Things are not quite as they seem in Mohammed Sami’s current exhibition Isthmus, where the artist plays with form and representation as an invitation to look beyond the surface of the canvas.

Standing at the entrance to Isthmus, Mohammed Sami’s solo exhibition at Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin, the viewer is presented with an urban scene, gazing towards a densely packed arrangement of buildings. They look a bit modernist, perhaps mid-century concrete but with scratchy brickwork evident in places, although it is hard to read it accurately through the thick yellow fog that has enveloped the whole scene. A constellation of white artificial lighting struggles to break through a smog which also works to keep meaning at a distance from us as we look into the eerie set piece. In the foreground what at first look like wildflowers are, on closer inspection, plastic remnants and rubbish caught on overgrowth. The title, Upside Down World (2024), also doesn’t help locate us much spatially or psychologically within this unpeopled place of seeming abandonment.

It is the largest work in a tight presentation of nine paintings, all made since 2023. Born 40 years ago in Baghdad, then emigrating to Sweden aged 23 and now living in London, Sami’s geographic journey is presented. Not all the works depict architecture or place with the clarity of the opening urban view, but each lures in the viewer with a promise of representation, then breaks those expectations with new perspectives.

We are never quite sure what we are looking at with Sami’s paintings – we aren’t even certain in which direction we should be looking. There is no single focus point, the artist instead trying to pull our gaze beyond the pictorial surface and venture deeper to other places. In Emotional Pond (2023), that other place is inverted, an architecture that may be a distant cousin to the first encountered, but is upside down and contained within a small red opening in an otherwise deathly black canvas. At first this reads as a puddle in muddy ground, but as we get pulled deeper into the scene something doesn’t seem right. Perhaps – as the title suggests – we are looking downwards onto a water’s surface covered in oil, a small moment of separation revealing a reflected scene beyond.

Sami speaks of thereness being important to the ideas depicted in his works, a sudden and momentary dislocation of self into a sense of being elsewhere. This may be fuelled in several ways: from a personal migratory history; the artistic hunt for imaginary spaces; and perhaps a haunting yet distant memory of Iraq and all that has happened within it since the 1980s of Sami’s childhood.

The downwards vantage of Emotional Pond is repeated across other works. We seem to be looking down at a path in The No Return (2023), Sami’s framing serving to pull our focus from a horizon view to stop us knowing where we are heading. The ground is white, perhaps forgetful snow within which the dark tracks are not only a physical route through landscape, but also a psychological journey towards the return of memory.

In Under the Palm Trees (2023) we again have our gaze forced downwards. In what appears to be the rippled surface of more water, we see reduced reflections of what seem to be dark towers. The water is a rich red, an inferno bursting from the canvas, so that it seems Sami has forced our view away from the source and into the fire’s reflected and reversed image.

When in 1834 London’s Parliament went up in flames, J M W Turner rented a boat to view the scene from the water. When he came to paint it up, he repositioned himself on the opposite bank of the river, at a safer distance and looking across to his smudged, hazy spectre of combusting power. Under the rich, red Thames of Turner’s paintings are crowds of spectators watching the destruction. Sami seems to poetically recall this distanced view and vantage point, but here the river is edged by reeds not people. The water’s surface, however, appears to be equally as alive with flames as Turner’s scene nearly two centuries ago.

Ashfall (2023) could at first be read as an aftermath of such a fire, with the surface of the linen canvas having the appearance of charcoaled wood. But the charred blackness transforms as the viewer’s eyes descend down the tall canvas – a cluster of precarious and windswept palm trees sit somehow illuminated under what is now read not as burnt wood, but dark sky.

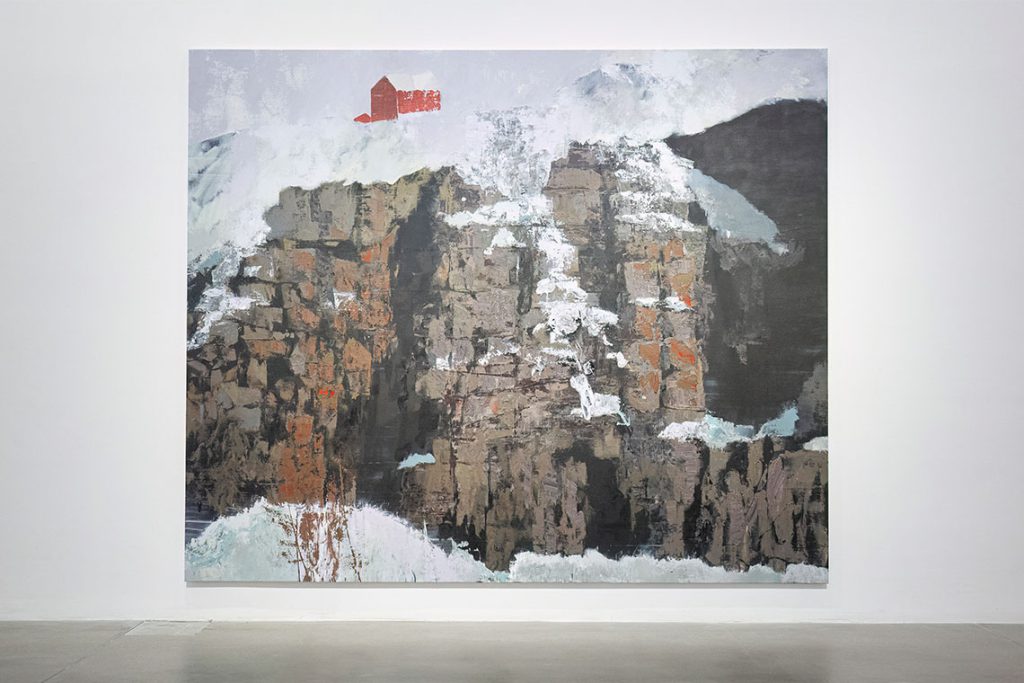

This transformation of perception recurs in other paintings. When viewed up close, a picturesque mountain scene reveals violence and anger in Sami’s forceful manipulation of the paint. In another work, what at first reads as vertical tree trunks evolves to suggest possible tank tracks. Another painting suggests white lines along a tarmac road, but under closer examination shifts to show ceiling strip lights in a dark room, offering just enough light to reveal five-line tally marks. Altogether there are a count of over 250 of them, but what they are counting and who is counting them, we don’t know.

This is a tight collection of paintings, but expansive with imbued possibilities. The title of the exhibition, Isthmus – البَرزَخ in Arabic – conjures an idea of a space existing between two others, an interstitial existence that could be physical but, seen through Sami’s eyes, is also existential and psychological. These are spaces between. Sublime spaces between, granted, but with a sinister nature implying both potential security or disaster just out of frame.

There is both longing and fear present in the paint. As Turner was drawn to the destruction of Parliament, then repositioned himself to the shoreline when submitting the memory onto canvas, so Sami also shifts location. This move keeps the viewer questioning which realm is being looked into, and also might convey a more biographical note from the artist – one of movement, memory and a conflicting desire to simultaneously both occlude and fix memory.