An exhibition of archival and contemporary material at Goodman Gallery in London restored and revitalised the spirit of the 1969 Pan-African Festival of Algiers.

In 1962, Algeria finally won its brutal eight-year-long war of independence against France and emerged victorious to become a figurehead for African anti-colonial liberation movements. Actively exploring the new-found national identity for which it had fought so fiercely, Algeria soon became a continental hub of post-colonial expression, a premiership that was consolidated in the form of the Pan-African Festival of Algiers (PANAF) in 1969.

Bringing together artists, musicians, filmmakers, poets, activists and military leaders for two weeks, the festival demonstrated a revolutionary assertion of a modern ‘Pan-African’ solidarity, defining itself in direct apposition to European colonial powers.

The uniqueness of PANAF as an historic event has fascinated Algerian-French artist Zineb Sedira, and her recent (ended 16 March) solo show Let’s go on singing! at Goodman Gallery in London specifically investigated how Algeria’s independence as a nation also gave rise to a boom of independent arts, music and especially cinema.

“The festival was all about freedom, unity and friendship,” the artist tells Canvas. “Every African country really believed in that moment of solidarity, discovering their mutual experience of colonisation for the first time.”

Sedira specifically focused on PANAF’s position between Algeria’s golden age of cinema and the militant zeitgeist in which it thrived. Describing the cinematic productions of the 1960s, Sedira uses the terms ‘militant’, ‘anti-colonial’ and ‘third-world’ interchangeably. In this sense, ‘militant cinema’ signifies an art form opposed to Western colonial values and disinterested in the conventional narratives of Hollywood-esque productions. Sedira’s film Mise-en-scène (2019), which was shown in the gallery’s lower level, is an example of this genre. The eight-minute film splices together original 1960s film clips, taken from reels which Sedira found in an Algerian street market and edited together herself.

Commissioned by Jeu de Paume, Paris, France; IVAM, Valencia, Spain; Gulbenkian, Lisbon, Portugal; Bildmuseet, Umeå, Sweden. Image courtesy of Goodman Gallery

Having been kept without care for over 50 years, dirt and light exposure have degraded the majority of the films into abstract scars, but watching closely saw faces begin to appear from the murk. An anthology of characters was revealed before dissolving away again into the noise. It was difficult to take your eyes off it for fear of missing someone’s fleeting appearance.

In the episodes that do emerge from these films, the radicality of ‘militant’ cinema is found in the potency of the everyday – seeing people dance, families dine and individuals exist freely in simple scenes that became uncompromising statements of resistance.

Sedira adds that “Algeria was definitely looking at Italian neo-realism and French cinema verité, because a lot of militant cinema had the same aesthetic, that social way of filming people. The more socially engaged it was the better.”

