The artist speaks to us about his efforts to reclaim Tunisia’s degraded coastal Gabès Oasis through his research-based ecological art practice.

Canvas: How did your interest in the Gabès Oasis begin?

Mohamed Amine Hamouda: I come from Gabès, spent my whole childhood here, and have been teaching here since 2013 at the Institut Supérieur des Arts et Métiers de Gabès. At first, I wasn’t aware of the cultural richness of the oasis, but with time, I became more sensitive to it. The issues facing the oasis, due to the high levels of pollution from industry, are linked to socio-economic factors and the climate crisis. I always say the problem is colonial. Gabès is a unique place, with the only maritime oasis in the world, yet the French decided to install a chemical factory here, which has negatively affected the area on multiple levels.

As an artist, it’s important to me to focus on something that is mine, something local, that resembles me. As I developed as an artist, I started thinking about art not just as a practice but also as a tool of resistance. I experimented with different styles and materials, but nothing felt right. I spent much of my childhood in a very old market called Souq El Henna, where people sell spices and artisanal crafts. I began thinking about developing a colour range of pigments with my own ingredients, and started using plants from the souq, speaking with artisans who have an incredible encyclopaedic knowledge of ancestral practices. I decided that I could also make my own paper, with a vegetal base. I found that a local mulberry bark was excellent for making paper using one of the techniques used to make Japanese washi paper and I experimented too with other local plants. I also met a man who told me that the mulberry trees were very important, as our ancestors used to weave silk using fibre produced by the silkworms that fed on the mulberry leaves. I couldn’t believe it. There is even a silk sample in the Louvre called soie de Gabès. That was when I truly realised the depth of knowledge in the oasis.

In the 1970s, the Tunisian Chemical Group built a chemical factory to treat phosphate mines. How has this contributed to the environmental degradation of the oasis?

The inhabitants of Gabès are almost all affected by this catastrophe. We have a high rate of illness, cancer and a lot of unemployment. The degradation is also in the sea, with fishermen, oasis dwellers and the oasis itself deteriorating at the surface. I can see the lifestyle changing slowly, even in the way people speak. Whereas my grandparents’ generation lived by the seasons, now we consume year-round. I believe the chemical factory caused a cultural, aesthetic and social crisis here.

Are there specific concerns you highlight in your work?

I am mostly trying to shed light on the deterioration of the natural environment here, while also showing the richness of the area. By digging into the history of the oasis, I hope to encourage people to think about the current situation. People tend to just go with the flow, although of course activists are protesting against the chemical factory. It is important for the local community to fight back against what’s happening, especially as the chemical factory is ageing and outdated, causing even more problems such as poisonings from gas leaks, as well as the other environmental damage.

How can your role as an artist help people reclaim what is theirs?

I try to find solutions with artisans and farmers. My team and I work with natural materials, taking whatever organic waste is available from the farms depending on the season, treating it and then using it to create the pieces. We use what is available to us based on the time of year. For example, we collect the unwanted pieces of palm trees thrown away by farmers after they have harvested the palm hearts. From these discarded parts, we can create works like NAR WE JOMMAR (FIRE & HEART OF PALM) (2023), which are five large woven sculptures created using materials from the oasis that would otherwise be considered useless. As a vast number of palm trees have disappeared since colonial times, it is even more important to work with what is still here.

Are all the materials you use linked to the oasis in some way?

They are, as it’s important for me to be self-sufficient. Everything we need is here. Even to create our dyes, we use what we can find. We try things like onion, pomegranate, gum Arabic, turmeric… Little treasures of the region, as well as a local know-how that is important to preserve and pass down.

What is the role played by colonisation?

The chemical factory is a colonial product. It was built to serve the interests of France, even though it was presented as something that would create employment and benefit us. The opposite has happened. We are in an economic crisis, and despite the employment opportunities created by the factory, far more people have been negatively affected by it than have benefited. As locals, we need to reject the idea that living in an industrialised society is better, by moving towards a more ecological way of being that is more natural to our past. To achieve this, we must gather our knowledge of the area and rewrite our own history with our sensitivities, our language. The documentation we have on the oasis is from the French, and although it is very detailed, it is missing the bigger picture, namely the link between the natural environment and the people who inhabit it. Through all of the projects my team and I are working on, from the Design Doha Biennial to a museum acquisition and my solo exhibition in November, we are accumulating material knowledge, which can be used by us as a resource to create our own documentation of this place.

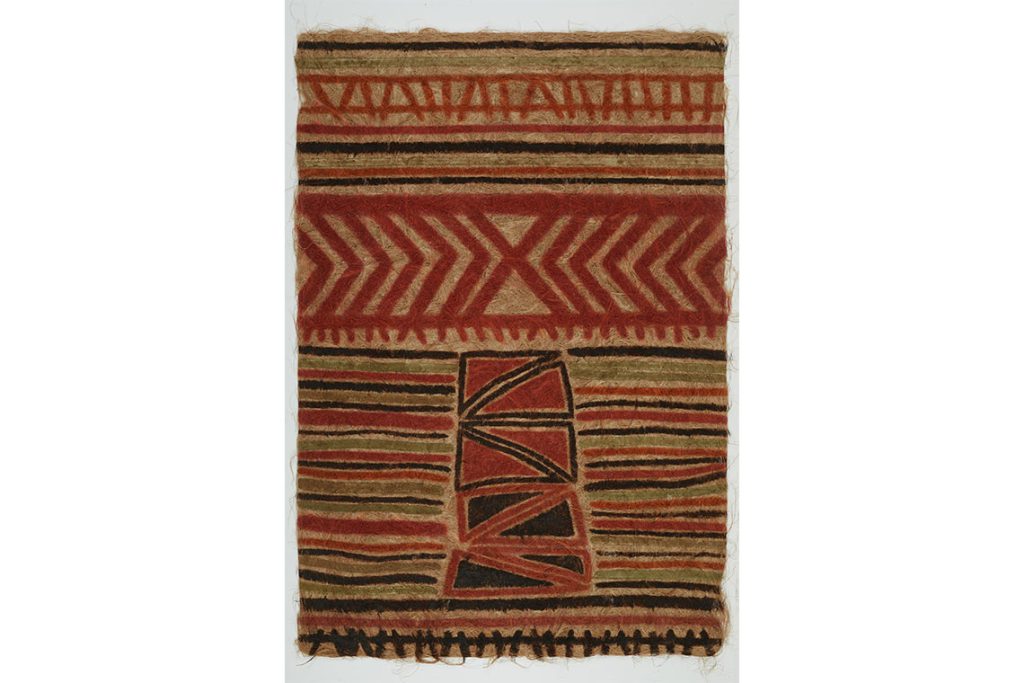

Does your series Oasis Maps (2025), which appears as geometric shapes and solid lines in various colours on textured paper, link to this reappropriation?

In this series, which proposes an aerial view of the oasis using materials gathered from it, the reappropriation is more aesthetic than anything else. Everything is made by hand, including the dyes and the weaving. Through the texture, the colours, I wanted to highlight the dryness of the oasis. I was seeking to translate the landscape of Gabès through this work, to show the paradoxical nature of it. The oasis appears as a type of paradise, but if one goes near the chemical factory, it is more like an apocalyptic hellscape.

What do you hope people take away from your work?

I am trying to share my history, which is inextricably linked to this region and to its destruction. But I live here, and future generations will too, so it is important that people are aware of the richness of Gabès, of its history, its mountains, its sea, its oasis, so that they want to live here. Everyone is trying to leave because it is so polluted and marginalised. This place doesn’t deserve that.

This interview first appeared in Canvas 120: The Traces Left