Uzbekistan’s debut biennial brings new lustre to the historic city of Bukhara, where partnerships between contemporary artists and master artisans challenge traditional stereotypes of authorship and attribution.

It’s a name rich in resonances from the past – Bukhara, fabled city on the Silk Road, a cosmopolitan entrepôt where merchants traded their luxury wares and intellectuals gathered in coffee shops to discuss astronomy, science and literature. The result of all the wealth and cultural interchange was a diverse society and an outstanding architectural heritage, a skyline bedecked with shimmering domes, madrasas, mosques and fortresses whose beauty and sophistication were the talking point of salons in Europe and beyond.

Fast forward several centuries and what do we have now? I first visited Bukhara as a postgraduate student in 1994, when Uzbekistan had only recently disentangled itself from the collapsing Soviet Union and the atmosphere still felt raw and somehow uncertain. While the new country was finding its feet, its cultural heritage endured as the bedrock on which Uzbek society – both ancient and modern – was grounded. I recall seeing craftsmen working on rugs and ceramics in the same way as their fathers and grandfathers before them, and myriad traditional mudbrick buildings sporting the famous blue tiles, even if some were rather worn and chipped.

Now a flagship UNESCO World Heritage Site, and with many of its flagship historic monuments restored, for the most part sensitively and with respect, Bukhara is at a new crossroads. Forget the erstwhile Silk Road. New connectivities and thoroughfares are now opening up, both creatively and economically. “We see culture and economic growth as moving forward hand-in-hand”, says Gayane Umerova, chairperson of the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation and the commissioner of the city’s inaugural biennial, which opened earlier this month. “The Bukhara Biennial is a centrepiece of our wider programme to expand access to art and strengthen the already strong connection in Uzbekistan between heritage and contemporary creativity.”

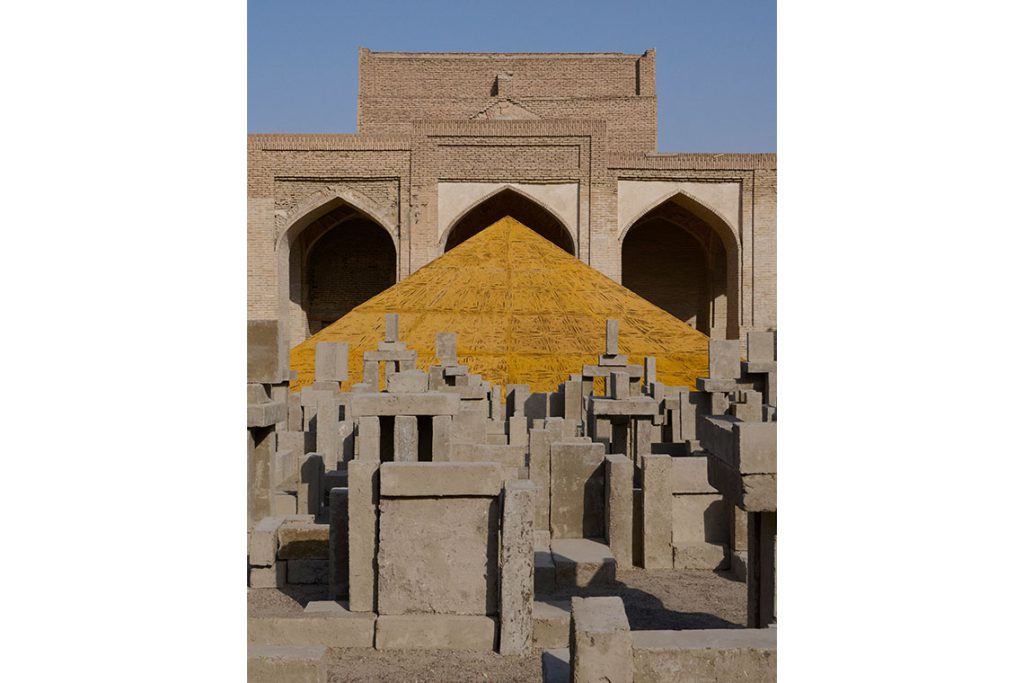

Longing, 2024–2025. Photography by Felix Odell. Image courtesy of the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation

The biennial is taking place in the heart of historic Bukhara, where a conservation and revitalisation project has seen a raft of interventions designed to upgrade local infrastructure in ways that are both sympathetic to their context and sustainable. They are also integral to the repositioning of the city as a permanent hub for contemporary art. “Art as a medium is very important in Bukhara,” says Wael Al Awar, the biennial’s creative director of architecture. “The biennial is bringing back the very important dialogues that happened here historically and which are necessary to have again. But for a 10-week event, it’s also important that you don’t just come and then leave. We need to look ahead in terms of what we must build for the people of Bukhara that’s longer term, more sustainable and more visionary.”

