Bvlgari brings Serpenti Infinito to Art House at the Nita Mukesh Ambani Cultural Centre, Mumbai, in a glittering celebration of the nāga – a half-human, half-snake mythological being that occurs across myriad cultures and geographies.

Self-generated and self-reflexive, myths transmit knowledge about existence and the surrounding world. Spread through waves of human migration, they have been passed down since the Stone Age and each ‘storyteller’ – be it by flint or brush, on cave walls or paper, through oral tradition or contemporary art and design – contributes to the successive narrative. One recurring theme is the slaying of a serpentine form, found across boundless strands of mythology and which provides compelling food for thought about a shared cultural fabric and ancestral roots.

The sinuous mythological being appears in Navajo folklore in the Americas; across European legends recounting the Scandinavian epic of Beowulf, as well as the English dragon slayer, Saint George; and in North Africa, where the Egyptian god Set conquers Apep, a serpent of chaos. In Asia, Japanese lore sees Susanowo, Shinto god of the sea, kill an eight-headed serpent called Yamata no Orochi; and China has the half-snake goddess Nuwa, who defeats a black dragon to save humanity. Yet nowhere is the symbol more potent than in India’s diverse mythology, which tells of many semi-divine nāga figures, not least Hindu tales describing the battle between the deity Indra and Ahi, a serpentine demon.

Pinpointing mythological lineage is a complicated and contentious endeavour, but the wider scientific community agrees that mythical stories from separate locations and time periods bear uncanny similarities. Motifs such as the snake exist within a universal visual lexicon shared by all types of myths, denoting myriad meanings that bridge past and present, reality and the imaginary, science and mythology. In India, serpents represent fertility, freedom and cosmic energy, temptation, wisdom and transformation, with different belief systems focusing on particular dimensions. In Hinduism, Vasuki is a snake around the god Shiva’s neck, and the deity Vishnu rests upon the serpent Shesha, or Sheshnaag. In Buddhism, Buddha is protected by the snake Mucalinda, while in Jainism, the 23rd Tirthankara (‘supreme preacher’), Parshvanatha, is portrayed with a hood of snakes, symbolising his protection and detachment from chaos.

Sustained by infinite symbolic potential and relevance, snakes have also contributed significantly to the arts, where their aesthetic and biological characteristics have been appropriated, translated and continuously reimagined. The Serpenti collections of Bvlgari are an outstanding example of this enduring creative journey. Founded in Rome in 1884 by Greek silversmith Sotirio Bulgari, the luxury Italian design maison has pursued the snake since the 1940s, when it first introduced its Serpenti design. The creature’s fluidity and rich symbolic value became dynamic sustenance for Bvlgari’s innovative technical expertise, inspiring new standards of creative transformation, cross-discipline exchange and meaningful artistic expression. This heightened level of skill and craftsmanship can be seen through Bvlgari’s homage to a serpent’s overlapping scales: by studying how these facilitate smooth movement and reduce friction, the Maison was inspired to engineer its complex Tubogas technique. First introduced as a watch, the solder-free coils created a flexible band wrapping sinuously around the wrist, marking a turning point for Bvlgari’s craftsmanship.

Bvlgari’s travelling exhibition, Serpenti Infinito, embodies these diverse influences and achievements to celebrate the snake from numerous vantage points: mythology, history, craft, culture, education and technology. Held during the Year of the Snake across locations deeply connected to the creature, Serpenti Infinito launched in Seoul in early 2025 before moving to Shanghai. Now, the third iteration comes to Mumbai, where it will run during 1–17 October. Each edition features bespoke scenography housing iconic Bvlgari pieces from the Maison’s Heritage, High Jewellery and Timepiece collections, as well as material from its archives, creating a dialogue with historical objects and artworks by renowned local and international artists and institutions. Indian art gallery Nature Morte is curating the collaborative vision of Bvlgari with the exhibition’s artistic director, Sean Anderson, manifesting an immersive three-part discourse that reinforces shared cultural heritage as much as it refreshes aesthetic and creative perspectives. “India is not just a country, it is a civilisation whose roots stretch back to the Indus Valley,” says Nature Morte co-director Aparajita Jain. “Even in Harappan seals, serpents appear as powerful symbols, suggesting that the relationship between humans and snakes is among the most ancient in our cultural memory. Over millennia, the icon has occupied multiple roles: an object of fear and caution, a guardian of thresholds and, in spiritual practice, a source of inner power.”

