The latest group exhibition at Ab-Anbar sees spectral forms take shape, navigating the question of what remains in the eternal interaction of human and landscape.

A painting by Lebanese artist Akram Zaatari depicting a lemon tree above and below ground, its roots encircling a buried artefact, sets the tone for Ab-Anbar’s latest exhibition, Figure–Ground, co-curated by Zeynep Koksal and Azadeh Zaferani. The normally light-filled ground floor of the gallery is shrouded in curtains, obscuring the street view. As in Zaatari’s painting, the world has been flipped inside out, as one enters a space that light does not reach, echoing the dark places where the roots of the lemon tree lie.

Figure–Ground, at its core, invites us to consider how figures exist in landscapes, how they react to their surroundings and leave tangible or sometimes ghostly traces. I am immediately drawn to a large projection of a somewhat pixelated photograph of a cloud of smoke emanating from what appears to be the bombing of an urban area. This image is all too familiar. Indeed, I Will Not Find This Image Beautiful is a snapshot from an Israeli bombing of Gaza in 2014. The artist, Omar Mismar, intervenes in this image of destruction by inputting the names of the victims of the attack into the image’s script code. This causes the ‘ground’ in the image to progressively become obscured by image blips until the entire cloudy smoke trail has vanished under the weight of the distortion.

Photography by Amin Yousefi. Image courtesy of Ab-Anbar Gallery

The artist remains present only in the movement of the cursor as it travels across the screen recording. On the opposite side of the long ground floor of Ab-Anbar, a second work by Mismar echoes this ghostly presence. Figures appear in a static video in the form of young men, collaged onto the ruins and rubble of buildings in Gaza. The men are caught, suspended in time in active stances, as if participating in a form of parkour in their obliterated surroundings. Like in I Will Not Find This Image Beautiful, the human presence reclaims its surroundings, physically imposing itself on the landscape. There is something distinctly male in the action of the young men, a desire to overcome adversity by physically acting on their surroundings. Yet amidst the violence of the image an element of tenderness seeps through. The cursor, still present, caresses the bodies of the young men, as though to comfort them or to remind us, the disembodied artist and the men themselves, that they do and have existed.

The tension between corporeality and incorporeality recurs throughout the exhibition. Almost opposite Mismar’s initial video work, Iranian artist Babak Kazemi draws upon his upbringing in a war-torn region of southwestern Iran in Khorramshahr, number by number (2005). A series of tens of house number plates – recovered from the wrecks of homes following the war between Iran and Iraq – transform before our eyes to reveal the spectral outlines of figures, photos screenprinted onto these tangible remains of human presence.

Photography by Amin Yousefi. Image courtesy of Ab-Anbar Gallery

In every corner of the ground floor, we are confronted with ghosts, whether in suggested human figures as in Pio Abad’s etched hand on marble reaching out in Why don’t you put me in your pocket so that my blood will be mixed with the water at the bottom of the boat, and so that, perchance, I may be lost with you at sea (2025), or in decaying and exploited landscapes. There is something hushed about the display, a sort of eerie silence occasionally punctuated by the click of a projector switching between images in another of Kazemi’s artworks, Report to d’Arcy (2003–11). Haunted by the near presence of things, we are brought face to face with a real spectre in Sherko Abbas’s installation, The Blind Sun (2025–). A traditional Kurdish gown hovers in front of a printed mountainous backdrop, its owner not of the physical realm but still very much present. Next to it, seven photographs of child witnesses of war from Kurdish villages are displayed, each with a twisted lead formation affixed above their image. These, I am informed by Koksal, echo an old tradition whereby the shape assumed by lead when it is dropped into water was used to shed light on the cause of children’s fears. Here, these lead pieces act almost as amulets, protecting those vulnerable to the effects of war and signalling a wish for protection.

What remains once landscapes, people and possessions are destroyed? Only traces, blurred by the passage of time as in the decaying image of Bodybuilders Printed From A Damaged Negative Showing Mahmoud El Dimassy Holding Fadl Kobeissy In Saida, 1948 (2011) by Akram Zaatari, the barren landscapes from a bird’s eye view of human interventions in the desert in Jananne Al-Ani’s video stills from Shadow Sites II (2011), or even Saba Khan’s landscapes of disappearing glaciers in Cosmic Rays Showering on Rocks (2023).

