The artist speaks about her tongue-in-cheek approach to a multidisciplinary practice that seeks to chronicle lost histories and redefine the vision of the UAE’s past from a contemporary perspective.

Canvas: You recently showed Once Upon a Pirate Coast (2024) at Abu Dhabi Art, in the Beyond Emerging Artists section. How do the pieces prompt a rethinking of historical archives and memories?

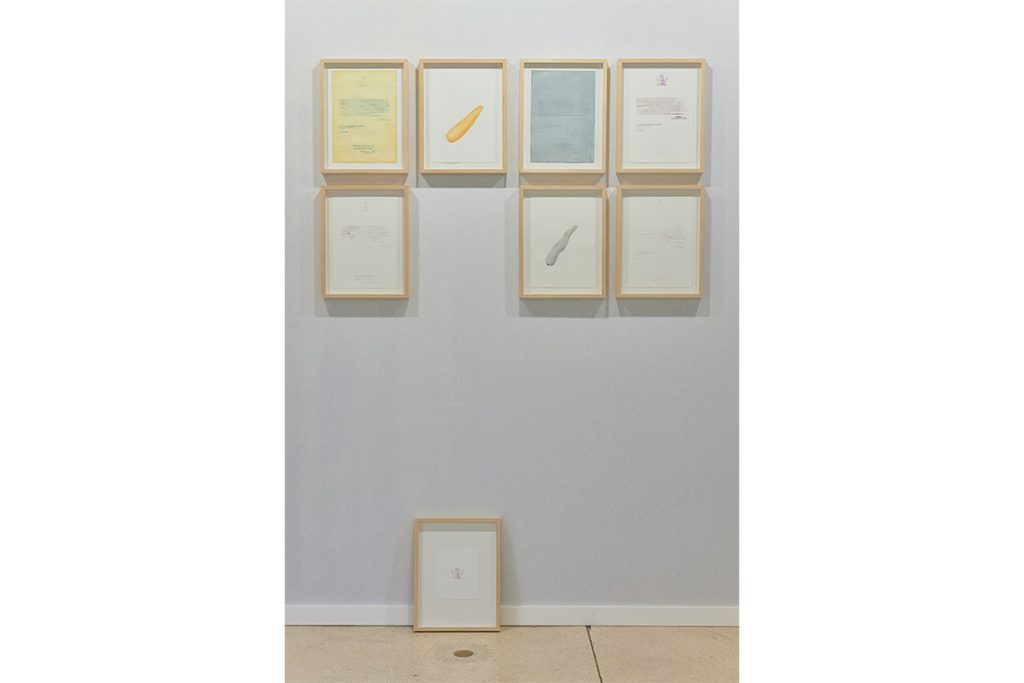

Fatma Al Ali: This installation is based on my research into the British presence in the UAE and consists of three works. Of Ships, Sails and Misguided Labels (2024) features frames with text and images that delve into the British campaign against the city of Ras Al Khaimah and their lies about a pirate presence. I added a tone of playfulness to it with the words: “Row, row, row your boat aggressively to our shore. Claim it’s piracy, go on and start a war.” The central coin installation, I Picked up a Coin and Heard a Whisper (2024), was accompanied by an audio piece, the voice of the land reclaiming the narrative. I Read Their Words, but I Heard my Own (2024) is a series of tablets made from desert sand, beach sand and seawater, mixed and bonded. They are presented in pairs, with excerpts from Arab and British newspaper articles overlaid to tell two sides of the same story: the British resources, which refer to the place as “the pirate coast”, and the Arabian resources, with information about the environment, fishing and people living their lives and trying to survive the harsh environment.

How does language fit into your practice, and what impact does it have when looking back on these events, particularly with such a satirical, playful tone?

When dealing with history, I am surrounded by language. I wanted to present the works similarly to how I first encountered the history. For example, reading about the pirates was amusing, something you would hear about in childhood stories. I wanted to add that initial playfulness. Also, with the written history of the UAE being very limited or skewed towards other perspectives, I am reclaiming that narrative, but in a playful way. I also focused on the sculptural elements of materiality and tension. These concepts stayed with me, even as I started delving more into the archives. I wanted both to showcase this idea that there is a rich history in the UAE that people are unaware of and bring it forth to Emiratis of my generation in a digestible way. It’s a reintroduction to history. We are focused so much on the future, but we should know our past.

Can you describe your approach to using archives in your work?

I started by collecting as many books and magazines as possible. I also have access to the National Archive and subscribe to the British Newspaper Archive. I try to read as much as possible from varied sources and slowly start shaping a narrative in my head. I’m trying to understand the past from a contemporary, individual perspective. I always keep tabs in my head for things to research in the future.

How does working with historical archives enable you to shape the memory of the past in a particular way?

The UAE is in a very unique situation of rapid change. I have access to memories from my parents and through my grandparents. Their perspective on things is quite mind-blowing. I want to record as much as possible of that oral history, otherwise it might be lost in time. I also have the memory of written history from another perspective. When I try to fact-check, I go to my dad and ask him for his perspective on what happened, and it’s completely different from the British version of history. It’s essentially two faces of the same narrative, and trying to digest those from this contemporary viewpoint is interesting.

What approach do you take when addressing topics such as colonialism and occupation and how these influences impact archiving and documentation? Something that immediately comes to mind is the purple carrot in your work It’s not easy to persuade Arabs to do this (2023).

This is a funny part of history. I came across this document on introducing different fruits and vegetables to the UAE. One specific paragraph was about carrots. The language itself was very amusing, and said something along the lines of “the European carrot is far superior, it’s very hard to convince Arabs to grow them, so let’s try and make juice out of it and sell it to them. Maybe then they will enjoy the juice, and then they will enjoy the orange carrot”.

For part of the work, I created two videos. In one of them, I have the orange carrot in one hand and the purple in the other. I wanted to act on the carrots, so I would cut them, measure them, create juice out of them or try to stain the orange carrot with purple juice. The more I did, the more absurd it got. At one point, I took acrylic purple paint and painted over the orange carrot to reclaim it, but it would still be orange when I cut into it. This process builds up until the end of the video, where I sneak into a vegetable marketplace and put the purple carrots where the orange carrots are supposed to be.

Your work is based not only on collective memories, but also on personal ones. Is My Mother Told Me Not To Collect Bricks (2020) an example of a more personal approach?

At the time I was reflecting on social norms. I visualised these norms, or barriers, almost as a wall preventing something. Then I started to think about the possibility of this metaphorical wall not being solid or strong. The title comes from my mom telling me not to collect bricks, which ties into ideas of social norms that are not true to who I am personally. I was playing a lot with opposition, while also trying to create some tension within the viewer. The bricks are made out of latex, which creates a feeling that they might change and shift, fall or crash. I was thinking of skin, and what would happen if you changed it, if you wore another skin on top of your own?

This interview first appeared in Canvas 116: Time After Time