Ali Eyal’s New York exhibition alchemises the odd parallel between dreams and memories in his increasingly familiar visual lexicon.

The kinship between dreams and memories manifests itself more profoundly for some than for others. Call them daydreamers, mystics or those with a third eye. Mercurial and even wet, the thin distinction between the experienced and the mused inhabits some of us more insistently, haunting at times and caressing at others. Ali Eyal’s paintings and drawings on view at his François Ghebaly exhibition, Imagine, all this happened just an hour ago, hold a candle light to the artist’s entangled dreams and memories, melting them together thickly like a resistant wax.

At the gallery’s intimate downtown Manhattan space, a few paintings and a generous bunch of pencil and ink drawings recall film stills rendered by a masterful cinematographer. Brimming with a multitude of perspectives on an instant, they defy singular shots of a moment, not unlike either a dream or a memory. Both instantaneous and forever, the Iraqi artist’s recollections and fantasies gush with a very particular feeling of diasporic ambiguity. Inconceivably miles away from home but immediately there with a particle of reminiscence, the sense of an ever-incomplete belonging casts its obscure chimera. Just a grab away, a wholeness always melts away. Eyal’s visual notes embody this fluidity of feelings with his shaky command of figures and things. Comical at times, he depicts sinister-looking subjects who could either be a friend or a foe. Not unlike Philip Guston’s pink-washed grotesque orchestration of the political and its bleeding into the everyday, Eyal commits to a dedicated colour palette – shades of earthy tan in his case – and chunky figures in painfully familiar insanities.

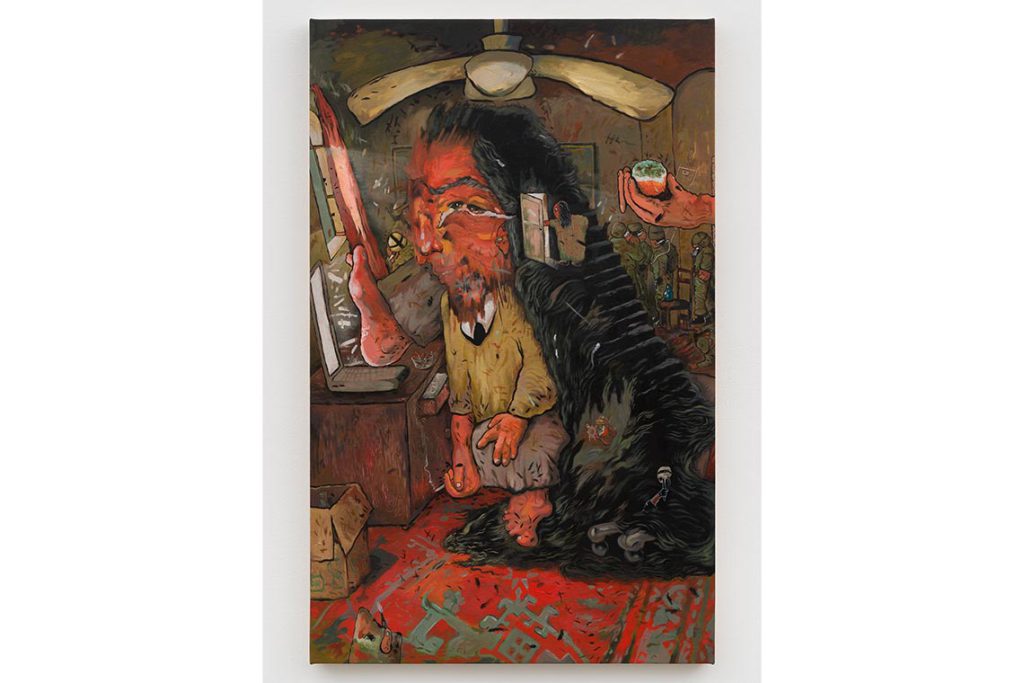

Eyal’s subjects hide a bunch in their forest-thick hairs and bodies, which they carry cautiously, comparable to a seasoned boxer or a ballerina.The painting Could you please paint this? (2025) casts the corner of a room, maybe an attic, bombarded by abrupt house objects that surround a central figure. Their eyes melt into one another and a thick unibrow bleeds into their massive curly hair. Eyal has kept a door ajar, which seems to tempt another figure to step inside. Soldiers in the back corner, and a hand offering a rotten fruit, are only two of a plethora of visual tones woven into the artist’s vignette. Like a dream, the moment seems to last forever, yet fails to deliver its cues when striven to be recollected later on. Like a cross-continental plane ride spent almost entirely asleep, the peculiar sense of arrival resonates with an unintentional immediacy.

The safe arms of memories, however, throw Eyal to perilous places: dark rooms with monstrous clutter, vehicles slicing through the skies and the roads like furious beasts, and figures with oozing limbs in dire need of stability. Another painting, entitled The road to an unknown hand (2024), possesses a whirlwind layer of incidents centring an ancient land. A car drives into a spiral of chaos, ushered along by a head with impossibly long, lush hair. The vortex rises from an elongated body, whose disproportionate head side-eyes the other head within the nexus. The earthy soil and the sapphire-hued sky bleed into one another, while a dark plane pierces through the thick air like a hungry eagle. Nothing makes sense while all roars with an internal logic – its echo convinces us to a delirious imagination.

The territories in which the Los Angeles-based artist meanders are gnarly and grotesque – all consistent in his determined visual lexicon, in which he illustrates dark interiors and open fields with a cinematic grandiosity that he utilises in the service of bizarre mise-en-scènes. Eyal’s brushstrokes reaffirm the need for painting in 2026, exploding with an outlandish specificity in his unpredictable universe. Regimented in the artist’s liquid conduction of figures and places, the works blow another suggestion of remembering against the waning of a bygone flicker. Arrestingly real and exuberantly fantasised, Eyal’s juxtapositions defy the horrors of war and displacement with sometimes equally horrific remnants of a bad dream.

The artist’s migration from his war-torn home casts its ghosts in autobiographical accents – such as the car motif, which perhaps alludes to the vehicle owned by Eyal’s father who disappeared during the war – as well as everyday objects that assume an alarming normalcy within his juxtapositions. The ordinary perhaps comes to life in the show most gruesomely in two pieces of bread thrown onto the gallery floor. Dots scribbled like breadcrumbs that homesick children in search of home trace in tales connect them. Here rock-stale bread chunks feel like they fell from the paintings, hard in their touch and foul in their aftertaste.

Imagine, all this happened just an hour ago, runs until 31 January