Fathi Hassan tackles issues around displacement, identity and belonging in his solo show, I can see you smiling Fatma (ended 25 May), at Richard Saltoun in London.

“Nomadism comes from oblivion. That void – which, in my life, was due to my ancestors’ displacement – has always accompanied my thoughts,” says artist Fathi Hassan. I can see you smiling Fatma, Hassan’s first exhibition at London’s Richard Saltoun and marking his representation by the gallery, delves into that void, exploring themes of migration, diasporic identity, memory and loss. Via a characteristically large range of materials, spanning collage, acrylic paint, pencil, glitter and gold leaf, Hassan draws visitors off Mayfair’s Dover Street and into a world that is simultaneously melancholy and hopeful, surreal and rooted in history, universal and deeply personal.

Hassan was born in 1957 in Cairo, to Nubian and Egyptian parents. The displacement of his ancestors from Nubia upon the construction of the Aswan High Dam in 1952, and the consequent loss of much of their homeland to the waters of Lake Nasser, has been a profound driver in his artistic expression. Building on exploration in past shows, I can see you smiling Fatma furthers Hassan’s excavation – and interrogation – of his Nubian heritage and its place in the wider world.

Image courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery, London and Rome

References to Hassan’s heritage and events in Nubian history are perhaps most overt in his twin mixed-media works, Toshk and Aswan (2012), whose title refers to both Aswan and the Toshka Lakes, created by periodic overflow from Lake Nasser; and icon-reminiscent Terhaqa (2023), which evokes the Nubian king who resisted Assyrian rule. The use of gold leaf in these works points to Nubia, known for its rich supplies of the precious metal and whose very name is thought to be derived from nub, the ancient Egyptian word for gold. Beyond these references, Nubian visual motifs – often presented in hieroglyphic style – preponderate in the backgrounds of most works. There are boats, earthenware and the faces of Nubian warriors, together with elements of the natural world such as scarab beetles, ibex and the Moon.

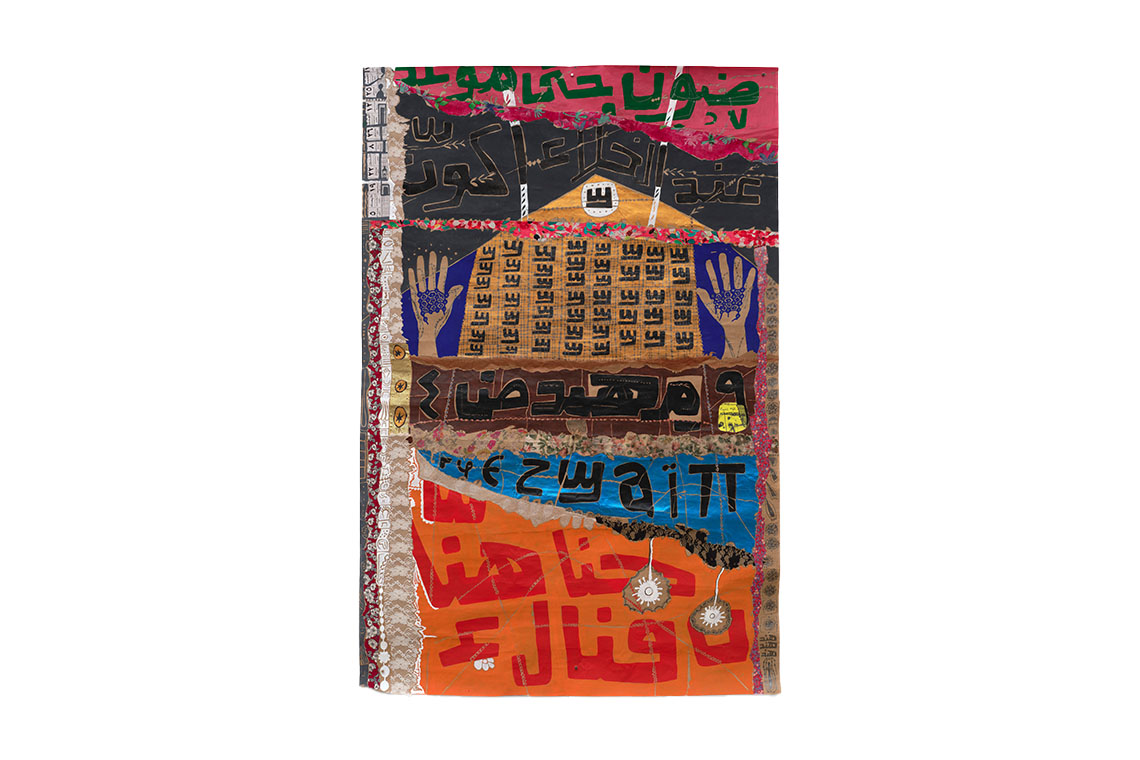

Alongside, in tension with these visual motifs and sometimes appearing to be almost fighting for space in the works, are unintelligible inscriptions. In his exposition of a multi-layered identity, Hassan challenges the role of language in fixed notions of heritage. Although based on Kufic calligraphy, the scripts are enigmatic and indecipherable, both a nod to ancient languages erased by processes of Arabisation, and destabilising the link between language as a signifier and an assumed signified. Instead, text is to be experienced as a graphic form. “I think there is no use in reading a painting,” Hassan tells Canvas. “It’s better to read a book. That’s why my painting writing is […] like water waves that cannot be counted.”

