Stéphanie Saadé’s current exhibition addresses themes of dislocation, memory and reconstruction using architectural interventions and everyday materials that connect individual and collective histories.

Stéphanie Saadé’s latest exhibition, The Encounter of the First and Last Particles of Dust, is currently on show at the Sursock Museum. The location of the show is particularly poignant; the 4 August 2020 Beirut port explosion, which killed 218 people and destroyed more than 70,000 homes, resulted in the destruction of much of the museum. An extensive restoration project thankfully saw the reopening of the Sursock three years later. Today, Saadé’s exhibition, which touches on themes of spatial memory, displacement and recomposition, aptly draws on the museum’s own history alongside her personal experience.

The themes of displacement and dislocation are made immediately obvious through a site-specific intervention titled Traversée des états (Crossing States) (2024) . The work covers the floor of the Sursock’s Twin Galleries, with visitors immediately stepping onto a full-scale floor replication of the artist’s family home. Speckled terrazzo is interspersed with bright white tiles, brown ceramics and plush navy carpet. Grey tiles haphazardly border parts of the inlays, creating a muddled and disorientating effect; the very ground beneath our feet is shifting in a matter of steps. Through the installation, Saadé mirrors the sudden change in surroundings experienced during dislocation and displacement.

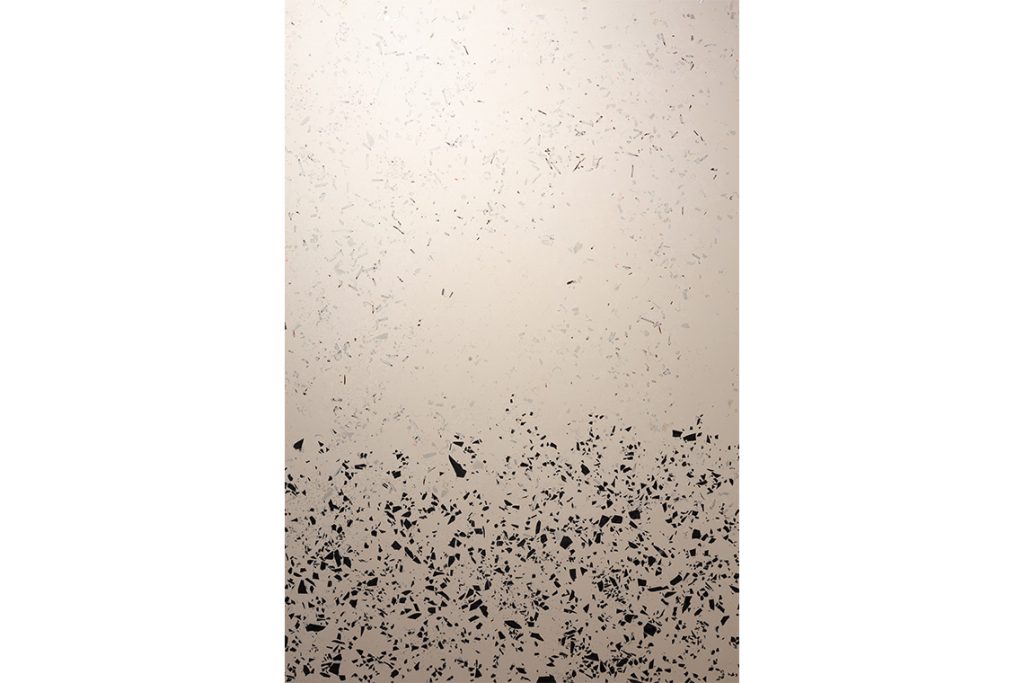

Two separate pieces are suspended above this floor installation as the final part of the Crossing States collection (2024). Here, terrazzo appears again – speckled flecks of black, brown and grey appear jumbled against a harsh white background. Made by combining a cement base with a mixture of ground materials, terrazzo is either poured by hand or pre-cast in blocks. In both scenarios, one cannot control how the ground materials will fall. The random pattern of the terrazzo seems to point to the lack of control that one can often feel in periods of crisis.

Upon closer inspection, these final terrazzo panels also contain albums by the iconic Lebanese singer Fairuz. Cassettes, vinyls and CDs have been broken up and interspersed in fragments throughout the concrete. The effect instantly invokes the notes and melodies of her songs, which have become well-loved throughout the country. By incorporating Fairuz through splintered shreds, Saadé creates an uneasy sense of familiarity and dislocation.

Crossing States is softly broken up by beige curtains salvaged from Saadé’s childhood home. These lay in soft pools across the floor, their fluid materiality allowing visitors to traverse freely. As a result, we at once feel welcomed into a familiar environment, further aiding the idea that we are in the artist’s own home. The curtains are embroidered with sloping, occasionally jagged, white lines. These curving routes represent the 37 trajectories that the artist would routinely take while travelling through Lebanon during and in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War. They map journeys to visit friends, family, the local school and sports clubs. We are faced with a vivid contrast: the benign nature of these everyday trips and the context of the Civil War taking place in Lebanon.

These muddled childhood memories are further encapsulated by Golden Memories (2015–18). On first view, visitors see a framed piece of shimmering gold leaf, seemingly hopeful and bright. In reality, the reflection of the gold obscures a childhood photograph of the artist. Visitors are instantly faced with the irony and cynicism of the piece, with the mirrored surface also inviting them to project their own ‘Golden Memories’ onto the framed leaf. Both abstract and figurative, the piece cleverly reminds us how easily memories are obscured by the passage of time.

Other works in the exhibition are centred around the artist’s more recent experiences. The 2019 Revolution, Covid-19 pandemic, economic crisis and Beirut port blast – which destroyed Saadé’s studio – led to the artist relocating to France, where she now works from her domestic apartment in Paris. We see her piece together the different aspects of her life in Petits Papiers (2022). A series of seven framed pieces showcase miscellaneous items – maps, stickers, tags from purchased items, flight tickets. Viewers witness the growth of her child as the sizes of clothing tags get ever larger. Elsewhere, receipts depict the price of items changing rapidly, highlighting the deterioration of the Lebanese lira. Through these discarded scraps, Saadé encapsulates the monumental shifts underway in her life during this period.

Themes of dislocation and reconstruction are explored further in a series of calligrams. Words are scribbled repeatedly in spindly black script, appearing both messy and painstakingly neat all at once. Different languages are used, pointing towards displacement and a shared universal experience. Occasionally the writing fades or jolts slightly as the artist tires, reminding us of the nature of handwriting; now widely considered obsolete, calligraphy is tirelessly at the mercy of human error. Once formed, it cannot be instantly erased. Through these calligrams, visitors are reminded of the pain involved with recomposition and the value of communication.

Attached to a stark white wall at one end of the exhibition is Scarred Object (2013). From afar, the work appears as a metal bar. Closer up, the smooth reflective surface is interrupted by puddles of metal. These sections, rough and irregular, represent where the metal has been cut and welded back together. Simple, yet poignant, Scarred Object points to the key themes of the exhibition – dislocation, resilience and recomposition. Through The Encounter of the First and Last Particles of Dust, Saadé – in her typical conceptual and poetic manner – manages to explore her personal lived experience while adeptly inviting the viewer to share their own.

The Encounter of the First and Last Particles of Dust runs until 15 January 2026