Showcasing Serpenti Infinito in Mumbai is an important element in Bvlgari’s ethos of championing wider cultural connections, including with India. The visionary craftsmanship and design that characterises the Maison reflects a relationship forged with that country’s rich history, traditions and masterful artisanship. In antiquity, India sent gems of great quality and value to Rome along maritime and overland corridors of trade, with Italian merchants and craftsmen using the highly sought-after jewels to create the finest pieces for their clients. The relationship continued across the ages in different forms and refinements, including the twentieth-century development by Bvlgari of the Indian lapidary tradition for cabochon cuts, which celebrate volume, surface and luminance.

The Mumbai edition of Serpenti Infinito presents three exhibition chapters that delve into the South Asian perspective of the nāga, a symbol depicted for millennia through oral legends, paper works, friezes in rock-cut temples and painted village shrines. Investigating the philosophical and formal qualities of the snake helps contextualise Bvlgari’s creative interpretation while simultaneously supporting the phenomenon of shared mythologies and human connectivities.

Enveloped by deep green walls, ‘Crafting Serpents in History’ marks the start of the journey. The symbolic focus is on auspiciousness and the snake as a divine messenger and awakener of human potential; the curation complements this by emphasising how materiality and form can represent the mythological and spiritual connection between nāgas and humans. Historical objects such as bronzes, paintings and tapestries are displayed alongside blackened steel and gold bead-mounted pieces from the Bvlgari’s Serpenti Heritage collection from the 1950s–80s. Jewellery proves an especially synergetic demonstration, with Serpenti designs moving in harmony with the body.

