space of togetherness by NEON in Athens explores the work of artists who engage with past histories and contemporary prejudices in the interests of a fairer future.

Just off Pireos Street – the long, busy road that links central Athens to the port of Piraeus – I am sitting in a leafy courtyard. Around me, nervous young people sip freddo espressos and run lines. This is the Drama School of the National Theatre of Greece, home both to auditioning would-be students and (temporarily) to contemporary culture non-profit NEON’s space of togetherness: a show spotlighting the stories that emerge at the crossroads of race, politics and rights.

The exhibition’s curator and NEON’s Director, Elina Kountouri, sits across from me at a long table, the most striking feature of this tranquil space. What might at first glance look simply like a piece of impressive al fresco furniture is, in fact, a new work by Athens-based artist Kostas Roussakis. The table stretches 27 metres and is set with 90 stools, each bearing a letter which, when read consecutively, form four lines of a poem by Greek modernist poet Nikos Karouzos. Entitled Hell, a name drawn from the poem, the table serves as an emblem of the show writ large: a meeting place where people can gather, to share and to listen, but also a catalyst for movement. “In order to read [the poem], you really have to focus. You need to move as well,” Kountouri says.

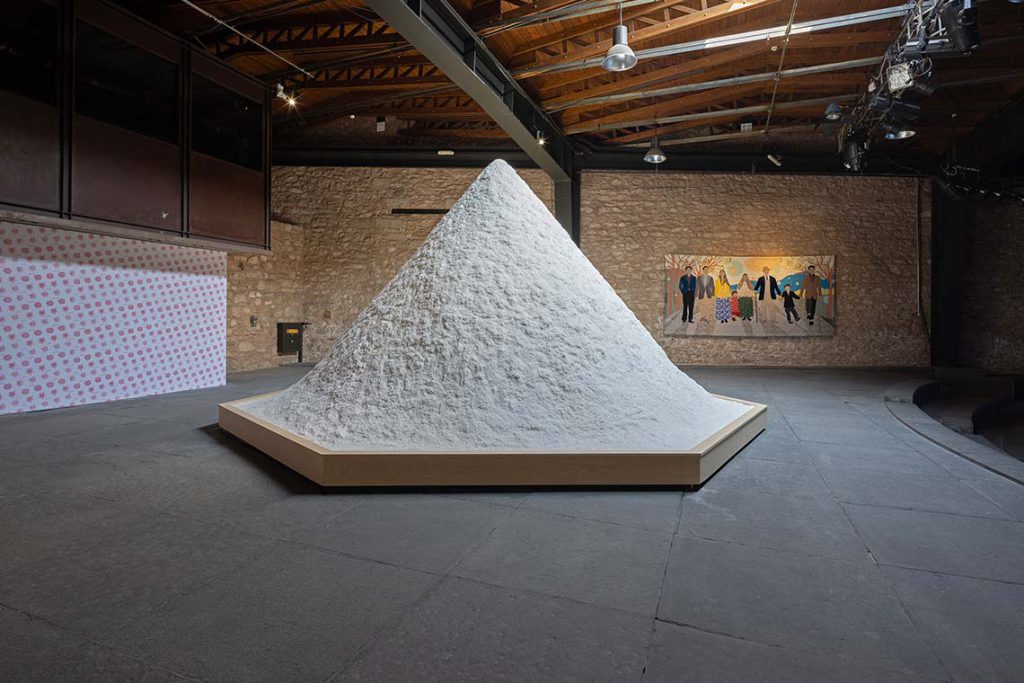

patricia kaersenhout. The Soul of Salt. 2016/2025. Image courtesy of the artists. Małgorzata Mirga-Tas. Maria’s Romani Family. 2022. Image courtesy the artist and Frith Street Gallery, London, Foksal Gallery Foundation, Warsaw and Karma International, Zurich.

Installation view of space of togetherness at NEON at the National Theatre of Greece Drama School | School of Athens – Irene Papas. Photography © Natalia Tsoukala. Image courtesy of NEON

Space of togetherness features 20 artists and collectives drawn from 13 countries and many disciplines, ranging from Polish artist Małgorzata Mirga-Tas’s fabric collages drawing on her Roma ancestry to Soul of Salt (2016-ongoing), the tribute to the enslaved people of the African diaspora by Afro-Dutch artist and activist of Surinamese descent Patricia Kaersenhout. A purposeful choice by Kountouri, the show features only living artists, who seek to re-examine historical narratives, take stock of the injustices of the present, and re-imagine a possible future marked not only by coexistence, but belonging. Among these are several Middle Eastern artists, in whose works particularly Kountouri sees the “weight of history [and a] unique sense of imagining the future”.

