The artist captures fleeting moments through paintings of domestic and interior spaces that create time capsules for open interpretation.

Canvas: Your work often reconstructs moments from everyday life. How do the ideas of home and domestic interiors influence the kinds of memories that you choose to preserve?

Sultan Al Remeithi: I was born in Abu Dhabi and moved to the UK at the age of 11 for school. When I moved back fully at 26, I found myself rediscovering all the places my parents used to take me to. I would call friends saying “Did you know this spot is still open? We should go back.” I spent a couple of months revisiting restaurants, eating there again and taking lots of photos to share with everyone, showing how little had changed. I began painting some of these places, like a Chinese restaurant on Hamdan Street, just to see how it went. Over time, it developed into a series.

Many of your paintings – such as A Quiet Night Out (2023) – function as time capsules. What does it mean for you to freeze fleeting interactions of emotion?

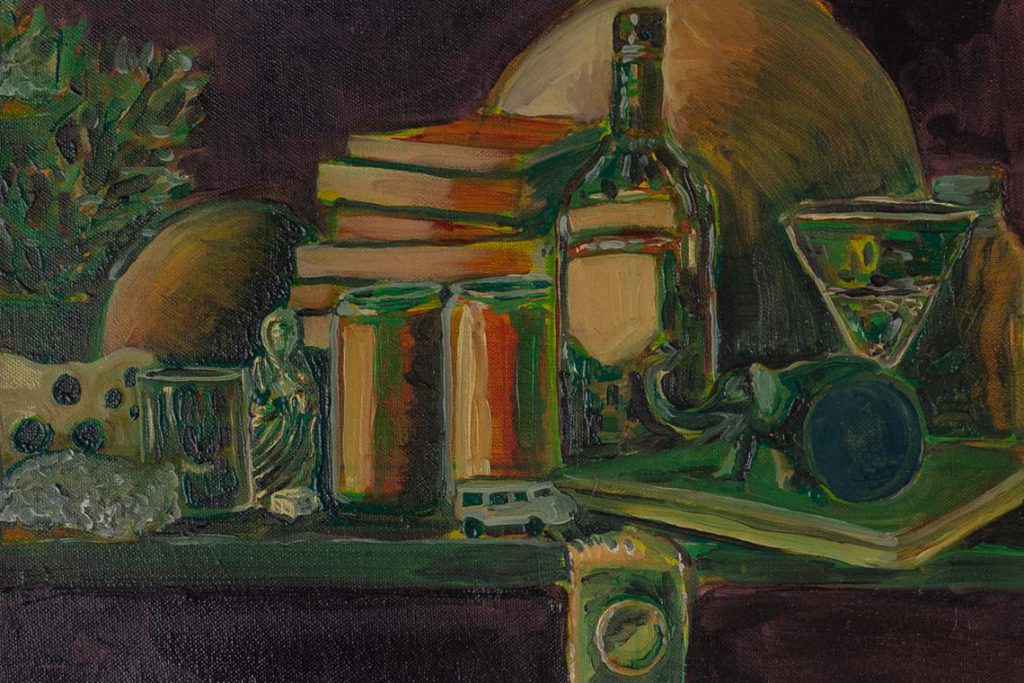

I like to leave the interpretation to the viewer. Many of my paintings are very personal – for example, A Quiet Night Out (2023) captures memories of good times at places I loved. Interestingly, it resonated with others too because there was only a handful of restaurants that everyone frequented for birthdays, graduations or special events. I enjoy seeing how others interpret a place. They might love it or have a negative experience, but I prefer not to define it.

Do you see colour as a storyteller in your work?

I’ve always loved bright and bold colours – the kind you see in a fruit market, where reds, yellows and all those natural tones just burst out at you. During university, we were often limited to two colours, which I found restrictive. I also enjoy a certain aesthetic, like old films with a yellowish haze or vintage Western colours – it sets the mood and adds a layer of narrative. I enjoy working with unexpected colours that ‘should not’ be there, just to make something stand out and feel slightly offbeat in a deliberate way.

How do your interior scenes relate to your broader interest in documenting moments that no longer exist?

I have always been interested in places that have history behind them, imagining what they would have been like in their heydays. For example, when I travel and walk down a street with old buildings, I imagine what kind of people lived there and what scenarios have taken place.

How do you decide what to include and what to leave unseen in your paintings?

Many of my works come from happy accidents. I usually start with a bunch of sketches, then slowly figure out where things need to be. It is intuitive – some works take months with small adjustments, other come together in a couple of hours. I don’t stage or manipulate the scene, I work from a photograph and, if it inspires me, I paint it.

In Sundays are not a man’s bestfriend, kiki is… (2023), the dog sits upright and alert while the figure rests deeply. Can you elaborate on what that specific moment meant to you?

At that time, I was looking through a book on paintings and came across a work by Briton Rivière entitled Requiescat (1888), it was an image of a dead knight dressed in his armour and lying on a bed with a dog sitting beside him. That composition struck me, so I asked my brother to grab the camera while I lay on the sofa with my dog beside me, trying to recreate the pose referencing a painting. I did not want it to feel as heavy or sombre as the original. That is where the greens come in – something lighter and softer. It also reflects the classic Sunday feeling after a heavy Saturday night out, when all you want to do is lie around, watch a movie, eat and just chill.

What influences the choice of objects in your paintings?

I teach painting, so I’m often building still-life setups for my students, and those arrangements usually become the starting point for my own work. I like looking at how masters approached still life, but make it my own by incorporating personal objects. Most people do not have hanging pheasants, skulls or rotting fruit lying around, but you can create something interesting and oddly personal using whatever you have.

When you begin painting a piece, how do you decide what materials, references and techniques to use?

Before I signed with Aisha Alabbar gallery, I would make collages whenever I couldn’t think of anything to paint. I would just cut out things, stick them together and not put too much thought into it. If it worked, it worked. If not, it didn’t matter. From those collages, I would pick one composition and turn it into a painting, and I still do that now. I take elements from different places and put them into a new scenario. I’m trying to do more of that, but I still enjoy finding photographs to paint from. Those pieces require a different kind of thought process – they make me slow down and be more deliberate. Some things I can paint while switching off completely, while others require a lot more thought.

This interview first appeared in Canvas 121: If Walls Could Talk