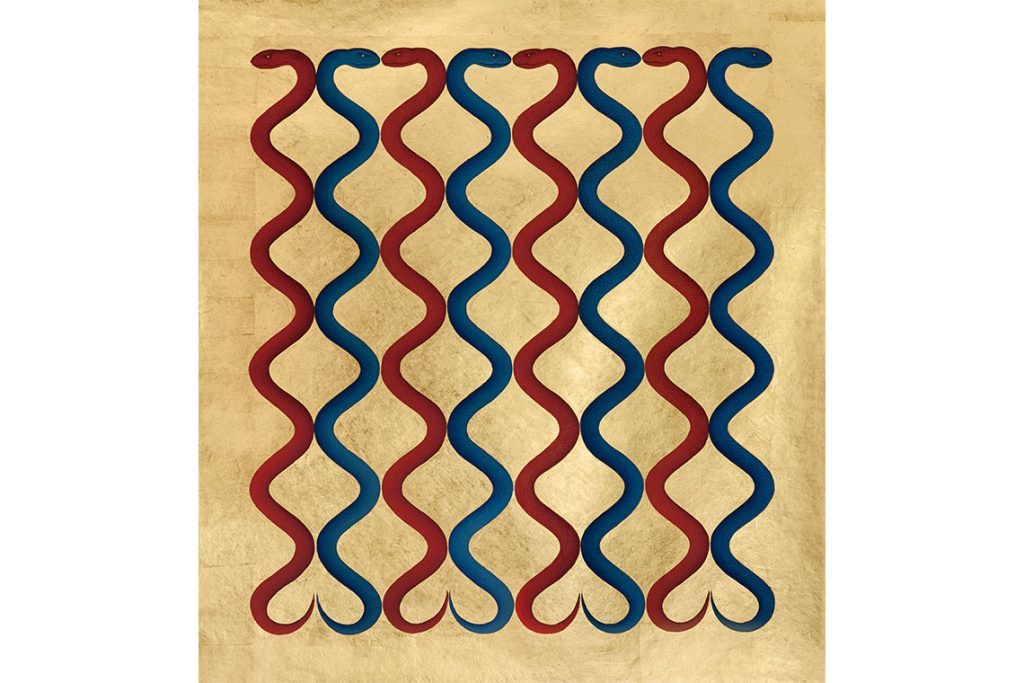

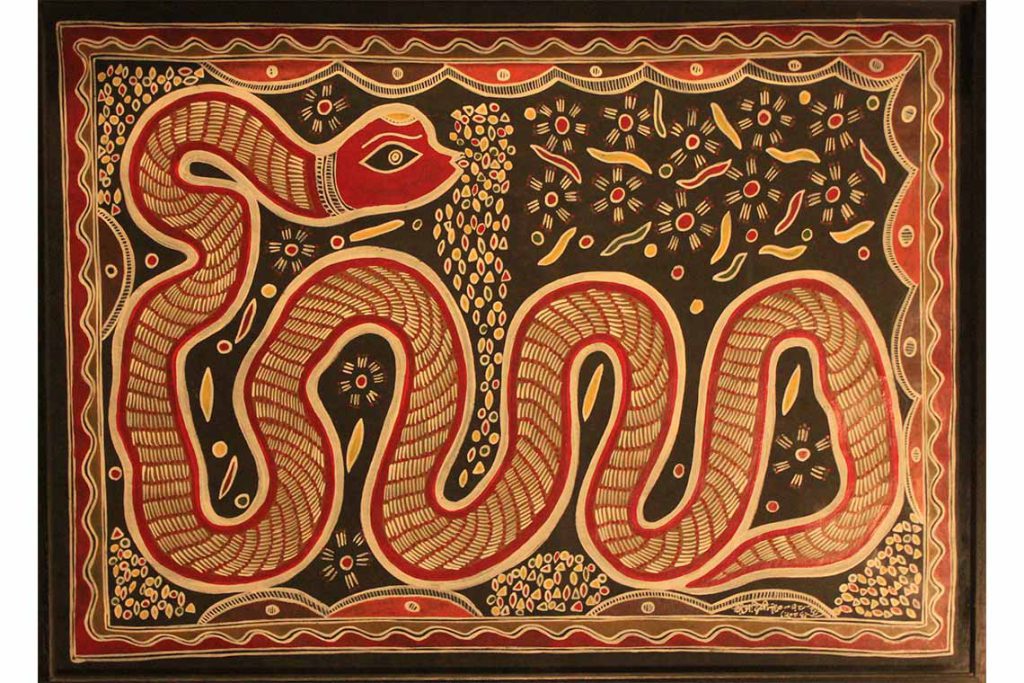

The second chapter, ‘A Mythic Presence’, conjures notions of wisdom and protection, nodding to the safeguarding role played by the nāga in the sphere of knowledge and its facilitation of enlightenment. Visitors are invited to consider dynamic narrative interplay, communal identity through time and, in the words of the exhibition text, the role of the snake as a “harbinger of continuities”. The Serpenti collection presents the distinct Tubogas, Pallini and Viper designs with a selection of modern and contemporary artworks. This approach spans all chapters of the exhibition, throughout which paper, painting, textile and sculptural works by leading Indian and South Asian artists reveal the renewable potential of nāgas. Artists include Amit Dombhare, with his acrylic and dung on cloth artwork Sheshnaag, award-winning Mithila folk artist Baua Devi, with her 2005 acrylic painting Bal Basant, and Rithika Merchant’s Gates of Horn and Ivory (2020), which delves into the crossroad between dreams and reality.

Both artists exemplify the essence of Serpenti Infinito through practices that respect the past while forming new contexts. Dombhare, informed by his Adiwasi Warli roots, elegantly merges modernity and technology into folk art tradition through the use of exceptionally fine brushstrokes – a technique passed down from his grandfather. Warli art, originally expressed in intricate wall paintings as part of ceremonial rites and as a tool of communication, often depicts mythological tales intertwined with Warli belief systems. Dombhare draws upon this foundation for Sheshnaag, which depicts a stylised semi-coiled serpent named Sheshnaag holding up the world to represent eternity, infinity and cosmic support.

With a body of work ranging from paper to murals and continuing to pass on her artistic and cultural knowledge, Devi is a pioneering artist who also learnt traditional methods from her elders. Bal Basant is an earth-toned composition dominated by two curled snakes snout-to-snout atop a floral background and enclosed by an undulating painted frame. The work interprets Mithila folk art, characterised by mythological retellings and complex geometric and linear patterns traditionally created for a home’s innermost quarters. The two nāgas indicate the cosmic balance of creation and destruction, fertility and spiritual knowledge, alongside the symphony between nature, humanity and the divine.

