Body of Evidence, Iranian artist Shirin Neshat’s solo exhibition in Milan is a rich, immersive experience which jumps between the many-layered visuals and sounds of the artist’s universe, in works produced over a decades-long career.

Immediately upon entering the first room of Body of Evidence, Shirin Neshat’s solo exhibition in Milan’s PAC Padiglione d’Arte Contemporanea, the visitor is confronted with noise, giant visuals and intent. There is no gentle introduction to the subject here, just the room-filling moving image diptych that is Fervor (2000), which contains many of Neshat’s celebrated motifs. It is not, however, a film one may expect to open a large retrospective exhibition, being a work from the middle of Neshat’s career and also the final part of a trilogy exploring Iran’s Islamic society

Neshat has had a hand in the curation of the exhibition alongside Diego Sileo and Beatrice Benedetti, and was keen that it would not be a chronological journey through three decades of work. It is instead more of an overlapping, clashing, crossfiring full-frontal installation, in which the visitor is not handheld and led through the story but rather pushed into the middle of a complex landscape to find their own way. It is an approach that would not suit most artists, but fits Neshat’s work well and particularly suits the non-traditional gallery architecture of PAC.

PAC is not an easy space to curate. A series of four open-sided rooms hangs off a large central atrium, with a sunken corridor level along the opposite side. Steps lead to an overlooking balcony, another long corridor space and two further small galleries. There is no logical sequence of navigation through, and white-wall hanging space is at a premium. The large, central open space with visual and sonic spill from all sides means it is also not well suited to the quiet, sound-insulated, contemplative displays that form traditional, narrative-focused, durational, moving image-led exhibitions.

Fervor introduces the visitor to Neshat’s work, and if the visitor stays for the full ten minutes they will encounter strategies and ideas that recur wherever their route takes them after. Narrative led, and shot with a cinematographic eye totally in control, there are two main protagonists, a man and a woman, who by chance encounter one another in an otherwise empty urban space. With the silent tension of Italian neorealism, and silently speaking to the gender rights imbalance of Iran – where Neshat is from and which is central to her practice – we observe a simmering space between.

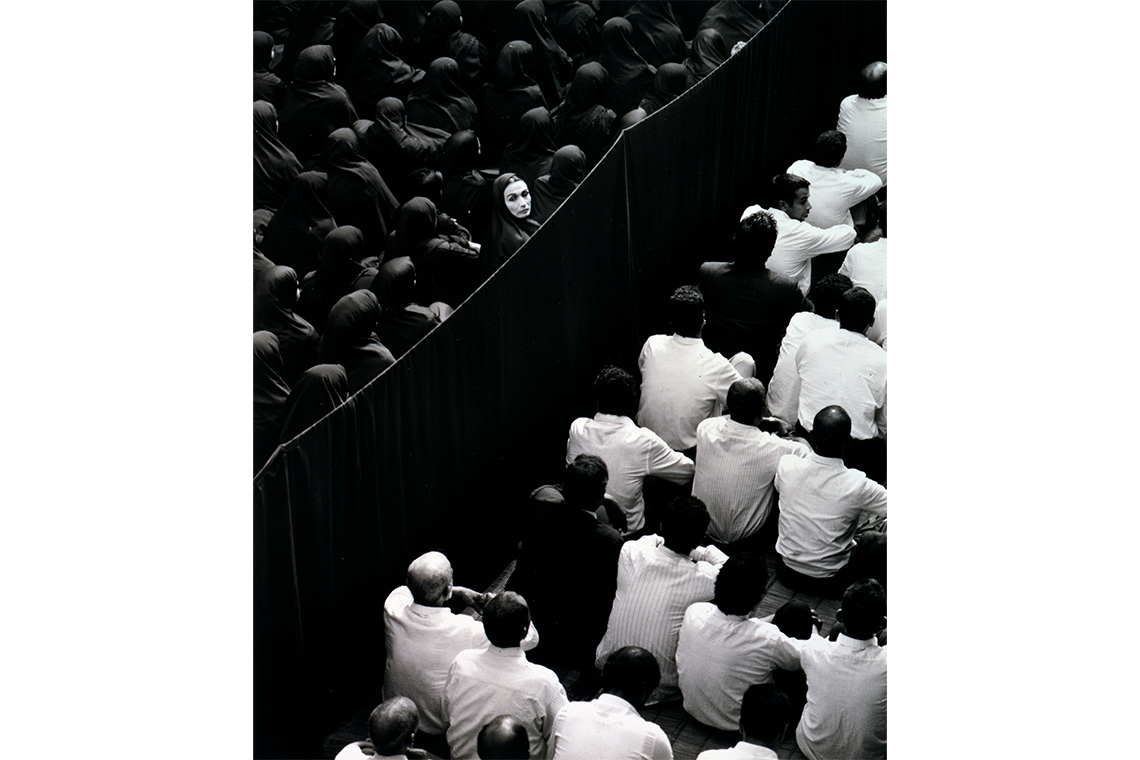

Neshat’s directing uses the split-screen and split-sound with rich control. Each side follows one of the two characters as, after that momentary encounter, both are present in a crowd listening to a speaker recounting the Koranic parable of Zolikha and Youssef – she in a crowd of black-veiled women, he in crowd of white-shirted men, a large black drape dividing them. While both are present, listening to a tale rooted in the sin of desire, they are visibly unaware and yet perhaps cognitive of each other’s presence. We, witnessing both experiences, live in an uneasy gap of hope, desire and impossibility. We are within both interiors simultaneously.

