Winner of the latest Richard Mille Art Prize, the artist unearths and dissects myriad layers in a quest for clarity and understanding.

“My reasons for fostering an artistic practice stem from a place of protest and resistance,” explains Nabla Yahya, whose work is characterised by material experimentation and grounded in a rigorous engagement with politics and history. Born in Abu Dhabi to a Kashmiri father and a Keralite mother, she grew up between Dubai and Jeddah but always wished for greater access to museums and galleries. Art classes at high school, however, provided a valuable outlet. “I felt it was one subject where I wasn’t really thinking about myself in any sort of egotistical way,” she recalls. “I wasn’t anxious, and it also gave me a greater sense of clarity.” Yahya’s drive and precise point of view have contributed to her being named as the winner of the 2023 Richard Mille Art Prize, but her path to such recognition has not always been straightforward or direct.

Yahya decided to study architecture after her first choice of double majoring in philosophy and film was vetoed by her pragmatic parents. She got into her dream school in London, but describes the period as an “extremely dark time”. Upon arrival, she realised that the post-Second World War, pre-Thatcher era that had produced the architecture of the Barbican and the South Bank, and which she had romanticised for its socialist ideals, had given way to deeply entrenched neoliberalism. Demoralised by the industry’s complicity with labour exploitation and environmental degradation, she decided she didn’t want to practise architecture and returned home to Dubai in order to figure out her next steps.

A longtime admirer of Forensic Architecture and especially the work of Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Yahya serendipitously discovered that he had relocated to Dubai. “So I did something very out of character,” she says. “I reached out, asking if he needed an assistant, and went on to work with him for the next four years.” Not only did this time prove both inspiring and restorative for her tattered self-confidence, but it also allowed her to understand how an artist could bridge multiple disciplines, with an expanded sense of what an artwork could do or be. “It was really helpful to work with Lawrence while he conceptualised an idea and then took that concept and turned it into something tangible,” she explains. “I think the act of someone trusting you allows you to trust yourself more.” Despite not having made her own art for years, in 2019 she was invited to apply to the Sheikha Salama SEAF fellowship, an opportunity for which she remains grateful and which “allowed me to really think about this possibility of being an artist rather than that it being something that’s fantastical or unfeasible.”

Rather than take from the built or natural environment, Yahya’s works are shot through with the affective concerns of life as a resident non-citizen in the UAE: feeling politically stifled and with a sense of interminably treading water in limbo. The Pandemic Album (2020–22), a video triptych that montages footage of global immiseration, alienation, rage and collective solidarity, was drawn from both news reports and social media. Initially commissioned by Shumon Basar for the 2020 Global Art Forum, Yahya continued to document the period to present an updated and extended iteration under the curatorship of Maya El Khalil at the Portrait of a Nation II show in 2022. There is the possibility of this becoming an ongoing work, “as the pandemic never really came to an end”, but Yahya has since stopped working on it, given its heaviness. “The material was extremely painful to work with because I was engaging with so much trauma, including the struggles of doctors who felt helpless and particularly the selfishness of others who refused to accept that public health is a collective responsibility,” she says.

Of course, there are cyanotypes too. Commissioned by Murtaza Vali for Proposals for a Memorial to Partition at Jameel Arts Centre, Silsila (2022) unspools the colonial machinations that led to the brutal siege of Kashmir, which in turn underwrites Yahya’s preoccupation with dispossession and displacement. She has wanted to make work about the issue for a long time, but relates that “I’ve always felt that it’s not my place to talk about it because I have never suffered directly from any of the violence and have had the privilege of leading a very safe and secure life. There is so much weight and pressure when dealing with this subject matter that I have felt really lost and overwhelmed by the responsibility.”

In Silsila, Yahya presented a collection of artefacts connected to the historical narrative of the region, and told its recent history through images. She looks to create an ephemeral lightness of texture that belies the weightiness at the heart of the matter, remembering in particular how, as a student visiting archives in London, she would only ever be able to leave with photocopies of sources. “What moved my father when he saw Silsila at Jameel was actually setting eyes on the document of accession and realising how trivial the two pieces of paper are. They were just like a ‘fill in the blanks’ form, seemingly so insignificant but something that wrought so much violence upon these regions,” she says.

