This year’s edition of Noor Riyadh, while smaller than previous iterations, shined bright with ambition, setting world records and most importantly, providing a space for local communities to come together.

Winter in the Northern hemisphere is the season of the Pleiades, a star cluster known regionally as al thuraya. Made up of young, hot stars, it is distinctive for its bright blue glow and is considered one of the easiest asterisms to see with the naked eye. As such it was particularly important for navigation, as well as in the almanacs that farmers followed to guide their plantings and harvests. For the fourth Noor Riyadh (ended 14 December), curated by Dr Effat Fadag and Alfredo Cramerotti, it inspires the theme of Light Years Apart, or ‘between the ground (al thara) and the stars (al thuraya)’ in its Arabic version.

With its tranquil riverine location, Wadi Hanifa felt like the strongest site. Many works spoke to environmental degradation, most poignantly in Stanza’s red-lit, gasping tree Out of Breath: A Life Support Machine (2021). Other highlights included a pair of monumental installations that were effective in their spare simplicity. While Saeed Gamhawi’s Ala Wath Al Nega (2024) is an austere, if somewhat schmaltzy tribute to Saudi unification, it is both formally interesting – an enoki bunch of streetlights – and compelling in the way it visually invokes hyper-surveillance. Romain Tardy’s The Great Indecision Council (2018), meanwhile, is a large ticker tape of an arena that spells out our most frequently searched words, although given the whiplash pace of change in KSA in the time since the work was made, I can’t help wondering how different a more localised version made today might be.

Of course, there were still two new Guinness World Records set, bringing Noor Riyadh’s total to 14. The first is for the Longest Distance Covered by a Laser Light in a Laser Show, from Chris Levine’s Higher Power (2024). Here, a powerful purple laser installed atop the Al-Faisaliah Tower sends four beams out into the stars, pulsating with the work’s title, and the word salam, or peace, in Morse code. Visible across the city, the beams are aligned with the mystical ley lines that connect Earth’s ancient monuments and are believed to be conduits of significant magnetic and psychic power.

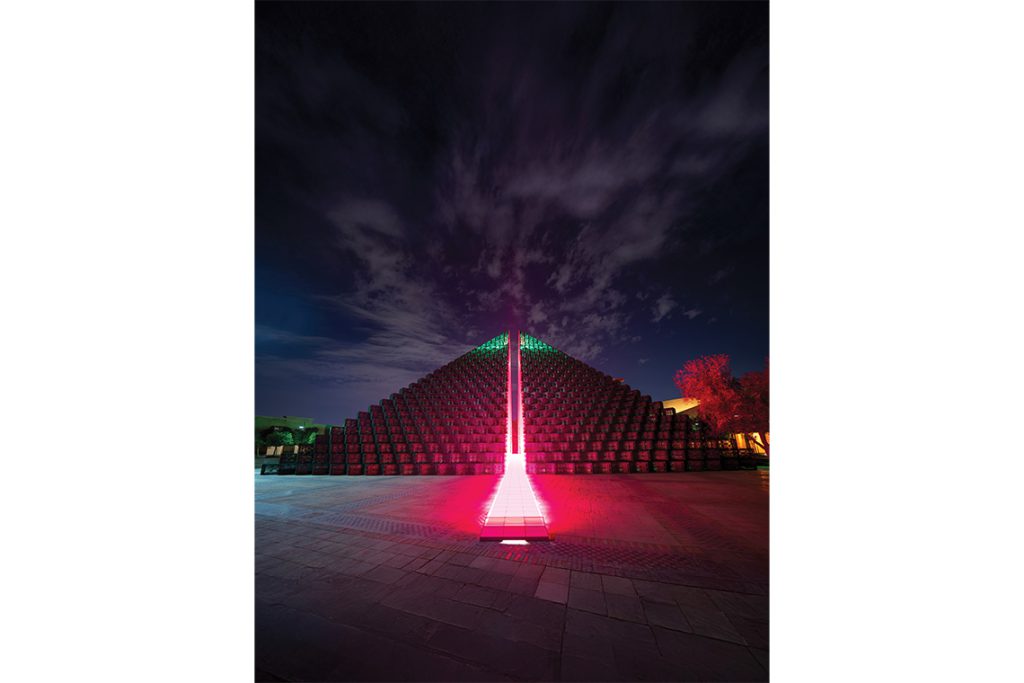

The second record was set by Rashed Al-Shashai’s The Fifth Pyramid (2024), for the Largest Illuminated Recyclable Material Sculpture of a Pyramid, a scaled-up iteration of his ongoing series that presided over a plaza in the lively King Abdulaziz Historical Center complex in downtown Riyadh. Made of metal scaffolding and plastic shipping pallets, the work speaks to the country’s metamorphosis from a petrochemical-based economy into one predicated on creativity, innovation and other buzzwords, with Riyadh at its centre.

Nearby, United Visual Artists’ Aether (2024) drone show was performed every night. Based on the Pythagorean concept of Musica Universalis, or the inaudible harmonies made by planetary motion, the performance modulated from a kind of flying carpet to a chaotic, swirling chandelier – a thuraya in a literal sense. Pure spectacle, done really well. I found it particularly pleasing that the humming of the drones was perfectly on key with the accompanying music. Also engaging was Janez Grošelj’s eerie atmospheric simulation of lightning and the apocalyptic surface of Venus, Alchemy of Atmospheres (2023), which did not gesture at climate change so much as make it visceral.

Mostly, however, there was a preponderance of smoke machines, motion sensors and projection mapping technology, which were all particularly well represented this year. Especially successful in this vein were Yann Nguema’s furrily primordial The Well of Life (2022), and Filip Roca’s generative data viz projected onto a water tank, The Stream (2024). Easy, interactive, and fun for kids and adults alike for sure, but is that all there is?

The real standout, also at Murabba, was VOUW’s Chairwave (2023), a row of mechanised chairs with a retro game show-style hotseat energy that explicitly discourages social distancing. When someone sits down, the seats next to them lights up and unfolds – you cannot sit alone – in an example of technology that brings people together rather than alienates them. When unoccupied, the chairs do an earnest little stadium-style wave. There’s something almost anthropomorphic about them, a sense of a worker gratefully getting a seat on the bus after a long day on their feet. I’ve never felt such empathy for a row of chairs before. The work feels like a rare example of thinking about what else light art can say, what it can do beyond expressing nostalgia for the past or excitement for the future, however beautifully or enjoyably it is done.

While billed as the world’s largest light art festival, this edition of Noor Riyadh was noticeably smaller and less ambitious, with 18 Saudi and 43 international artists contributing around 60 works across three hubs. The exhibition component was jettisoned too, while retaining the community programming. Compared to the sprawling 2022 edition, which featured 130 artists and nearly 200 works spread across over 40 sites, or even last year, which had more than 120 works by over 100 artists, this is very much a good thing. The result is an event that felt tighter, more cohesive and true to its core DNA: a public-centred light art festival that is, first and foremost, for the denizens of Riyadh.