Sound is critical to Neshat’s practice. In Fervor it slips between left and right worlds – there is delay, reverberation, and we are aurally reminded of the unease and imbalance of the situation. After leaving Fervor, sound remains important to the curation, with noise leaking through black curtains from each adjacent gallery, teasing and inviting. Normally, this sound leak would be frustrating, but here it intrigues. In one space, Roja (2016) delivers a dreamlike experience between Iran and the USA, another diptych here drawing from surrealist filmmaking to speak to Neshat’s psychological experiences adapting to American culture after moving to California in 1975. She arrived there to study after leaving the Tehran Catholic boarding school that her father had placed her in after her childhood in Qazvin, north-western Iran. He wanted her, and her siblings, to have a worldly outlook while retaining Muslim values, and after graduating from Berkeley she spent many years doing just that. Art was not her primary route until the 1990s, since when a defining patience and singular desire have become the hallmark of her work.

Roja speaks to this duality and displacement, of childhood and adulthood homes. Next door, the twin screens of Land of Dreams (2019) builds on the realism and dreamscapes of other works. A female Iranian photographer visits homes in New Mexico under the pretence of being an art student taking portraits – she asks the subjects about their recent dreams while making the photographs. The other screen presents a different angle, where the photographer is tasked by an unknown organisation to harvest dreams. This vantage point takes us away from realism into a sci-fi mind-inhabitation, exploring similarities between Iranian and American repressive regimes and social structures.

The other spaces also offer a battering of visual, sonic, theoretical and political ideas. Turbulent (1998) and Rapture (1999) explore gender differentials in Islamic society, one in intimate and rich song, the other in expansive, repressive landscape. Upstairs, Soliloquy (1999) and Passage (2001) play in neighbouring rooms. The latter, a collaboration with American composer Philip Glass, uncannily navigates death rituals, again as a study of landscape and gender, and once more with stunning cinematography from a place richly aware of both photography and film and of the space between the two disciplines. Soliloquy returns to exile, two screens, one East, one West. Neshat is in both, and between both, wandering urban landscapes, neither home, neither elsewhere, both the same, both unreconcilably different. To watch all the films one-by-one would be a lot, perhaps too much, but to bounce between and find a personal landscape that connects them all is a rich way to engage.

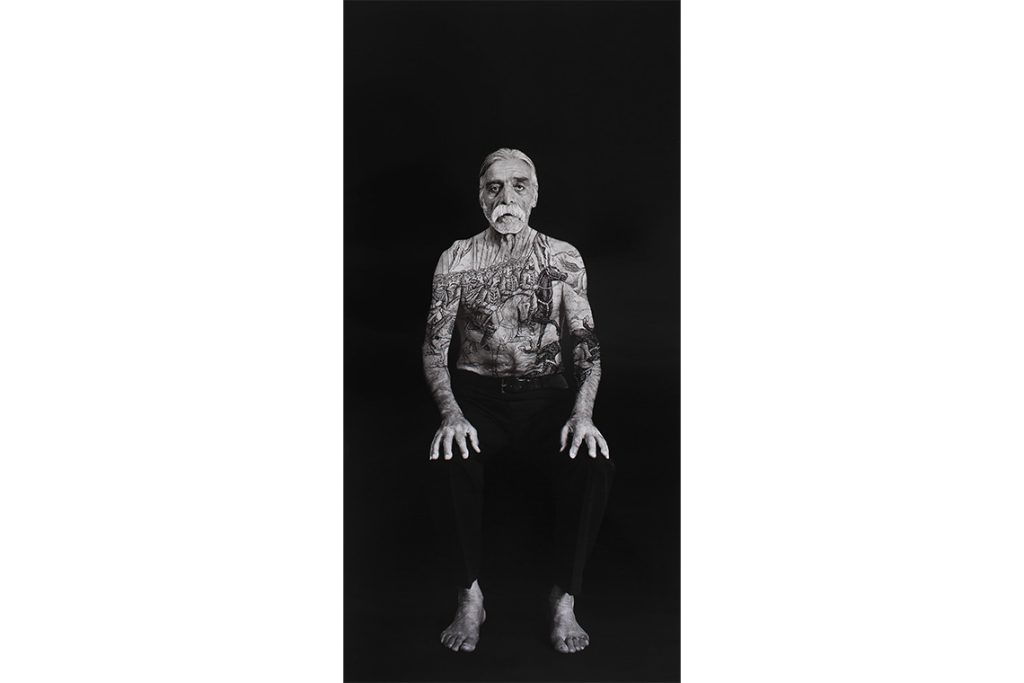

Copyright Shirin Neshat. Image courtesy of the artist, Gladstone Gallery and Noirmontartproduction

The spaces between – two long walls on the sunken and balcony levels and a half-open room – present Neshat’s still-photography work and act as welcome pause between moving images, albeit one where sound leaks from films remind us of ongoing trauma, psychology, desire and despair elsewhere. A salon-hang of photographs of women’s bodies as spaces of violence and desire relate to an adjacent film The Fury (2023), considering sexualised violence on female prisoners in the Islamic Republic of Iran, who after release are unable to contend with the physical and emotional abuse wrought upon them.

Downstairs, in photographs from The Book of Kings (2012), Neshat has written calligraphic texts onto bodies, a work after the Iranian Green Movement, thinking around the role of the body, division of future ideologies, and hope. On the balcony level, Women of Allah (1993–97) is a series of photographs made on her first return to Iran, 16 years after leaving for the States – and the most political, violent 16 years. Here, texts by female Iranian writers caress the parts of bodies left visible outside of the chādor. As with the films, the silence is loud – and the silencing even louder.

With a practice covering photography, art film, feature-length film and recently opera (her Aida will be restaged at Paris Opera House later this year), it can be complicated to create a coherent curation of Neshat’s work, but PAC’s approach works with the selection of works and their unique space. With a non-didactic curation and route through, the visitor is invited to engage at their own pace and approach, a confident and generous gesture which allows space for the works to speak to us and one another.