The artist’s enigmatic inscriptions are perhaps most striking in the site-specific commission that spans a whole wall at the back of the gallery. The chaotic painting is made up entirely of calligraphic script, with the paint running down from the lettering and adding an immediate sense of disarray, dynamism and the slipperiness of language – something which cannot be held still. Such an eschewing of fixed meaning is echoed visually throughout the exhibition – not least in the unreadable expressions on the faces of Hassan’s human subjects, and his use of collage in Beyond the Garden (2023) and Different Horizons…..one sky (2022), which brings an extra layer of fragmentation to the inscrutable script.

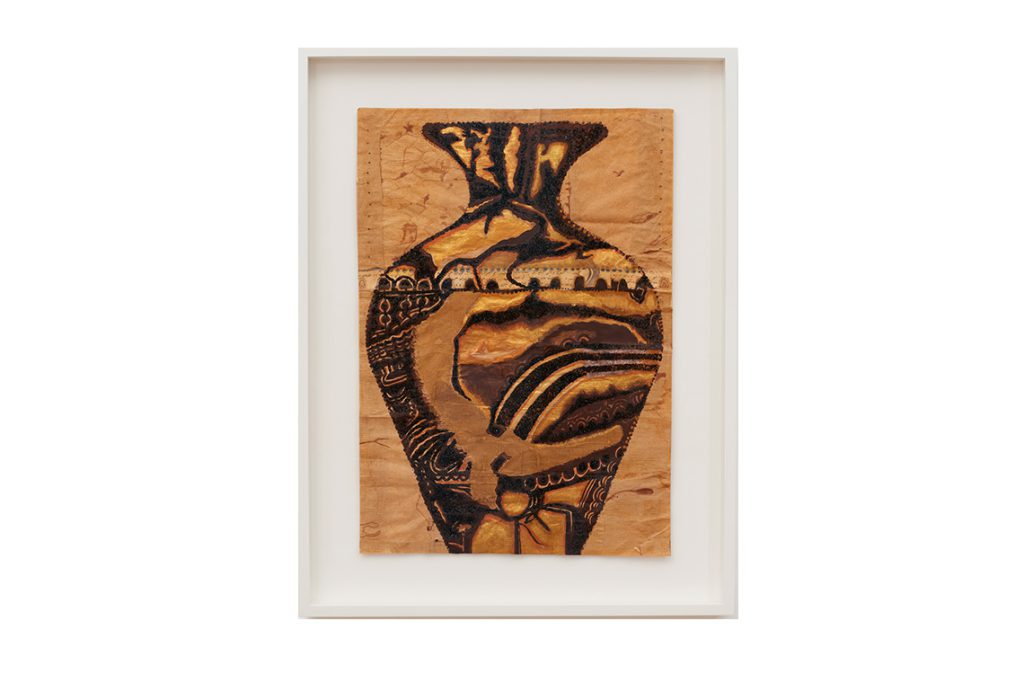

More layers appear in Secret Container (2013), where acrylic and glitter overlay what appear to be older pencil drawings, with some of these incorporated into the new image. The work takes on the form of a palimpsest, suggesting the possibility of superimposing histories, with new ones being created while still bearing witness to the old – an idea that also finds expression in the juxtaposition of Nubian iconography with traces of modernity, such as aeroplanes, that serve to link the past and present.

Image courtesy of Richard Saltoun Gallery, London and Rome. © the Artist

Beyond the visual iconography drawn from his Nubian heritage, Hassan marks this exhibition as profoundly personal in its title – the show is dedicated to his mother, Fatma. “She is observing my artistic path from above,” he says, noting that the choice to honour his mother in this show was partly because Richard Saltoun Gallery “has long been recognised for its research towards revolutionary female artists”.

The “void” born of his ancestors’ displacement – including that of his own mother – could only partly be remedied by “historical answers”, Hassan explains. In the end, he says, “art manages to absorb those questions and the discomfort that they bring.” While dealing with the trauma of displacement, his works retain an ambivalence and open-endedness, evoking the past while contemplating possible futures and potentialities. These, according to Hassan, have every chance of being positive: “Fatma […] smiles serenely and happily because her son is on the right path,” he says.

The themes explored in the show will be further examined in the exhibition Fathi Hassan: Shifting Sands, at No.9 Cork Street from 31 May–15 June 2024, which will see Hassan display works created in response to items from The Sunderland Collection.