In Sambadio at Efie Gallery in Dubai, Abdoulaye Konaté marries the rich textile traditions of West Africa and the Middle East to create a powerful visual dialogue and a striking testament to endurance.

“Ali Farka Touré’s song Sambadio is legendary,” Abdoulaye Konaté tells me. The final track on Le Jeune Chansonnier du Mali, the 1976 album by Malian musician Ali Farka Touré, Sambadio is an ode to the earth, and a call to reconcile with it. It is also the title of – and serves as a frame for – Konaté’s solo show at Dubai’s Efie Gallery.

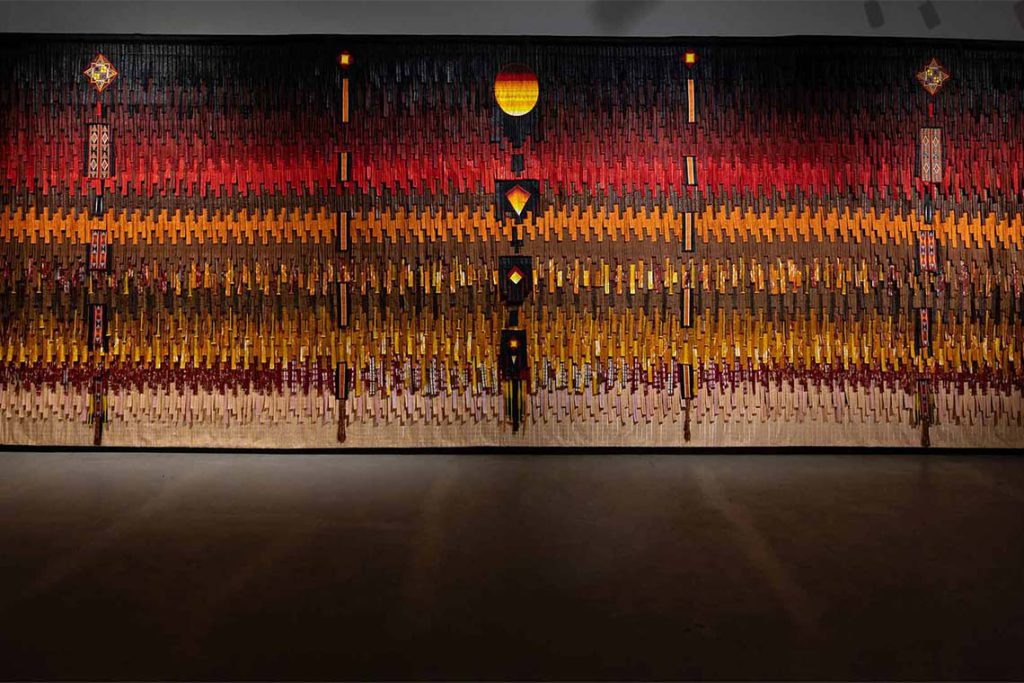

“In Ali Farka’s region in the Sahel, working the land is especially difficult and often the results are minimal,” explains Konaté, who also hails from Mali. “Only those who are persistent and determined can endure”. As such, he says, the song also reflects “a universal message of resilience and dedication” – values that are clearly dear to the artist, and which run as immaterial narrative threads throughout the exhibition, beneath the surface of the physical threads that make up Konaté’s large-scale textile-based installations. Nowhere is this more apparent than on entering the exhibition, when you are greeted by a monumental nine-metre-long textile tableau. It is particularly reflective of the titular song, as an artistic testament to the enduring motivation and determination needed to create such a large-scale work. All by hand, I should add.

It’s perhaps worth pointing out here that the entire show is made up of only five works, not including the samples from Konaté’s studio that can be found in the stairwell, on the way up to Efie Gallery’s record collection and library. Although none surpass in size the aforementioned colossal Source de lumière (Soleil) Motif d’Arabie sur Fond Ocre (2024), all employ the same painstaking technique. At first glance, Konaté’s works look like epic wall tapestries, but on closer inspection they consist of layered, woven and dyed cotton strips. He is referencing the West African tradition of using textiles as a means of communication which, he explains, includes “communicating messages for major life events such as engagements, weddings and the birth of a child”, with the patterns and designs “rich with symbolism”.

Image courtesy of Efie Gallery and Moz Photography

Engaging with this tradition, and using materials from Mali, is at the heart of Konaté’s textile art but, as writer Simon Njami – who has contributed to a catalogue accompanying the exhibition, along with Ousseynou Wade and Professor Yacouba Konaté – puts it, “tradition is made to be revised and revitalised”. As in previous works, such as his 2020 Symphonie au Kente, which brought together the textile traditions of Ghana and Mali, in Sambadio the artist marries diverse cultural references. In particular, he draws on the profound connections between the traditions of West Africa and the Middle East, as well as those of the wider Arab world, most notably Bedouin culture.