A soothing melody beckons us to the basement, where the question of what remains is addressed in a tightly curated selection of work that strikes at the core of Figure–Ground. We are reminded that it is possessions that are left behind once we are gone. In another work by Zaatari, three lovers progressively disrobe, facing each other in an entirely white setting, a type of purgatory, and undressing until they disappear and all that remains is a pile of neatly folded clothes on the ground. Memories also linger, as in the blurred portraits by Y Z Kami, whose depictions of anonymous young men surround us on the walls, almost all the more present in the absence of a clear rendition of their faces.

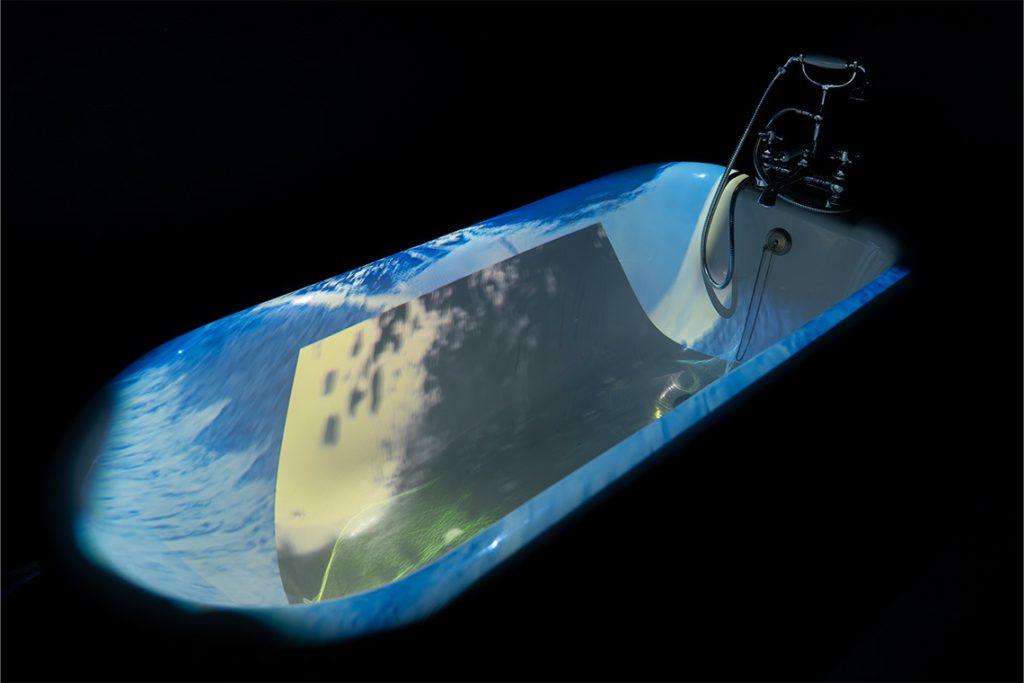

The source of the enticing music is revealed as a minuscule room at the back of the exhibition, housing a video installation work by Palestinian artist Dima Srouji. The room, just large enough to fit the Victorian-style bathtub upon which a video is projected on a loop, is pitch black save for the video light reflecting out of the darkness. The music persists, at once rousing yet melancholic. A Crack in the Water Followed by Return (2024)appears to answer what to do once we are no longer present, when we are no longer figures in or on the ground. Archival footage of the Nakba is reversed and overlaid on film of a dam breaking, in a deeply poignant and hopeful piece which speaks to the possibility of return to a land which has been left, a place where the figures and the ground are inextricable from one another. Figure–Ground followed me home, the tune from Srouji’s work playing on a loop in my head, a haunting melody which evokes both loss and hope. Amid destruction and disappearance, it seems that for the artists in the exhibition the ghosts of things live on. Ultimately, it is up to us to fight against disappearance and bring into the light what others would have banished.