In bringing the diverse works together with the activities of the Drama School, combined with a dynamic public programme (including regular, presumably rather lively, school visits), the venue comes to echo what Kountouri calls a “space of flows”: a place shaped and animated by movement and cultural interaction, much as Europe – and indeed the world – is shaped by migration and exchange. This is not, however, a show about “whether we want borders or no borders,” Kountouri says. It is about the human condition and “caring for each other”.

Part of this care lies in recognising and contemplating present injustices. Known for her highly political practice, British-Palestinian artist Mona Hatoum here presents two works that defamiliarise commonplace objects in ways that are unsettling and revealing of systems of control, fear and discrimination in society. In Doormat II (2000-01), Hatoum presents what looks at first glance to be a normal doormat, emblazoned with the word “WELCOME”, but which is, on closer inspection, spiky to the point of causing harm to anyone heeding that invitation. What is ordinarily a feature of domestic comfort therefore becomes an instrument of hostility. Her other work, Baluchi (red) (2007), is a world map in the form of a rug, made unfamiliar by two key features: the map is recessed, with the forms of land masses rendered by absence and it uses the Peters Projection, which presents continents in their true proportion to one another, the alien quality of which lays bare the colonial biases inherent in many representations of the world.

Another area in which such bias might shape our understanding of the world is media – a theme taken up by Palestinian artist Taysir Batniji in his Delayed Reality (2015-ongoing).

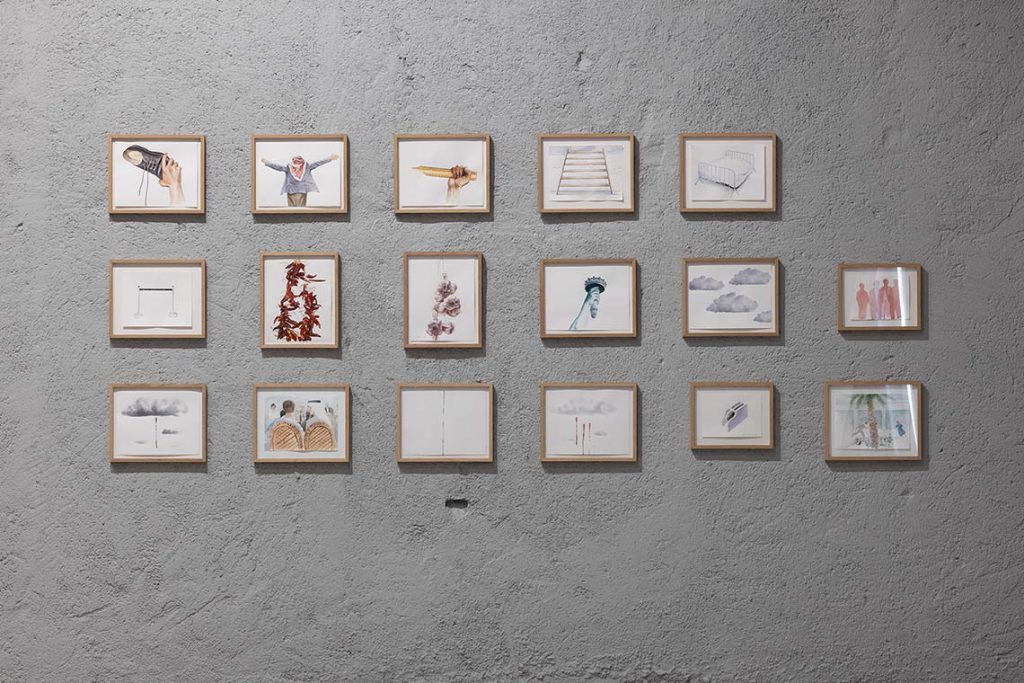

“I have always been fascinated by the way in which the mainstream media, through words, but especially images, try to construct narratives and shape opinions,” Batniji, who started the project following the 2015 Paris terrorist attacks, explains to me. His subjects – depicted using pencil and watercolour, and drawn from media representations – include a wreath of dried chilies, a man with outstretched arms wearing a keffiyeh, and a hand brandishing a shoe. Divorced from their wider context and transformed (by a close-up view, for instance), Batniji’s images gently interrogate the murky territory between reality and representation. “What I attempt in my work is to deconstruct these narratives, to question them or to propose another reading of events and history,” he explains.