Given the rash of biennials that have strafed – or limped, in some cases – their way across so many cities worldwide in recent years, one might be forgiven for a sense of ennui at the prospect of more. Yet in Bukhara any such qualms are rapidly and comprehensively dispelled. The biennial opened at a time of ferocious heat, of an intensity that if nothing else served to underline the red-hot character of what was going on. For here is a biennial that is not grafted on to its environment, as so many have been, but firmly derived from it.

Central to the biennial’s ethos is the concept of cross-disciplinary partnerships, with all of the 70-plus site-specific works the result of collaborations between artists – both international and Uzbek – and local artisans. It is an approach masterminded by artistic director Diana Campbell, who is well-versed in finessing the synthesis between craft and contemporary art from her work on the outstanding Dhaka Art Summit and beyond to create dramatic and thought-provoking new expressions. Immediate standouts are that every work in the biennial was produced in Uzbekistan, a reflection of the depth and breadth of local creativities, and that the artists and their partnered master artisans are given equal billing in an exercise in elevation. “Craft in Uzbekistan is unlike anything I’d seen previously,” says Campbell. “The biennial is a cross section of craft traditions and presents a different way of thinking about the dialectic between the thinker and the maker.”

I found the biennial theme – Recipes for Broken Hearts – initially confusing. But once explained – it is drawn from a local legend that credits Ibn Sina, Bukhara’s famous son, with the invention of plov, Uzbekistan’s national rice dish, to heal the broken heart of a prince who was prevented from marrying a craftsman’s daughter – it seemed to chime well with what I saw presented around me. The biennial weaves a story of parallels and synergies on various levels, not least of art and food providing comfort and balm, dual means of healing that might offer hope in a depressingly fractious and disjointed world. Offering spiritual and physical sustenance may seem an easy hit, but here it is done elegantly and with imagination.

The food theme is well integrated across the biennial and sustained by culinary activations led by Uzbek and international chefs. I particularly enjoyed the Brutalist Bukhara menu devised by Carsten Höller, which exhorts diners “to taste Uzbekistan brutalistically”. Each pared-back course is based on traditional Uzbek cuisine but comprises only one ingredient (plus water and salt) – – think three different ways of pumpkin and a “melon moment” inspired by the Slavs and Tatars/Abdullo Narzullaev biennial installation Quords & Qurban. Lean and mean, the menu provides an innovative take on Campbell’s wider curatorial message of food as a dial-up for memory, storytelling and senses of togetherness.

Created by artists from 39 countries and ranging from large-scale installations and sculptures to small clay whistles (of which more below), the biennial’s artworks are presented across five venues: two madrasas, a caravanserai, the Khoja Kalon complex (Bukhara’s most iconic site, with a mosque and eleventh-century minaret, madrasa and traditional water tank or hawz) and the public spaces and covered bazaars that were the community heart of old Bukhara. There are no purpose-built pavilions or temporary structures. Instead, the works are integrated into existing spaces and designed to resonate with the architectural rhythm of the city.

An immediate thread to follow is the monumental ikat work Longing, by the collective Hylozoic/Desires, comprising Himali Singh Soin and David Tappeser Soin. Created in collaboration with fifth-generation ikat master Rasuljon Mirzaahmedov, bolts of the decorated textile are strung in a loom-like fashion along and over the Shah Rud, the historic canal that bisects the historic centre. Their algae-like pastel patterns – inspired by satellite imagery of the now withered and moribund Aral Sea – pay homage to the once-vast and heart-shaped lake which historically for many Uzbeks was their only concept of the ocean. In conjunction is The Rising of the Full Moon, a performance piece by Hylozoic/Desires in collaboration with drummers and karnai (a traditional form of trumpet) musicians of Bukhara that takes place every full moon during the biennial to summon replenishing water from the sky.

Central to Uzbek identity, textile craftsmanship is deeply embedded throughout the biennial and is nowhere more dramatic than with Gulnur Mukazhanova’s The Healing of Present, a collaboration with ikat weavers from the Margilan Crafts Development Centre. Dressing the entire façade of the Rashid Madrasa, it is the glittering conclusion of Mukazhanova’s exploration of new custom designs that complement a vast archive of vintage textiles.