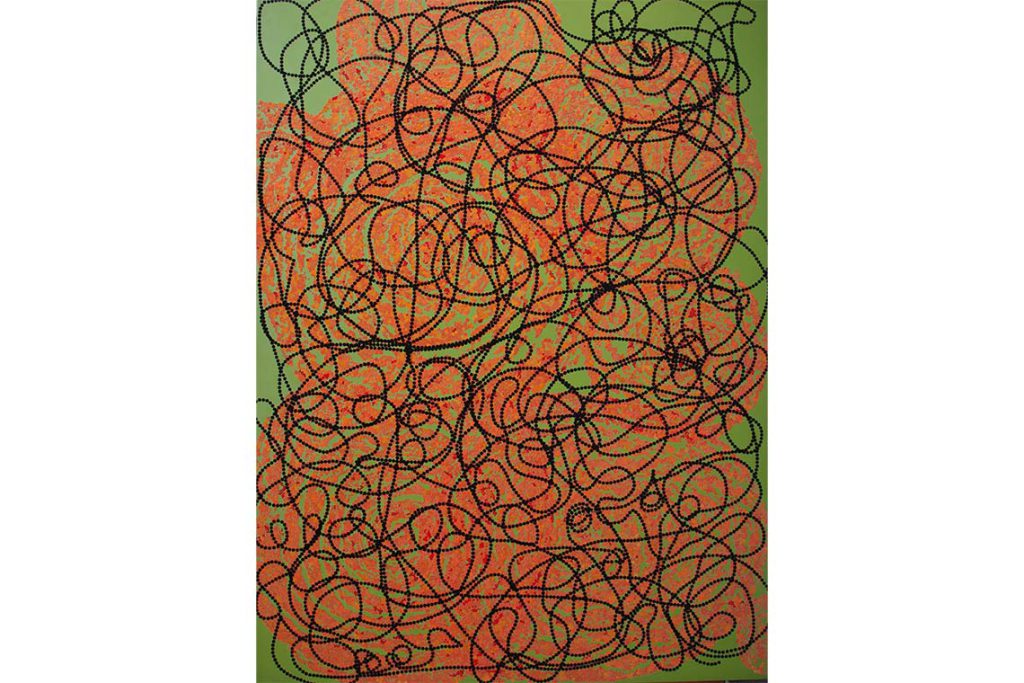

‘Infinite Transformation’ marks the exhibition’s final chapter, touching on the ability of the snake to shed its skin, both literally and metaphorically, thereby serving as a beacon of infinite spiritual and aesthetic potential. The wall text explains how “For India, the nāga embodies energy, of desire, of a people’s call to action, a safeguard, an emblem of divine hope while also transgressing the virtual and real, the imagined and built.” Visitors are able to witness how Bvlgari and artists join together to cross disciplines: the Maison’s High Jewellery collection reimagines infinity as the Tubogas dialogues with the Möbius strip and gemstones mirror serpentine shapes. Sculptor LN Tallur brings Python – Machine Learning, a bronze work made with AI and 3D printing that illustrates his take on the decorative kolam or muggu, geometric ‘welcoming’ compositions created near entrances, while AI artist Harshit Agrawal shows Untitled, revealing what he calls the “human-machine creativity continuum”. Multimedia duo Pors and Rao’s Breathing Horizon comprises a machine engineered to induce people’s subconscious behaviour and involuntary reactions while also contemplating the reciprocal relationship with the world and objects around them; meanwhile, Subodh Gupta’s bronze and brass utensil-built Infinite Sleeper references the nāga Ananta Shesha, a thousand-head guardian of sacred spaces who is both protector and progenitor, further touching on the continuous circularity of myths.

The snake’s enduring presence as a cornerstone of global mythology underscores the impact of myths on collective consciousness and creative expression, and ultimately, the transmittance of knowledge. It is through this symbol that Serpenti Infinito cements its resonance into the future. Bvlgari brings together beautiful objects, pioneering design and craftsmanship with generation-blending artworks to strengthen an ever-relevant interconnected cultural fabric. If a story, motif or object bears the responsibility of conveying a sense of meaning, then an exhibition holds the weight of supporting artistry and the knowledge from which it springs, ensuring the survival of myths for yet another generation to build upon.

Serpenti Infinito runs until 17 October