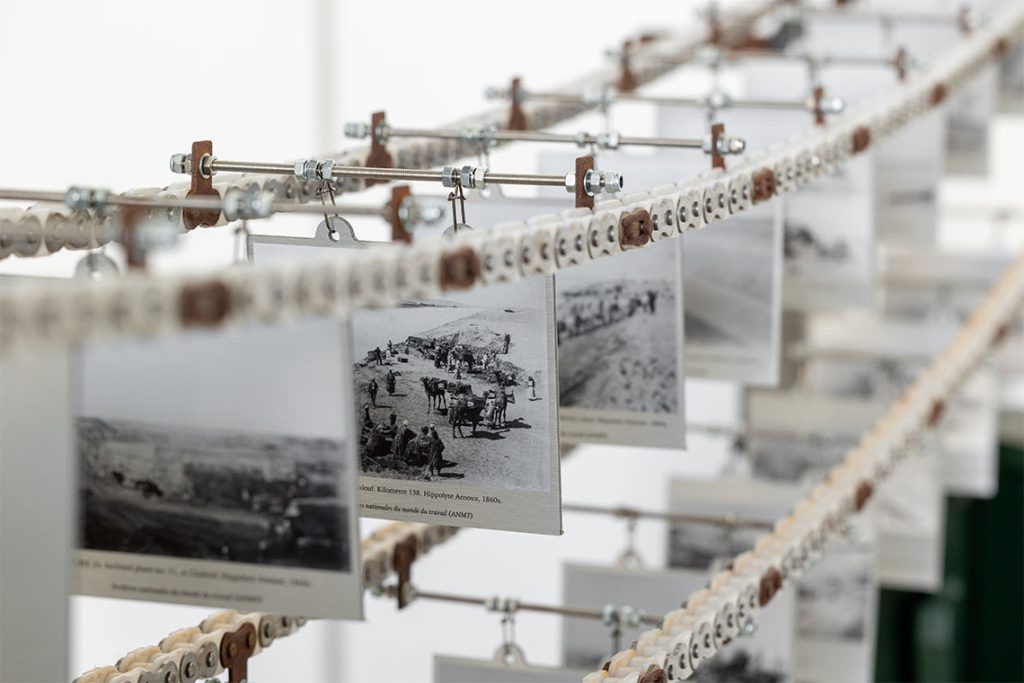

The approach Yahya used in Silsila revolved around the extensive use of digital archives, a process that she extended further in her preparation of the concept and implementation of SoftBank (2023). “I began thinking more deeply about the Suez Canal in 2021, when the container ship Ever Given became lodged in the canal, halting global trade. While I had been familiar with the history of the canal since the 1950s, I realised that I had taken its existence for granted, and so I began reading about how it came to be.” Yahya began to devise a project after learning that the canal had been created by hand under a system of forced labour and was also a product of the practice of concession, a practice which continues today through forms of neo-colonialism. “Through SoftBank, I attempted to call attention to exploitative labour practices, as well as comment on the production of soft power through the construction of colossal projects,” she explains. In SoftBank at the Louvre Abu Dhabi, for example, archival printed matter is viewed through a hand-cranked carousel which takes some effort to turn, in a reminder of all the workers whose labour built the Suez Canal and so many other flagship megaprojects like it. “By focusing on a historical precedent, one is able to elucidate the ramifications of contemporary life, bringing to light our complicity in present-day violence and injustice,” she affirms.

When in doubt, Yahya tends to return to her extensive research. When not in doubt, she does the same, often consulting with academics to further her understanding. For her winning Richard Mille Art Prize work she reached out to Dr Lucia Carminati, whose book Seeking Bread and Fortune in Port Said: Labor Migration and the Making of the Suez Canal, 1859–1906, was especially valuable. “I think it’s really helpful to seek advice from people outside of art, especially historians like Dr Carminati who mostly approach a subject from an unbiased and objective point of view, whereas an artist can be absolutely passionate and is allowed greater freedom of expression.”

Meanwhile, Yahya’s interest in the dynamics of labour led to her involvement in a collaborative work, reconstruction: Crew Rest Compartment from the archive of ‘Emirates staff No. 460956’ (2023), with her fellow artist and close friend, Mati Jhurry. Commissioned by Murtaza Vali for the exhibition Guest Relations at Jameel Arts Centre, Jhurry conducted a long durational performance as a member of Emirates Airlines cabin crew for period of three years. She wished to represent the crew rest compartments within aircrafts, in which cabin crew members are required to rest during long-haul flights. Working from spatial details she obtained from Jhurry’s memories and a single image of the compartment in an Emirates Boeing 777, Yahya began modelling a translucent, shell-like fibreglass sculpture, one that is fragmented in order to convey the hazy quality of memory, save for Jhurry’s bunk which remains whole to reflect the clarity with which she remembers her spatial experience of this space. “I am honoured to have been able to commemorate Mati’s feat of immense endurance with this work,” Yahya says.

Winning the Richard Mille Art Prize has left Yahya feeling validated, clear-eyed and even optimistic. Taking this project as the nucleus, she plans to extend her engagement with the Suez Canal to consider the developments of the 19th century as a whole. More than anything, she looks forward to finding – or forging – a community of like-minded people. “I think that’s the next step,” she affirms. “What comes after representational art is very important. I think that a growing number of people are of this view and feel kind of debilitated to change anything. So now we need to convene and discuss what we should do next.”