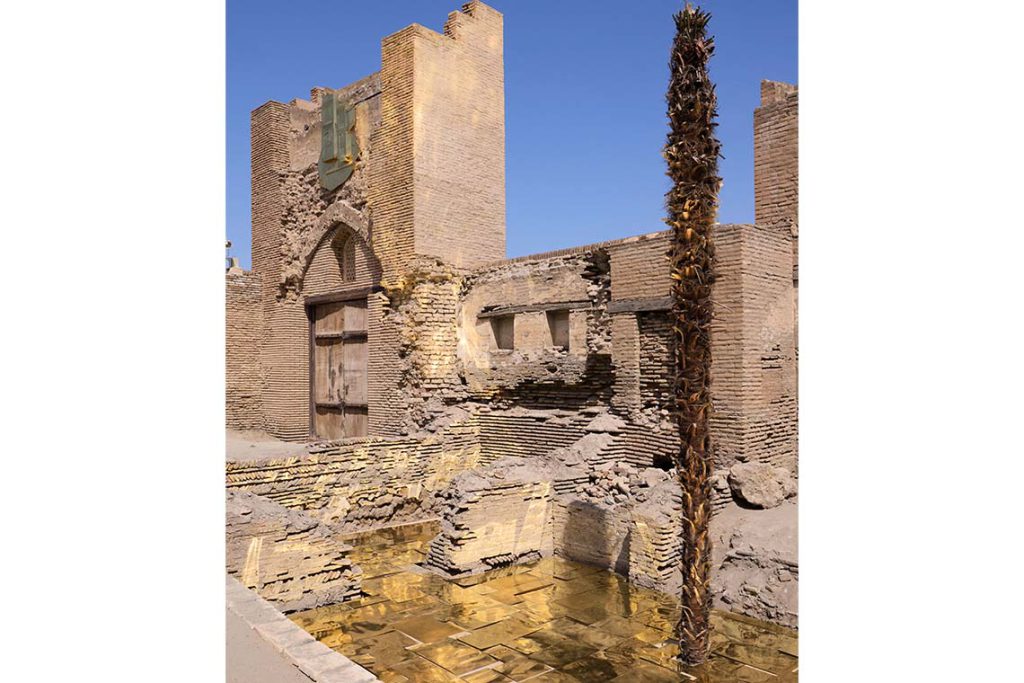

Image courtesy of the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation

Other textile highlights include Jordanian artist Samah Hijawi’s vast mural work Kinships and Cosmologies, displayed in the Caravanserai and on which she worked with Uzbek embroiderer Ahmad Arabov and his team. Presenting a map of scientific, spiritual and edible connections that reflect Uzbekistan’s history of agriculture and trade, it seeks to connect Earth with the wider universe in a contemporary interpretation of the ancient concept of ‘as above, so below’. I found it a curiously absorbing piece, not simply in terms of the tactile qualities of its composition but also how it unpacks the transmission of ideas through ingredients, stories and time along age-old routes, both temporal and spiritual.

Almost immediately adjacent are two untitled works by Wael Shawky, created in collaboration with master coppersmith Jurabek Siddikov. Bukhara was once known as the Copper City, and boasts a millennia-long tradition of metalworking. Shawky’s two copper panels, intricately engraved by Siddikov, continue the Egyptian artist’s exploration of alternative histories and identities, here expressed in a style redolent of illuminated manuscripts. Traditionally seen as more than simply a metal, copper has been long revered in Uzbekistan for its perceived properties of healing and positivity, for which it was valued in the making of ritual objects and personal keepsakes. There is certainly something distinctly talismanic about Shawky and Siddikov’s iridescent panels.

