Blending allegory, bureaucracy and post-colonial critique, Freudian Typo’s solo exhibitions at the Hayward Gallery and Delfina Foundation traces how debt shapes memory and morality.

There is a cat sitting on small portable steps in the centre of London’s Hayward Gallery project space. He is called Palmerston, and he looks like he owns the place. With all the confidence and ego expected of a domestic cat, he looks up towards a large temporary digital road sign: “TRUTH AND RECONSOLIDATION” it reads, in illuminated yellow pixels. Maybe Palmerston is trying to make sense of it, or perhaps he is confused by the misspelling and trying to untangle it into meaning.

Palmerston (as you may have guessed) is not a real cat, but one made of mixed media by Freudian Typo, an Iranian-Canadian artist duo formed of Ghazaleh Avarzamani and Ali Ahadi. As Palmerston knows the artists well, he has probably already guessed that the sign’s miswording of “truth and reconciliation” – the process of healing and addressing past injustices resulting from conflict, oppression and colonialism – was a deliberate Freudian typo.

Avarzamani and Ahadi swapped ‘reconciliation’ for ‘reconsolidation’ to build new meaning into the understood phrase. A concept related to psychology and neuroscience, reconsolidation is a process by which – during therapy – a memory is reactivated into a soft, transient state which can then be reconsolidated, or restabilised, allowing for the integration of new information or emotional shifts. Potentially valuable for human therapy related to PTSD or traumatic experiences to reshape memory, it is a process mainly tested on animals – perhaps Palmerston has such experiences.

For Freudian Typo, it connects obliquely to an historic English nursery rhyme, here replicated through a photograph of an open book. In The Old Woman and Her Pig , a woman finds a sixpenny piece, then nicknamed a “tanner” after John Tanner, the chief engraver at the Royal Mint who designed the coin. The woman invested the coin in a pig from her local market, but the animal would not jump a stile on the journey home. She asked a dog to bite the pig to make it jump, but it refused; she then asked a stick to beat the dog, then fire to burn the stick, water to quench the fire and so on in an absurdist cumulative tale which turned darker until she asked a rat to gnaw a rope which would hang a butcher. “Sent by the invisible hand, a cat appeared in the woman’s sight…” – perhaps Palmerston – and made a demand to help, chasing the rat who then gnawed the rope and, eventually, the pig jumped the stile.

the Hayward Gallery

Although Freudian Typo’s Palmerston cat is not real, he represents a real cat who ‘worked’ as chief mouser at the British Foreign Office until 2020, keeping mice away from the historic governmental buildings. Named after the nineteenth-century British prime minister who oversaw colonial rule, images and objects in the display speak to other forms of colonial conflation with finance, to ideas of neoliberal laissez-faire free-marketism, and forms of collective memory and dependency fostered by institutions – a line on the wall maps the route you would follow from the Hayward Gallery to reach the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development in the City of London, represented here by a small architectural model.

For visitors who follow the cumulative tales and clues, there is a lot of meaning embedded in the items and images of this installation. It is intriguing and alluring, but only half the story – those who want to deepen their exploration of Freudian Typo’s complex amalgamation of empire, debt, animals and memory should take the walk across London where the second act of the split-venue project fills the basement galleries of the non-profit arts organisation, the Delfina Foundation. It is a route that could pass Somerset House, where colonial taxes were handled; Great Scotland Yard, the early headquarters of the police; the former War Office, where muscle to support colonial governance was organised; the Foreign Commonwealth & Development office, where the chief mouser worked; the HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC); and Buckingham Palace, the centre of the Empire.

Freudian Typo’s two exhibitions encompass the places that contain all the ingredients of their inquiry, and they also encompass two distinct modes of exhibition making. At the Delfina Foundation – where Avarzamani was a 2022 artist-in-residence – their approach is markedly different from the white-wall hang of the Hayward. Here it is immersive, the main gallery kitted out like an undetermined waiting room – perhaps a tax office, or a hospital ward, or maybe a veterinarian practice. The artists call it a “Debterinary”, and around the walls are posters and signs that riff off the aesthetic and language of governmental, corporate, financial and medical institutions. H.EM.RC (punning off HMRC) posters read “atonement filed quarterly” and “go in peace and keep your receipts”.

This is a multilayered work that does not shout out any singular meaning, but repeatedly lays down insinuation, idea and suggestion for the visitor to weave their own connections. Language, however, runs through it all. Another H.EM.RC poster lists words connected to language, spirituality, health, and restitution: Atonement, Reckoning, Redemption, Penalty, Tribute. Freudian Typo’s interest in post-coloniality is also unmistakably in the room – a scale model of the statue of Winston Churchill in Parliament Square is here, but it has been sliced vertically so the imperial former Prime Minister’s left shoulder and leg is cut off, and his engraved name is also split in two to fold in the health pun: CHURCH ILL.

