Across layered photographs, intimate films and textured installations, the latest show at Efie Gallery explores how memory lingers and how healing moves at its own pace.

I stepped into Efie Gallery’s new space beneath a sky far gloomier than Dubai’s usual sun-drenched promise. The title of the show lingered in my mind – time heals, just not quick enough…, a quiet echo that seemed to foreshadow what lay ahead. The space greeted me with stark white walls and the air was still, almost reverent. Curated by Ose Ekore, the group exhibition gathers the voices of five contemporary artists: Samuel Fosso, Aïda Muluneh, Kelani Abass, Abeer Sultan and Sumayah Fallatah.

At first, I was intrigued by the black-and-white photographs, lined up almost like a wall of fame, each one radiating a distinct personality. These are part of Samuel Fosso’s early series 70’s Lifestyle (1974–78), marking the artist’s first major exploration of photography beyond the borders of the Central African Republic, where he was mostly based. This body of work captures a young Fosso experimenting with identity and style in front of the camera, using self-portraiture as both a personal and political act. He channels the flair and confidence of African American culture, which he first encountered through magazines brought by American Peace Corps volunteers visiting the region.

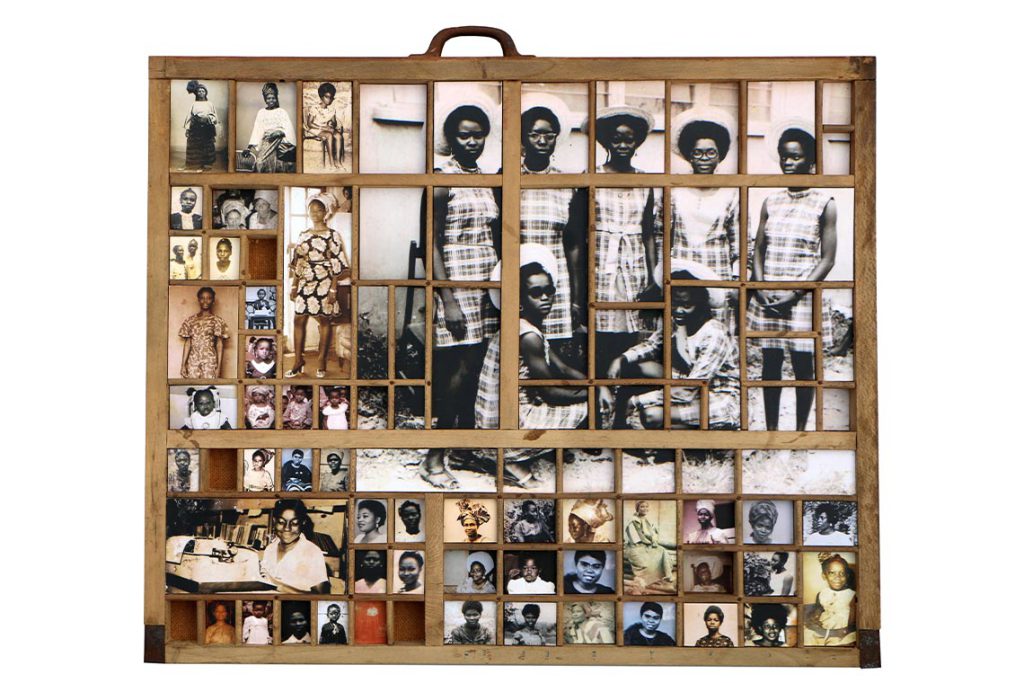

Kelani Abass’s series Unfolding Layers (2021) sits atop neatly stacked white bricks resting against a raw, unadorned wall, setting the stage for a reflection on ongoing archives, memory and inherited visual culture . In this series, Abass transforms the humble letterpress type case into a grid of memory, each compartment filled not with text but fragments of lived experience. Vintage photographs retrieved from his father’s printing studio, original prints and hand-coloured stand-ins form narratives too layered or fragile to put into words. From a distance, the works resemble a kind of a modern reliquary or perhaps the architecture of a beehive. Each cell holds its own story, but together they form a collective hum. There is a sense that the portraits, although still, are somehow in motion, leaning toward one another, softly tinted in sepia and creating a visual rhythm that feels at once archival and alive.

In similar essence yet different materiality, a stitched composition of family photographs weaves Sumayah Fallath’s personal and family narratives. In I became you, so I lost myself (2024), she layers family photographs, archival images and indigo-dyed textiles. There is something ritualistic in her approach, as connection, as bloodline, with the indigo fabric forming a kind of emotional scaffold and invoking histories when set against her themes of assimilation. The ache is subtle, but persistent. In parallel, Fallatah attempts to replicate the gesture, both physically and emotionally. The result is a quiet conversation between memory and mimicry, between parent and child, past and present. It is the kind of work that breathes with you as you watch it and sighs with you afterwards.

Not far from this reflection, ocean currents seem to ripple. A series of dreamy self-portraits, spliced with images of marine life and imagined cartographies, offers a different perspective of archival recovery, one rooted not in land but in water. In Agua Viva (2024), Abeer Sultan reflects on her family’s migration from West Africa to Saudi Arabia. Collages of corals, jellyfish and shells become poetic placeholders for erased narratives. Her self-portraits are particularly evocative, submerged figures that feel less like bodies and more like spirits between worlds. The line between fact and fiction dissolves, and I found myself left swimming through the myth, memory and speculative futures.

The Gallery of My Shadow’s (2021) presents Aïda Muluneh’s interplay of form and colour. Central to the image are three women draped in striking blue, their figures poised like flowers against the desaturated monochrome forest behind them. Each figure is enveloped in layers of cultural meaning, merging Ethiopian motifs with a contemporary visual language. The work’s bold use of colour draws the eye directly to the women, inviting reflection on themes of identity, shadow and resilience. Rather than overwhelming, the visual clarity sharpens the narratives, allowing Muluneh’s complex dialogue around womanhood and cultural memory to resonate quietly but insistently.

Taken together, these works do not just examine the passing of time; they analyse its emotional residue. Ekore’s curatorial vision lets each piece hold its own space while also contributing to a larger rhythm, a visual cadence that ebbs and flows between grief and grace, silence and spectacle. I headed out into the sun, sunglasses on, the weight of memory still clinging to my shoulders like heat.