Curated by Anlam Arslanoglu de Coster, The Volcano Lover at Galerist, delves deep into the paradox of the volcano – both a force of ruin and a source of renewal – in works from the eighteenth century to today.

Black volcanic ash spirals miles up into the sky, thwarting the explorers aboard the Australia-bound HMS Aurora, whose nautical chart obsessively calculates their abortive attempt to reach the virgin island on the distant horizon.

This is the vivid world that Turkish artist Ahmet Doğu İpek has imagined in Caecus and Albino (2025) for The Volcano Lover, a group exhibition currently showing at the Istanbul gallery Galerist. The charcoal-on-paper work spanning three metres is a fastidiously handmade document of a fictional 1805 scientific expedition to the Southern Seas and its encounter with a cataclysmic rupture in the Earth’s surface.

Artists from J M W Turner to Andy Warhol have been inspired by volcanoes, and the artists invited by curator Anlam Arslanoglu de Coster to participate in The Volcano Lover share the “fascination with the monster,” she says. “The show digs into how contemporary artists feel about nature, its power and myths at a time of technological advancement, from AI to trips to the Moon and Mars.”

The show takes its name from Susan Sontag’s eponymous 1992 historical novel. Set in the late 1700s, the story of the real-life British ambassador in Naples, William Hamilton, his wife Emma and her lover Horatio Nelson takes place against the backdrop of Mount Vesuvius, the smouldering mountain that symbolises both the characters’ multitudes and the tumult at the twilight of the Age of Enlightenment.

Just as artists turned to classicism in the late 1700s, de Coster sees artists in our own time of transition burrowing into the past. “The end of the eighteenth century is quite similar to our era, with its social upheaval and political conflict,” she notes. “Artists today are also searching for the answers in the past, but many of the artists here are going deeper into prehistory.”

