Dr Omar Kholeif online, he comes up as part-Sudanese, part-Egyptian. “I’m a British citizen and that’s the only passport I have,” he says. “Where is the context of the city that shaped me, that could conquer me, where I studied and lived, the place where art, artists and my mentors moved?” Kholeif frames his latest curatorial project – the group exhibition Finding My Blue Sky at Lisson Gallery – as a love letter to London, a city he has loved and loved in for over 20 years. The show is an emotional map, both charting and generating the “constellation” of lines along which Kholeif has worked, met and desired things and people here. He invites his audience to do the same: visualise their own maps of this complex city, with themselves as the compass.

On 12 May this year, British Prime Minister Keir Starmer announced a “Plan for Change”. He promised to end the UK’s “failed experiment in open borders” with policies aimed at reducing immigration and including doubling the wait for naturalisation. It is the kind of masculine, tightening-fist, rightward move that is becoming ever more commonplace globally, and it runs counter to Kholeif’s ambitions at Lisson. His are deliberately soft, searching, poetic enquiries, one could even say feminine – more than 60 per cent of the artists in the show are women – and with a fluid, sensuous flow. They are brought together through the hundreds of tiny gossamer threads that web us into communities of immigrants, travellers and citizens, each and all dreaming of a satisfying click of belonging. Or a “blue sky” – so democratic, in that we all see it, and yet also utopic in that each of us always perceives something else.

Spanning both the gallery’s spaces (a short walk apart) in the Edgware Road area of northwest London, Finding My Blue Sky features more than 20 artists of different origins and generations, including Huguette Caland, Simone Fattal, Michael Rakowitz, Barbara Walker, Anuar Khalifi, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian and Celia Hempton. The windows are entirely uncovered, baring the art to the street, which I have to walk on in order to experience the show in full. To Kholeif, Edgware Road is a microcosm of London’s – and the UK’s – plural modernity. With clouds of shisha cafes at one end to one of the UK’s largest private psychiatric hospitals at another, and from Oxbridge prep schools to the diverse Arabic-speaking community that lives locally, including some who have lived in the same social housing blocks since they were children. Edgware Road visibly prods us to accept how, in the postcolonial aftermath, this country has irreversibly changed. Lisson has never moved from the area in all its decades. When conceiving the show, Kholeif thought: “Why does the gallery not speak to the street?”

So, the show begins on the road. Lubaina Himid presents street murals portraying East African kanga garments, made from fabrics woven with looped text. The murals are both text and textile: Himid’s conversations with Kholeif, influential to the show’s conception, explored memories of accompanying her textile designer mother to colonial independence ceremonies at various African embassies in 1960s England. Despite that heavy heritage, the murals appear tender, with a childish innocence, a buoyant nod to the school right opposite the gallery. Kholeif points at a spot there and says, “That’s where I met Lawrence Abu Hamdan for the first time”.

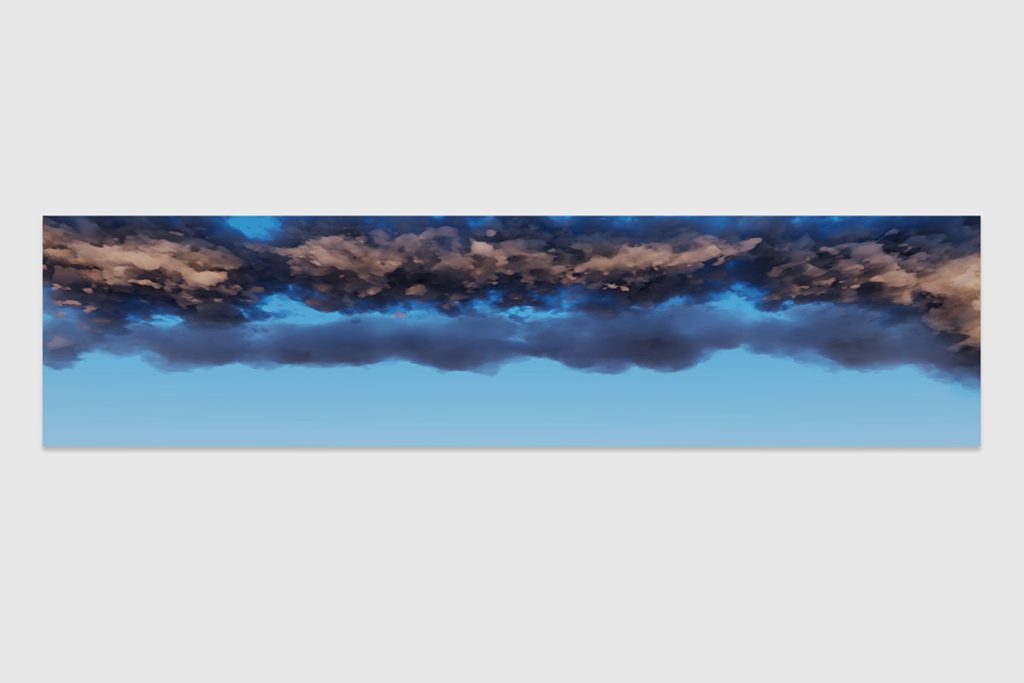

Image courtesy of the artist and Lisson Gallery

Abu Hamdan’s Air Conditioning (2022) resembles a grave Turneresque painting, yet is a photograph made from aggregate open-source data on every violation of Lebanese airspace by Israeli military aircraft during 2007–21. Although it holds a sombre museum-like air, it also feels uncomfortable and uncanny in a way that only resonates with living in our particular era of modernity – where its dark corpulent clouds evoke daily iPhone images of warfare, before an incoming thunderstorm. Abu Hamdan’s aesthetics belie a focused political complaint, a format exercised with varying degrees of intensity by other works.