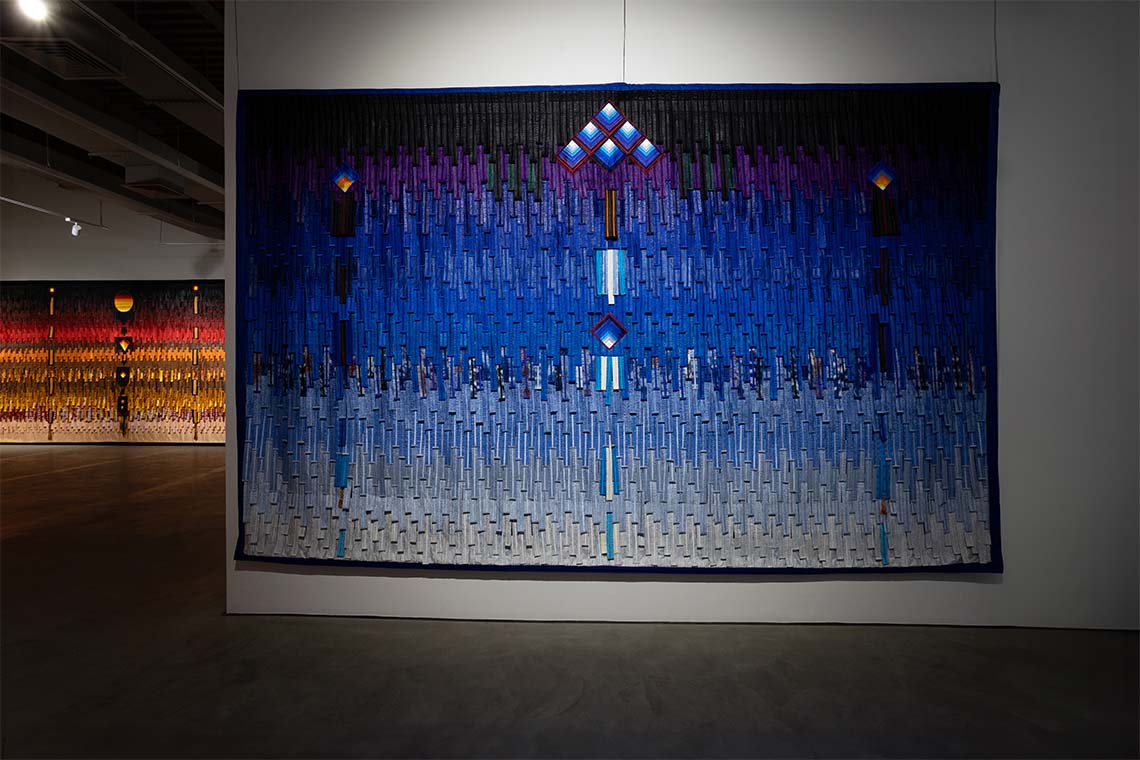

With the titles laying out their provenance, Konaté incorporates Middle Eastern patterns and designs into the layered woven and dyed cloth. Source de lumière (Soleil) Motif d’Arabie sur Fond Ocre (2024) and the smaller Motifs d’Arabie sur fond de gris (2024), for instance, feature the distinctive geometric patterns of the traditional Bedouin weaving technique al sadu; his Maghreb motif sur fond bleu (2024) is crowned by a square diamond with a kaleidoscopic pattern reminiscent of North African tiling; and Tombouctou-motifs (2023) includes three motifs inspired by fabrics from Timbuktu in Mali, often worn by elites. Motif Touareg sur fond bleu du Sahel et du Sahara (2024) features a design characteristic of the traditionally nomadic Tuareg people, who span the diverse geographies of countries including Mali and Niger, as well as Algeria. “When you look at certain patterns, you can see the historical connections between these various regions. Both have developed similar techniques in weaving and dyeing, and there is a shared use of materials like cotton and wool,” Konaté says of the works in Sambadio. “The colour treatment and weaving styles have so much in common, reflecting the interactions between these civilisations throughout history.”

Tombouctou- motifs. 2023 (right). Textile. 400 cm x 261 cm. Image courtesy of Efie Gallery and Moz Photography

Colours are essential elements in Konaté’s compositions; in his largely abstract tableaux – with a semi-figurative exception being the sun that hangs over Source de lumière (Soleil) Motif d’Arabie sur Fond Ocre (2024) – it is colour that communicates. “The colours are not just aesthetic – they carry symbolic meanings related to the environment and the cycles of life,” the artist tells me. In Sambadio, Konaté focuses on “earthy tones”, echoing the land revered in the eponymous song, with the yellow, brown and red hues of Source de lumière (Soleil) Motif d’Arabie sur Fond Ocre (2024) recalling the evolving colours of the desert in the changing light. The artist explains that, for him, blue shades “represent the night”, with his colour sequences “meant to evoke the transitions between the day, twilight and night”. Motifs d’Arabie sur fond de gris (2024) and Motif Touareg sur fond bleu du Sahel et du Sahara (2024) are particularly notable for their subtle gradients of coloured ribbons, which move from black and dark blue, respectively, to pale grey. Certain colours carry distinct cultural meaning, with the gamut of blues seen in Motif Touareg sur fond bleu du Sahel et du Sahara (2024) a poignant tribute to a group known as the “blue men of the Sahara”.

Image courtesy of Efie Gallery and Moz Photography

Sambadio invites viewers to consider the possibilities of textile art as both a medium of expression and a vehicle for cultural exchange. Konaté not only elevates the craft to the level of fine art but, in his marriage of traditional techniques from Mali and the Middle East, also creates a dialogue between cultures, histories and creative practices. This dialogue, as the artist hopes, allows viewers in Dubai to “recognise these shared cultural elements, as they continue to influence both regions today”. His monumental works are no mere decoration – at times they even blur the boundary between art and architecture. Remembering as I walk around the gallery that they were crafted by hand, it strikes me that these tableaux really do reflect the message of resilience and dedication that Konaté finds so powerful in Ali Farka Touré’s song – an embodiment of patience in an era of immediacy, and a testament to the handmade in a world of screens.