In her new commission Restor(y)ing Waters (2024), Cypriot artist Marianna Christofides also addresses the theme of representation via a “process of unearthing buried or bypassed stories” – and invites visitors to tune in. The seven-channel sound installation – encompassing a hanging sculptural braid formed of discarded electrical wires, around which visitors walk or stand as they listen – intertwines the testimonies of women associated with the Melissa Network, a non-profit for migrant women in Athens, with vocals by Greek singer Savina Yannatou and composer Stavros Gasparatos. The women’s narratives take water as a starting point that both “connects all bodies” and inevitably “conveys stories of exchange and confrontation,” with their testimonies speaking to broader themes of freedom, exploitation, justice and dreams. “I try to expand ways of being together, sharing, listening and perceiving […] enabling ‘ecosystems of exchange’ to emerge,” Christofides says of the shared listening space created by the work.

Rivers, Banks. 2019.

Installation view of space of togetherness at NEON at the National Theatre of Greece Drama School | School of Athens – Irene Papas. Photography © Natalia Tsoukala. Image courtesy of the artist/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn, 2024 and NEON © Marianna Christofides

If Restor(y)ing Waters is about listening, Døcumatism’s ongoing community project about the African Diaspora in Greece – the Afro-Greeks – is about fostering a conversation. This collective of creatives, historians, educators, researchers and social workers in Athens’s multicultural, densely populated Kypseli neighbourhood strives to make the ‘invisible’ – namely the margins of Greek society – visible.

The wide-reaching project, which encompasses video, interviews, research, public actions and an archive, is introduced to audiences at space of togetherness via a number of videos. These include a particularly powerful series of interviews with members of the African Diaspora, in which it seems that the subject is looking at and speaking directly to the viewer, and a video diptych that juxtaposes years of protest (against austerity, for example) in the Greek capital, with the artistic interventions of the Afro-Greek community against prejudice and racism.

The focus on video, filmmaker Menelaos Karamanghiolis tells me, is so that the group’s public actions “can become part of the archive”. This rich collection of materials – from tomes of history and anthropology detailing the arrival of Africans in Crete under the Ottoman Empire (a historical reality unknown to many Greeks) to schoolchildren’s paintings reimagining the iconic “evzones” soldiers as Afro-Greeks – finds its home in a room of the drama school for the duration of the exhibition, with members of the collective on hand to chat. “It answers your questions, but also brings up questions – actually starting a conversation,” Grace Chimela Eze Nwoke, Greek anthropologist and performer of Nigerian descent, says of presenting the project’s (ever-growing) findings. “The questions are no longer about whether the community exists. They’re about what kind of prejudice [viewers] might have had, why they didn’t know anything about the community, and what Greece is actually doing about these issues.”

For Moroccan-French artist Bouchra Khalili, the conversation cannot only be with contemporary peers, but also with our forebears. “In order to be able to contemplate a potential future, I invite viewers to start with looking at the unachieved promises of the past,” she says. The exhibition brings together Khalili’s mixed-media installation The Circle (2023) and film The Storytellers (2023) which draw on her research on the Arab Workers’ Movement and its theatre groups, Al Assifa and Al Halaka. These stand alongside the poster A Timeline for a Constellation (2023), which sets out a chronology of the movement and details how theatre was central to the group’s activism. With the complex narrative structure of the video works forming a dialogue between disparate times and geographies, and the timeline resembling a constellation of connections and actions of solidarity rather than a linear chronology, Bouchra underlines that, although these works centre on a certain historical movement, they “address a timeless human need in that, how do we form communities of equals in rights and dignity?”

As much as space of togetherness is a reflection on the human condition, the show’s discussion has, necessarily, a profoundly political dimension – even, and perhaps especially, when the stories told are personal. “This whole project is also a political statement. When we’re sharing stories we’re also always, on some level, talking about the legal system and migration policy,” Nwoke says of the Afro-Greeks, for instance. In its laying bare of the prejudices that pervade contemporary society, the exhibition posits that imagining new ways of belonging requires interrogating and unpicking the socio-political structures of today to make way for a new solidarity – and that this is a process in which artists can play a vital role.