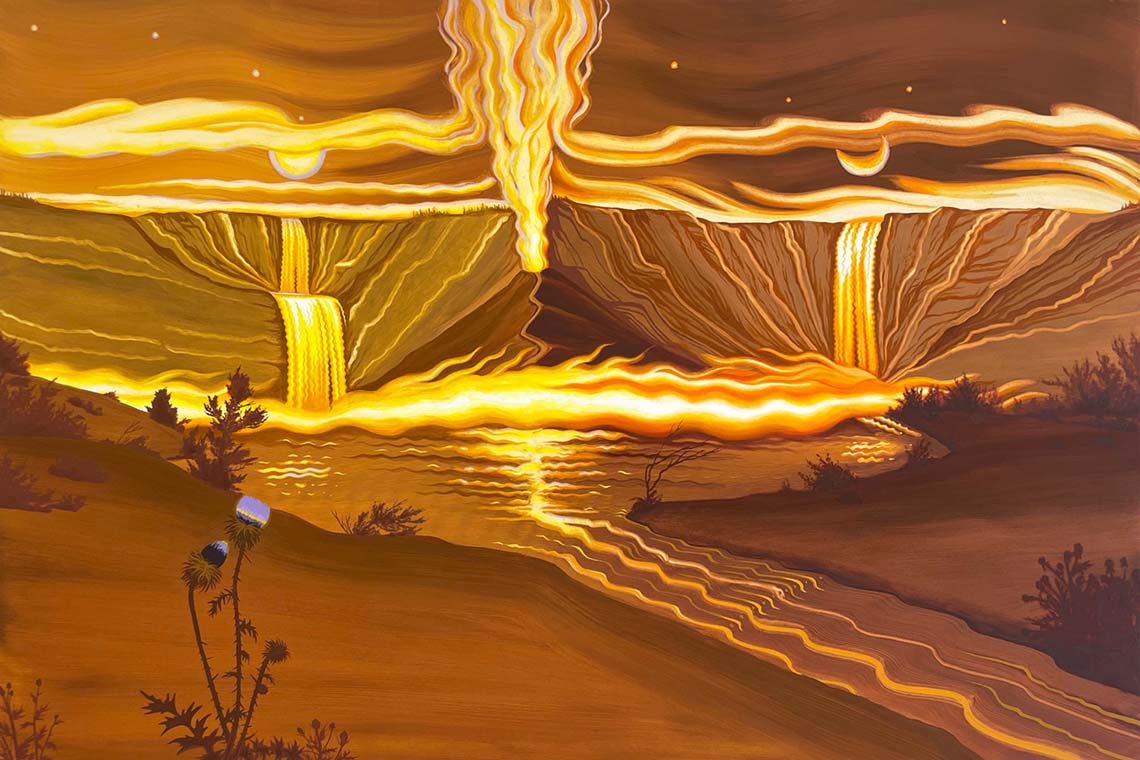

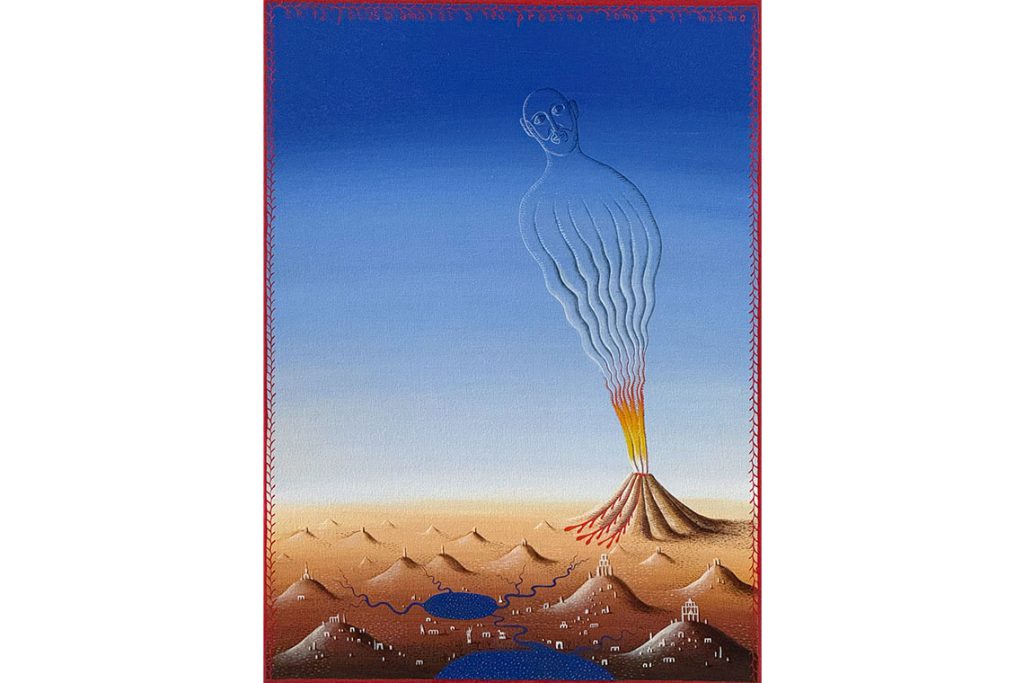

Los Angeles-based artist Jen Hitchings’s fiery 24 Hours (Yellowstone, with milkweed thistles), an oil painting on panel from 2024, seems to reimagine the corner of Wyoming in its primordial state billions of years ago. In the self-portrait No more, no less (2025), Brazilian painter Alex Červený emerges as a plume of smoke from the mouth of a volcano with the exhortation to love others as you love yourself.

Ceramicist Elif Uras abandoned her usual technique of slipcasting to work at the wheel to make stoneware plates depicting mythical mountains whose magma is expelled by female creatures deep within. Her statuette Kundalini II (2025), reminiscent of the bulbous Anatolian goddess form, bears a chamber at its centre from which the smoke of incense travels through a small chimney. “For me, the volcano was always a female power. Volcanoes are not just a destructive force, but nature’s way of regenerating itself, to give way to fertile ground,” Uras points out.

They are among the 39 artists exhibiting in The Volcano Lover, whose curatorial depth is on par with a museum show. De Coster credits Galerist’s programme of staging a large-scale exhibition each season to bring together artists it represents with others working around the world. These curatorial exhibitions are meant to nourish artistic exchange across “different generations and geographies,” says gallery director Müge Çubukçu.

The Volcano Lover can be “read through a dual narrative,” Çubukçu adds. “Seemingly opposing concepts – such as destruction and regeneration, masculine and feminine energy, passion and composure, individual and collective memory – are actually intertwined.”

The show is punctuated by photographs, including landscapes left behind by ancient volcanoes, taken by the late Yıldız Moran during her twentieth-century travels across Turkey. Her image of the frescoes of a rock-cut Byzantine church is in direct dialogue with Hera Büyüktaşcıyan’s four sculptural collages, Icons for Tired Skin (2024 and 2025), in which scraps of industrial carpet frame photos taken of the walls of Istanbul’s often neglected churches.

“The carpet has become an element that I frequently use in my practice, but in recent years has enabled me to examine the concept I call ‘surface tension’ more deeply,” says Büyüktaşcıyan, who works in Istanbul. “Damages on their surfaces caused by political power shifts and xenophobia are the reminder of the unwanted.”

The exhibition meanders through Galerist, which is housed in a grand nineteenth-century apartment overlooking the Golden Horn, to a room that serves as the study for the aspiring volcanologist and antiquarian Hamilton, who collected classical pottery, sculpture and mosaics. Alongside books and ephemera are historical works, including engravings by the eighteenth-century painter Pietro Fabris that illustrate Hamilton’s research at Pompeii and other excavations.

A portrait of Lady Hamilton mourning the death of the naval hero Lord Nelson by Friedrich Rehberg (c.1805) is a reminder that the collector Hamilton acquired Emma in exchange for settling the debts of her former lover after falling in love with her portrait, which now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in London. In Sontag’s novel, “Vesuvius is a metaphor for love and repressed desire and how the act of collecting is both futile and important,” says de Coster.

Her own preoccupation with volcanoes first took hold when de Coster visited Naples and Pompeii as a teenager. Creating the domestic space at the end of the show is meant to convey that the volcano “is not just a dry, rational exhibition subject. It’s an erupting passion that invades your life,” she confesses.