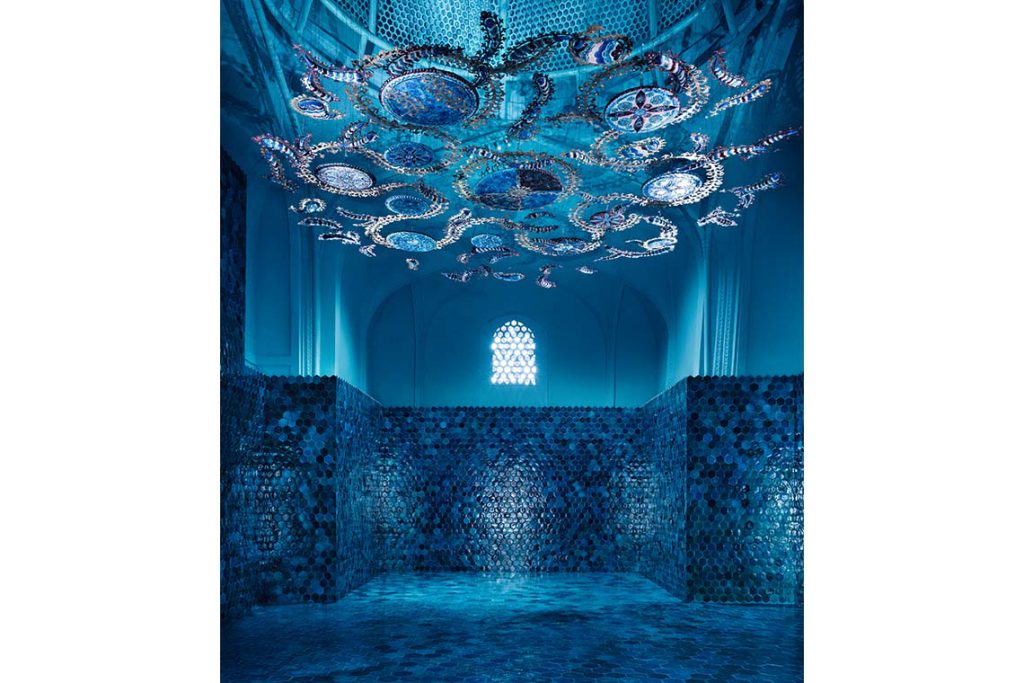

Siddikov also collaborated with ceramic artist Abdulvahid Bukhoriy, on the richly immersive Blue Room in the Gavkushon Madrasa. Drawing on ancient healing rituals in which fish become a vessel for absorbing human illness and frailties, it occupies the madrasa’s former prayer room and proved an instant draw for art aficionados and local people alike. Composed of Bukhoriy’s handcrafted blue wall and floor tiles featuring Uzbek textile motifs such as fish and flowing water, into which Siddikov’s exquisite brass-and-copper chandelier sculpture is suspended from above. It feels like entering a multi-sensory aquarium.

Photography by Felix Odell. Image courtesy of the Uzbekistan Art and Culture Development Foundation

The scale of some of the artworks in the biennial is impressive, perhaps most notably in the ruins of the Khoja Kalon mosque where Antony Gormley worked with Bukharian restorer Temur Jumaev and his team of brick-makers to create CLOSE. A collective endeavour comprising thousands of sculptural mud bricks arranged to form a labyrinth (or temple, I felt) of bodies, it was quickly dubbed “the graveyard” by locals. Walking through and around it is like moving through shadows, stepping over slumbering forms fashioned from a timeless material that could date from centuries ago – or just last week. A few days later I saw a drone view of the whole assemblage and wish that had been more widely available to visitors, as it provided a stunning and very different perspective on one of the biennial’s undisputed highlights.

The sense of collectivity and the value of organic materials engendered in CLOSE are also central to the powerfully participatory Mur-Mur, tucked away in a corner of the Caravanserai. Here, a collaboration between artist David Soin Tappeser, the late legendary ceramicist Kubaro Babaeva and her students, and sound artist Boris Shershenkov has produced a work of great charm and impact. Piled on the floor are hundreds of handcrafted clay whistles or hushtaks, a traditional child’s toy that takes the form of a bird or fantastical creature and was used to usher out winter and ward off evil spirits. Visitors are invited to take one and play it at a collective microphone, where it is recorded and added to an evolving collective soundscape running through the course of the biennial. They are then encouraged to take their whistle home, thereby incorporating it into their lives. One of my enduring memories of my time at the biennial is the sound of children and adults alike piping and whistling their way home – a neat expression of art on the move.

So it is that Bukhara’s first biennial articulates the open movement of people and ideas, delivering what Campbell has called “an event where everyone has a place at the table”. From what could so easily have been an Orientalist pageant has sprung something altogether more innovative and valuable, disarming in its authenticity, honesty and thoughtfulness. Not only is it helping Bukhara – and Uzbekistan more widely – navigate a new identity and role in the sphere of contemporary art, but it is also fuelling synergies and long-overdue parities between creators of art and craft. Dare we hope that biennials may never be the same again?