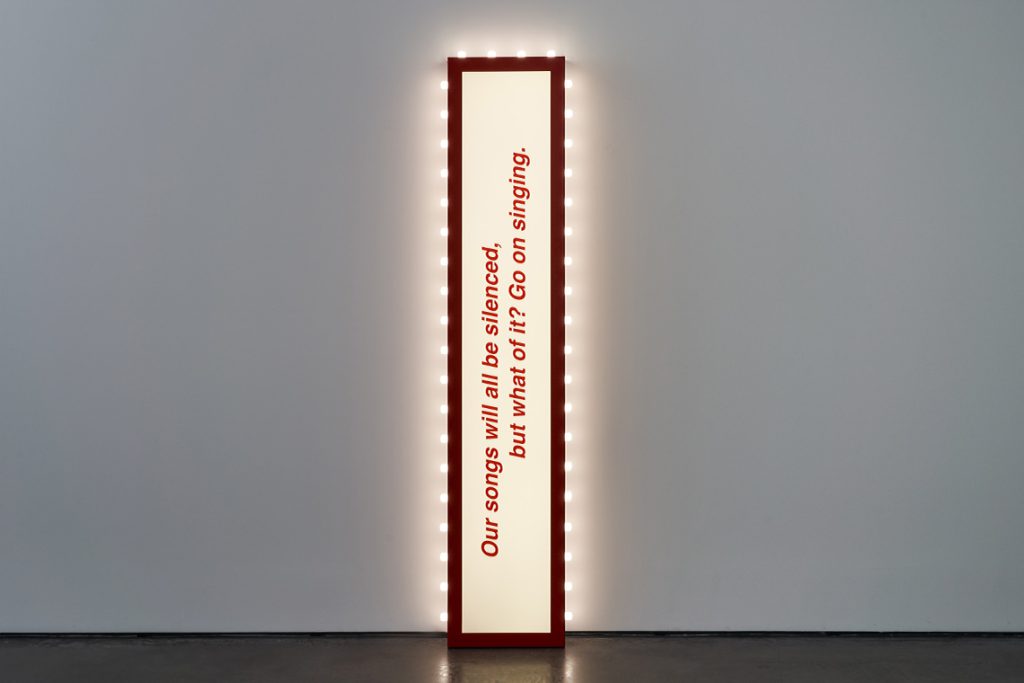

The show’s title reworked an excerpt from an Algerian state newspaper, published at the time of PANAF: “Our songs will all be silenced, but what of it? Go on singing.” Sedira commemorated a selection of these statements in a series of lightboxes; some poetic musings, some a call to arms, all conveying the strength of language used to nurture grassroots solidarity among the attendees of the festival.

Outlining the lightboxes in kitsch white bulbs, the artist mediated between the militant origin of the texts and their pseudo-Hollywood presentation, evaluating their potency when displayed in a conflicting context. As objects they bridge African and Western sensibilities, hinting that there was more of a permeable membrane of influence between the two than imagined.

“I feel the ‘third world’ loved cinema,” declares Sedira. “In Algiers they ran programmes on Japanese and Korean cinema, and were receptive to great filmmakers from Russia, Sweden and Germany. In 1965 they even presented a big programme on Buster Keaton and Charlie Chaplin, as although it was Hollywood they still agreed there were some gems in there. We have photos of Wim Wenders in Algeria in the 70s, Jean-Luc Godard came and gave talks about his films, as well as Marcello Mastroianni. It was an age of cinephiles, and we thankfully have great archives of it all.”

Archives and the preservation of knowledge occupy a vital role in Sedira’s work. Contrary to the abstract voids of Mise-en-scene – representations of all that has been irretrievably lost – Sedira’s archive-cum-artwork For A Brief Moment the World Was on Fire… and We Have Come Back (2019) filled a bright yellow gallery wall as testament to all that has been preserved but which would benefit from greater platforming.

Sedira’s access to the state archives at the Cinémathèque Algérienne, as well as those across Italy and France, gave her a means of constructing a full picture of the milieu surrounding the festival. “Not many people can go to Algeria, so I had to share my findings. I had access probably for the first and last time, and had so much information that I wanted to share, because that’s what the festival was about; showing each other what we can do and learning from it.”

The eight photomontages were surrounded by vinyl records, books and items from the artist’s personal collection, insights into the textures, sounds and filmed images experienced at the festival. “In this pamphlet you can see ‘Exposition Black Panthers’,” explained Sedira. “There is the Palestinian group Al Fatah, the anti-Zionist movement of the time. They both held exhibitions next to each other in the streets of Algiers. I got these vintage postcards from a guy on the street in Algiers. That’s Fidel Castro, Che Guevara… Ahmed Ben Balla, Yasser Arafat… Abdul Nasser. It shows how many people were being drawn to Algeria at this time.”

For a brief golden instant, representatives from the entire third-world diaspora descended on Algiers as the centre of post-colonial thought, sharing in the true meaning of intersectionality. Sedira’s research shows that one nation’s struggle against colonial powers is everyone’s.

One wonders if the gallery could have provided more information about what was on display – without Sedira’s personal guidance many crucial details and anecdotes were liked to have been missed. For A Brief Moment the Whole World Was on Fire… and We Have Come Back was an archive presented as an artwork, as it leant more into the visual tapestry on display rather than the depth of information Sedira to which has access. But in a similar way to the ‘militancy’ of the cinema of the period, the exhibition’s most radical act was often simply acknowledging the existence of those who took part in the Pan-African Festival of 1969. Remembering their voices and platforming their revolutionary actions is cause for celebration enough.