Image courtesy of Delfina Foundation

The presentation at Delfina Foundation is rich and immersive, inviting the visitor to sit in the waiting room and contemplate everything that is built into the experience. It is a shame, perhaps, that most visitors who encounter Freudian Typo’s double-headed offer will only catch the Hayward presentation, which is centrally located in a gallery with heavy footfall and also hosting a popular Yoshitomo Nara exhibition. The Hayward show offers not nearly as many hooks into the underpinning world from which Freudian Typo draw, and many visitors – especially perhaps a less-gallery-going crowd who chance across it after seeing the Nara – will likely be nonplussed by the rather spare and conceptual presentation and not even understand the mis-phrase on the sign.

Those who do cross London to Delfina’s display will be rewarded with many more loose strings to intellectually tug on and a mode of display that is altogether more intriguing and inviting. One cannot help but wonder what each space would have looked like if the venues had switched around, if the Delfina hosted the traditional hang and the Hayward was turned into the immersive Debterinary, a space which surely would have enticed a regular gallery-goer into the space and ideas far more deeply than the current arrangement.

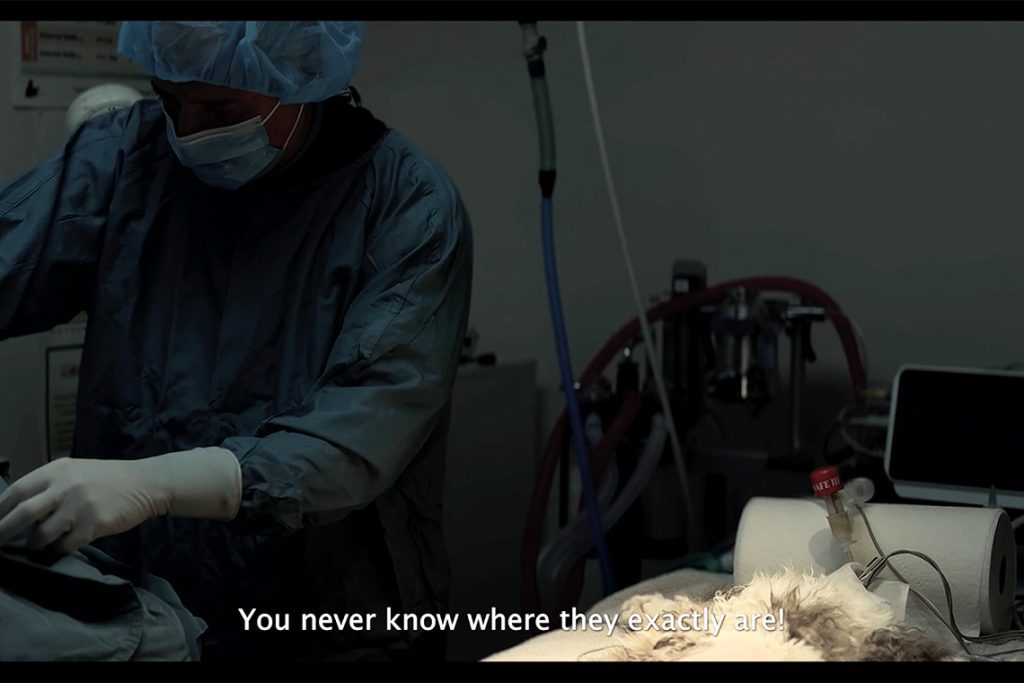

Visitors that do manage to see both spaces will be rewarded, not only with the waiting room scenography but also by a poetic connection that ties together the conceit of both galleries. A second, darkened room at the Delfina has a looping film showing a domestic cat undergoing veterinary surgery (not Palmerston, but perhaps they once met). A female voice asks “Are you sure it’s the cat that ate the coins?” and we are left wondering what kind of operation is happening here. Is this setup not to repair the cat but to archaeologically recover something of value from under its flesh? “It doesn’t matter, coins or no coins” a man replies, “in the end, they all go under the knife. After all, one has to pay one’s debt.”

A text on the wall carries the words to Chad Gadya (One Little Goat), an Aramaic song from the end of the Passover Seder that, like The Old Woman and Her Pig, is a cumulative, absurdist tale. Father bought a goat for two coins, a cat then ate the goat, a dog bit the cat, a stick beat the dog and so on through a similar flow, this time ending with the angel of death killing the butcher. The film, perhaps, shows this expensive veterinary surgery was needed to undo the chain of events to recover the original coins and value.

“He doesn’t know what it really means to be in debt,” the man says of the cat, “something that’s always tied to coercion and moral violence.” This conflation of the global political economy, rooted in historic and ongoing colonial practices, with the critical device of debt – historically a tool of colonial control and now similarly used as leverage between the rich Global North and the indebted Global South – is playfully intermingled with the poems. Read as parables by Freudian Typo, the texts speak about “the disappearance of capital and debt” within a system and how a cumulative chain of connections is then defined by and punished for its relationship to that original debt.

Ghazaleh Avarzamani and Ali Ahadi ask, if that original debt was so small, why is the violence and inequality within our late-stage and post-colonial capitalism so great? That debt is now infused through centuries of political and fiscal economies and is now the driving force of all our modern systems, from the social to the cultural to the individual. Freudian Typo do not propose answers in their anatomising artworks, but instead seek to situate us in the middle of our own absurd accumulative tale.