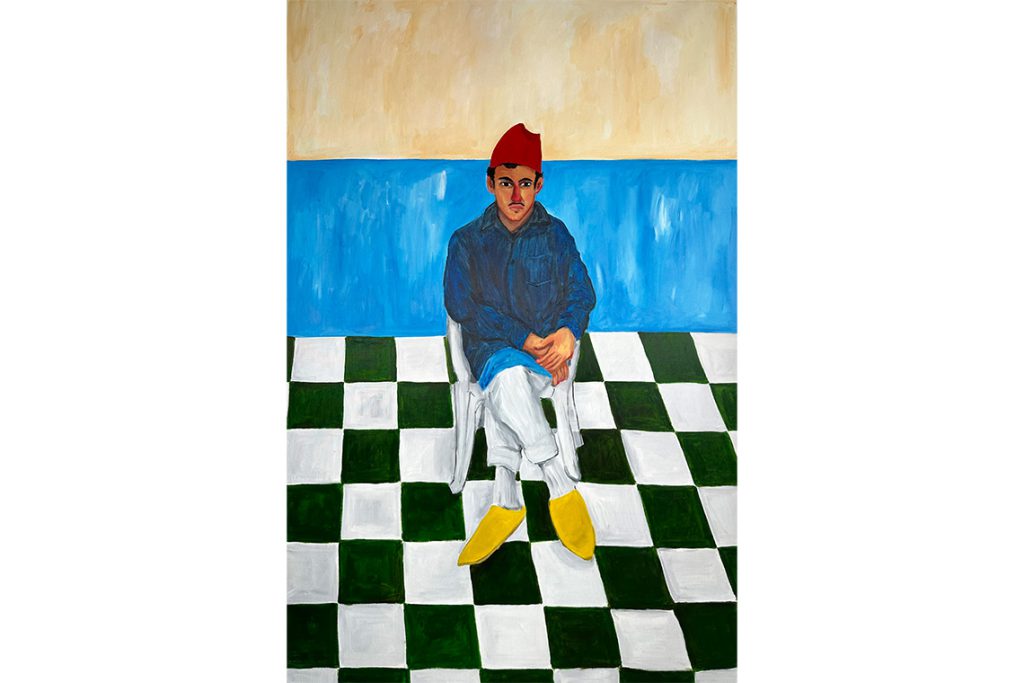

For instance, a stunning new triptych, Aqiqah or aqeeqah (2024), by Spanish Moroccan painter and Kholeif’s dear friend Anuar Khalifi, plays on the Holy Trinity. More than subversion or representation, however, the paintings are just so enticing – the male subjects’ enigmatic expressions, their vivid coloured garments, chequerboard floors upon which a rivulet of blood descends from a slaughtered goat. In another work, a boy in a Manchester United jersey sits on his bed, contemplative; his white djellaba hangs in the background, near a green prayer mat, a thick ‘ethnic blanket’ spread behind him, so richly rendered you can nearly feel its characteristically dense, soft thickness. I text a picture to my British-Algerian friend and she responds: “Me”.

The show shines when it leans into its interest in the corporeal. Huguette Caland’s erotic yet melancholy Pink Feeling Blue (1973) is arguably the hotspot (Kholeif has just released a new critical biography of the artist and is evidently besotted) – its heated lilac rubs against the blues of a candle flame. The work’s sensuousness and depth resonate in the centrifugal, curving, abstract or spiralling forms found in works by Fattal, Saloua Raouda Choucair and the undersung Portuguese artist Luísa Correia Pereira. What sticks with me most is Hrair Sarkissian’s previously unseen photo series La Peau (2025) (meaning “the skin”), which looks at the body so closely and with such care that it abstracts it into something larger and entirely different – a desert landscape.

The Arabic title of the exhibition translates to “What is the World that you Dream of?” It is a type of enquiry that more and more institutions and shows are ossifying into a trend, leaning into ideas of rebuilding, reimagining and speculative practices that are, perhaps, just desperate to create something new in the midst of reigning dystopia. Where Finding My Blue Sky slightly deviates is that it proffers a more permeable, honeycomb-like directive (swatches of text like “Find your soft landing” encourage the audience’s interpretive agency). It puts forward an “aesthetic politics” that begins, like charity, in the home – our neighbourhoods, friendships, collaborations, encounters and years of accumulated memories and spaces.