In an era when the climate crisis discourse is starting to touch every area of our lives, Way of the Forest at 421 in Abu Dhabi adds new strength to artistic contemplations on humanity’s fraught relationship with nature.

An exhibition focused on rainforests and wetlands mounted in one of Earth’s most arid regions is obviously ironic, but Way of the Forest at Abu Dhabi’s 421 is in line with the institution’s history of bringing different cultures together in some interesting ways and offering unconventional institutional support – with unexpected reach – for artists. 421 also continues to produce exhibitions that provoke conversations about art’s role in addressing global challenges like climate change and the environmental destruction caused by development agendas. Way of the Forest takes this a step further, evoking a possibly unintended but certainly uncomfortable question.

This is the second travelling edition of the Colomboscope arts festival, a major group exhibition originally presented in Colombo, Sri Lanka, to be brought to 421 Arts Campus in Abu Dhabi, following 2022’s Language is Migrant exhibition. Adapted to feature 19 artists from the Global South, including two from the Arabian Gulf region, Way of the Forest manages to highlight some similarities between deserts and forests.

Both are often held as sites of ritual and the sacred, places of mystery and deeply held tradition. Historically, both deserts and forests have offered refugees a place to regroup and think about how to improve their situation. But, while deserts are more eternal by nature, as vast open spaces where millennia-old knowledge and secrets might still be shifting across the dunes, forests can easily be destroyed and their elemental truths lost, clearing the way for new orders driven by corporate capitalism and geopolitical hegemony to take root. Way of the Forest is an exhibition mostly about pain and loss.

Curatorial text at the entrance is refreshingly absent of heady academic curator-speak, channelling instead another global art world trend toward considering nonhuman animals, acknowledging sentient landscapes and imagining more just futures. The Milk of Dreams, the 2022 Venice Biennale, for example, was a triumphal move away from anthropocentrism and a delightful envisioning of alternative cosmologies.

Here, the forest is shown to us through the relationships that humans have with it. Jayatu Chakma’s Story of the Grey Hills (2022–23) addresses development in the former home of Bangladesh’s displaced Lusai community through images of landscapes dotted with smokestacks and assaulted by bulldozers, which he has sewn onto ancestral garments.

Image courtesy of the artist

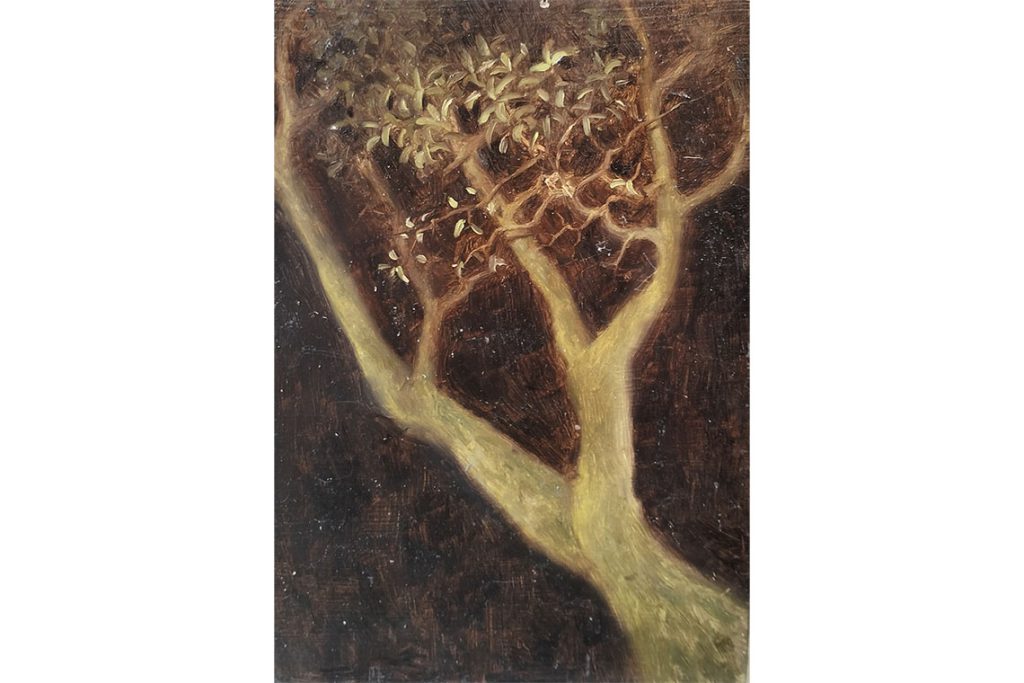

In an act of preservation and tribute, Saodat Ismailova documents the culture of her Uzbek community, which has been eroded by successive regimes. Arslanbob (2023), a video installation centered on a huge walnut forest, lovingly interweaves myths and rituals with depictions of everyday life, from a grandmother’s stories about the forest’s hallucinogenic properties to a farmer’s rhythmic cracking of walnuts with a hammer, to captivating studies of the trees’ appearance.

In one love letter to the forest itself, Karunasiri Wijesinghe draws the knots, sinuous roots and textured surfaces of trees in the Royal Botanic Gardens of Peradeniya, telling stories of both moments in the sun and the complex struggle for survival by life forms whose voices are imperceptible to humans. Quiet, elementary drawings in pen and tea stain by U Arulraj bring forth plants, animals and people affected by the ecological devastation and violence of colonial tea cultivation in Sri Lanka. In a moment of encouragement, he notes in the exhibition text that the number of tea plantations in Sri Lanka has shrunk by 171 in recent years.

Some hope for the future lies in other works in the exhibition, as well. Although Pushpakanthan Pakkiyarajah’s Hidden Mycelium in a Wounded Land II (2022–23) reflects on the charred landscapes, decomposing bodies and intergenerational trauma of civil war, it also invokes the resilience of living things through sculptures created using a process based on mycelium networks that keep forest systems alive.

Image courtesy of 421 Arts Campus

Other pieces unselfconsciously lament the loss of sacred landscapes by relating personal stories, or in Sanod Maharjan’s case, writing letters. Reviving a Kathmandu Valley tradition of handwriting notes to the spirits of the forest, Maharjan engages in a practice that is dwindling in the community as the forest itself grows smaller. Particularly poignant remarks in Letters to the Forest Spirits (2019–) address the burden of carrying the memories he writes down for the forest spirits. Like so many comments on the relentless march of global capitalism, Maharjan seems to ask what the cost of economic development is and what it would mean for humans to move away from the way we live today, to allow the forests to return to health.

The exhibition’s climax is a haunting memorial listing the names of indigenous Filipino activists killed while defending their land from the large-scale monocrop plantations, mining and logging operations plundering the Pantaron Mountain Range. Kulagu Tu Buvongan’s For Every Name a Forest (2021–23) includes a scrolling LED sign and a sound installation of indigenous elders mimicking from memory the sounds of the forest to which they cannot return.

Amar Kanwar’s The Sovereign Forest (2011–), which was also shown in Abu Dhabi a few years ago, draws similar power from a relatable fear of losing one’s homeland to oppressive forces, and like Kanwar’s gesture, Way of the Forest evokes the righteousness of defending it, as well. In addition to contemplations on how to understand the crime and what the language is that emerges to describe this disappearance, these exhibitions include works like Buvongan’s that offer a self-reflexive and potentially exhibition-defining subtext seeming to ask what we should be calling for, an audience or action?